Becoming Led Zeppelin Isn’t Trying to Tell the Whole Story

A thoroughly researched documentary blessed by control freaks who still can’t, or won’t, wrestle with the less flattering parts of the band’s history.

Let’s get it out of the way: There are no mud sharks in Becoming Led Zeppelin, Bernard MacMahon and Allison McGourty’s long-awaited and already record-breaking first “authorized” documentary about the band’s early years. There is no sex, drugs, or rock-and-roll excess from the band that invented the cliché. And sorry, no “Stairway to Heaven.” We only go up to Zeppelin’s triumphant January 1970 performance at London’s Royal Albert Hall, just after Led Zeppelin II displaced Abbey Road as the No. 1 album in America — the moment their imperial era officially began.

If we take the three surviving band members at their word — the documentary’s only talking heads, each interviewed separately, alongside snippets of an unearthed interview with the late John Bonham — Led Zeppelin’s story was one of a singular artistic vision, executed by nice, talented English boys who were misunderstood until their fans drowned out the critics. It’s the condensed, PG version of Hammer of the Gods, Stephen Davis’s 1985 biography in which Zeppelin’s infamous tour manager, Richard Cole, mentioned here briefly only in passing, shared many juicy and contentious stories that helped crystallize the most devilish parts of the band’s legacy.

Variations of these devilish details have been well known for decades. In Hammer of the Gods alone, in which even Davis questions some of the rumors relayed to him yet nevertheless printing them, we read about how the band sustained their vigorous touring by drinking vaginal secretions, Jimmy Page’s “prowess” with a whip, “tumescent girls immersed in tubs of warm baked beans before coitus,” and more. There’s the story of Ellen Sander’s more credible and harrowing experience of being assaulted while on tour with the band for a Life feature, a time she described in more detail to Rolling Stone in 2019. Then there’s mud shark, in which members of the band and Cole allegedly pleasured a drunken girl tied to a bed in Seattle’s Edgewater Inn with pieces of a shark while a member of Vanilla Fudge recorded them on Super 8 cameras. And this was just within the early years covered by MacMahon’s documentary.

Becoming Led Zeppelin feels like an antidote to Davis’s tell-all, for better or worse. It’s a thoroughly researched documentary blessed by control freaks who still can’t, or won’t, wrestle with the less flattering parts of the band’s history. It’s a part one without any follow-up.

This does not mean Becoming Led Zeppelin is bad, or even misleading. Some of it was even by design. According to MacMahon, Becoming Led Zeppelin is less an antidote and more a continuation (perhaps even the unofficial fifth part) of his four-part American Epic film series exploring the origins of American popular music, using Led Zeppelin — the ultimate fanboys of those early American blues and rock-and-roll records — to explore postwar ’50s and ’60s music through film footage and photographs unseen by most fans. To MacMahon, focusing on his existing journey through American music history was a purer way to tell Led Zeppelin’s story, more akin to Howard Mylett’s out-of-print 1976 biography that had direct access to the band while everyone was still alive, as opposed to what MacMahon calls “tabloid books” like Hammer of the Gods. He and McGourty did the very un-tabloid duty of interviewing over 175 people as background for the film to corroborate what’s on-screen. “I go and meet [the band’s] childhood friends,” says MacMahon. “I go and track down the priest that made John Paul Jones [his] organist. I go to Glyn Johns myself. I go to Eddie Kramer.”

Much of this background information and archival footage is a treasure for fans. The beginning is especially compelling, with live footage of each member’s earliest musical influences, from English trailblazers Lonnie Donegan and Johnny Kidd to their American counterparts Little Richard and Johnny Burnette. The overall story beats also align with the first chapters of Hammer of the Gods: London session professionals Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones teamed up with mystic Black Country outsiders Robert Plant and John Bonham to shake up an English blues revival that had run its course, with the ambitious studio nerd Page picking up the challenge first presented by underground American FM stations and the then-new Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band to treat the full LP, rather than the pop single, as the true artistic statement. The creation of “Whole Lotta Love,” the film’s climax — which sounds glorious on Imax speakers — was the cultivation of these early years and Led Zeppelin’s first peak, the moment “heavy” entered the guitar lexicon and ended the ’60s for good.

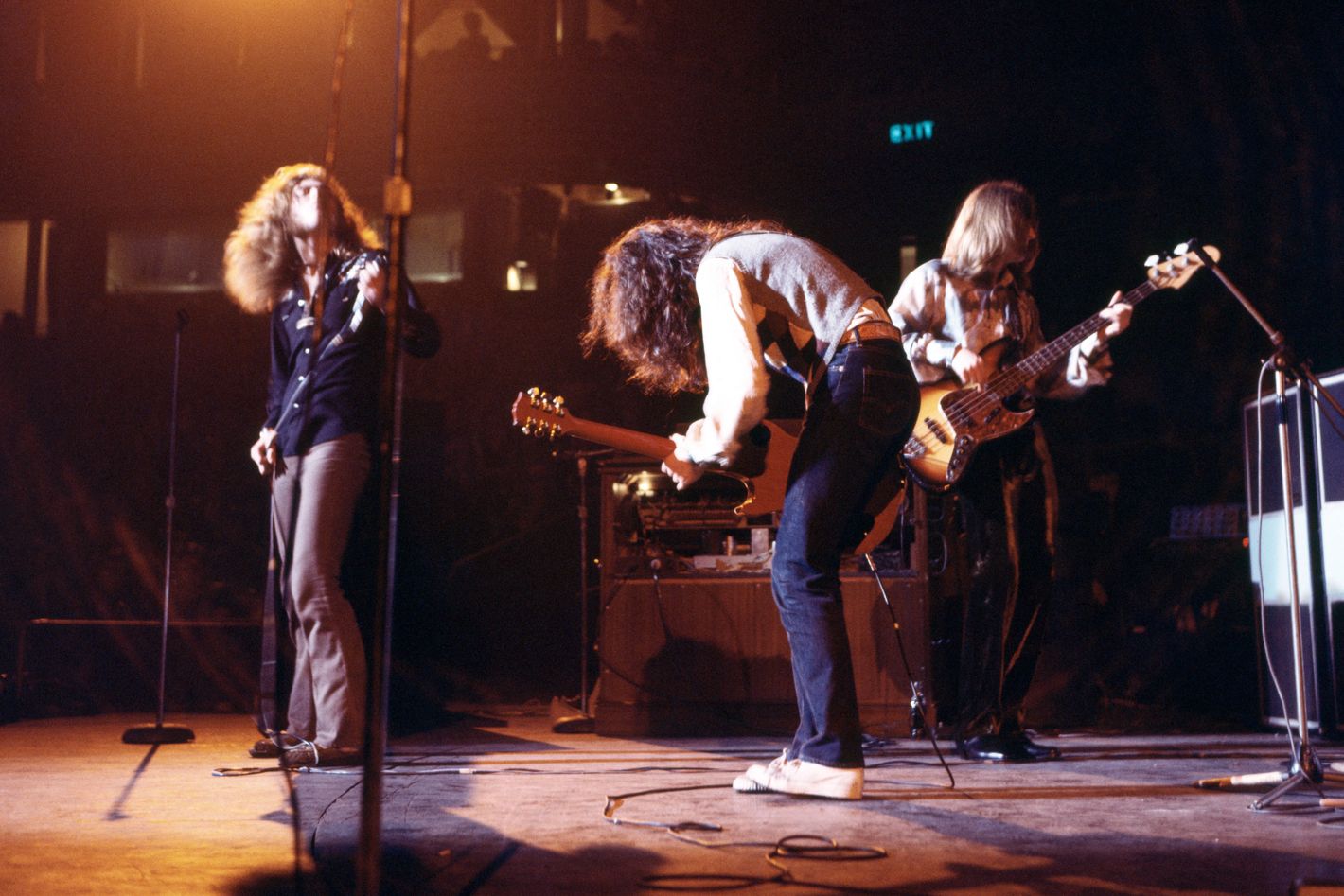

The film also does what no written biography could do: It puts you in the literal room with Led Zeppelin, wisely marking their evolution with several live performances. We watch Zeppelin in real-time evolve from shaggy and confounding noisemakers — the first couple of shows feature several stone-faced audience members plugging their fingers into their ears — into an impossibly confident and tight unit, where the loudness was the point. Some of these concerts, like their 1969 Danmarks Radio performance and the aforementioned 1970 Royal Albert Hall show, have been on YouTube for a while, but they’re far more compelling on Imax.

However, the documentary leaves plenty of non-scandalous details on the cutting-room floor that could have been added to make this the essential Led Zeppelin story. For example, Hammer of the Gods, aside from its gossipy prose, does include many engaging and necessary details on how Page produced and mixed Zeppelin’s earliest classics. (My favorite nugget: Page’s trick of placing additional microphones behind the amplifiers to create more balance and capture the band’s ambiance.) The documentary lets Page nerd out a little toward the end, but casual fans might not walk away believing he was one of rock’s most underrated and influential producers.

Hammer of the Gods also still does a better job of situating Zeppelin within the cultural landscape of 1969 Southern California, Zeppelin’s adopted American home, which at the time was grappling with a rewiring of the American spirit from Nixon becoming president, the escalation of Vietnam, and the Manson killings. “These were witchy times,” wrote Davis in his book’s overture, “Led Zeppelin’s antics were merely the sadistic little games of young English artistes loose in the United States with dirty minds and unlimited resources … but by the cold light of day they were all really quite nice, even gentlemen.” Becoming Led Zeppelin sort of attempts this contextualizing by projecting footage of civil-rights protests soundtracked by “Good Times Bad Times,” implying, unconvincingly, that Zeppelin was responding to modern concerns rather than just mining mythical energy from their heads. It’s clear that MacMahon is so set on telling one specific story of Led Zeppelin that he avoids all the stories that make up the whole picture of a complex legacy.

These omissions and caveats shouldn’t deter fans or curious newcomers. I strongly recommend not waiting until VOD to experience in theaters what may be the best that Led Zeppelin has ever sounded on film. It’s a snapshot of one of rock’s best bands coming into its own that feels just as compelling with your eyes closed. But don’t expect Becoming Led Zeppelin to displace Hammer of the Gods as the definitive Led Zeppelin text.

Related