Caspar David Friedrich’s Lonely Islands

A retrospective at the Met captures the German romanticist’s epic melancholy.

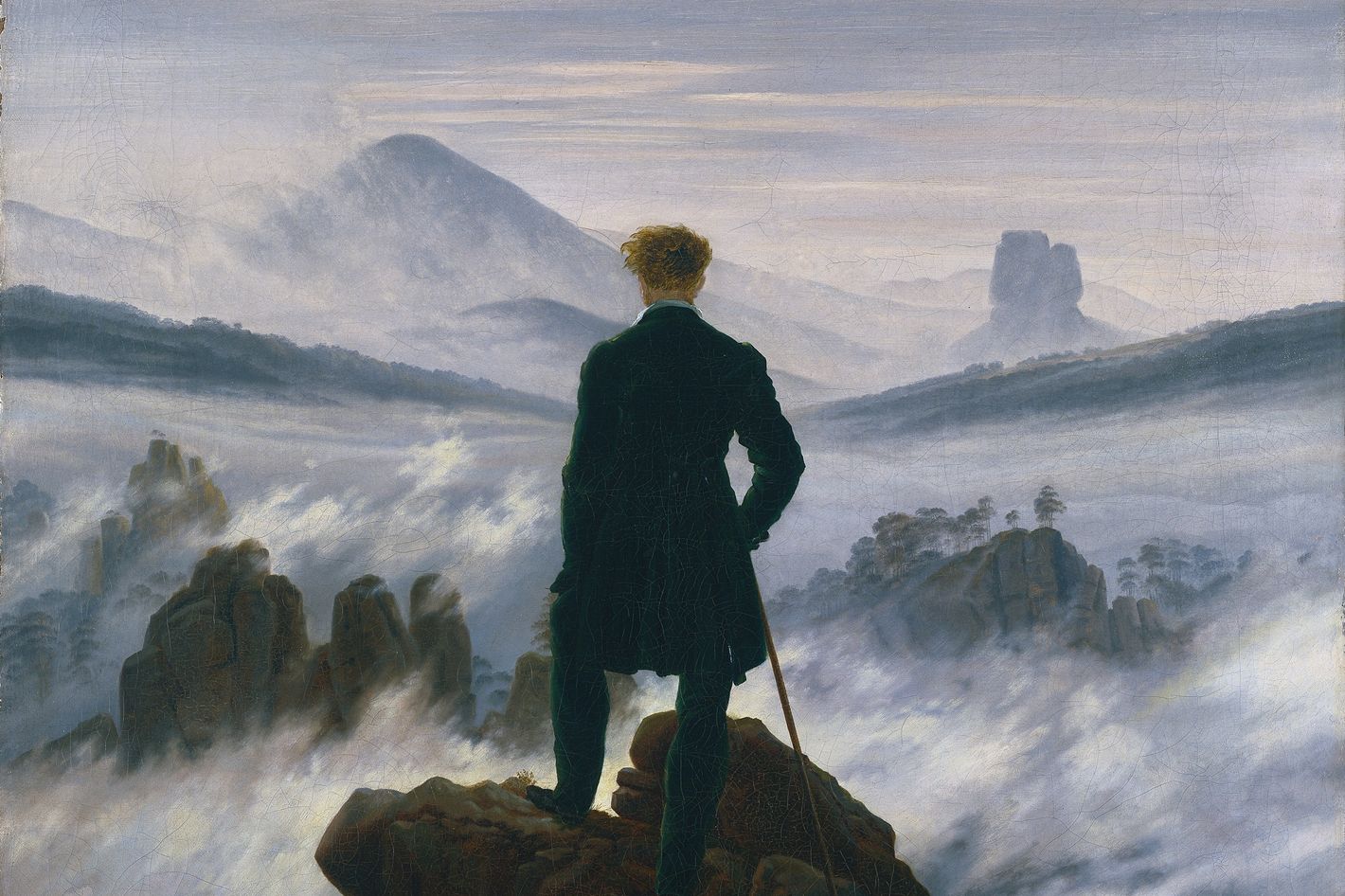

You know the work of Caspar David Friedrich even if you don’t think you do. His classical landscapes, brooded over by solitary individuals or small groups, have adorned metal albums, book covers, and dorm-room posters. His art helped inform the dreamy imagery of Disney’s Fantasia, and Samuel Beckett said Friedrich’s moody Two Men Contemplating the Moon inspired Waiting for Godot. The influence of the 1817 existential masterpiece Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog — which depicts a man in a dark overcoat with cane poised above a cloud-wreathed valley, both master of his domain and utterly alienated from it — can be seen in everything from the poetry of Edgar Allan Poe to the television show Severance to countless memes. Friedrich is the painter par excellence of German Romanticism yet also a man for all times and places.

“The Soul of Nature,” the Met’s new retrospective of nearly 40 of Friedrich’s paintings and more than 30 of his drawings, marks the 250th year since the artist’s birth in 1774. Much of Friedrich’s work is housed in Europe, so this is a rare opportunity to assess him in full. His pictures of graveyards, seashores, shipwrecks, and mountain vistas force us to ponder our place in the universe. No one does anything in these paintings except turn their back on the viewer and stare forlornly at the world in all its sublime majesty, which Friedrich suggests is a mirror for the world within. “Close your bodily eye, so that you may see your picture first with your spiritual eye,” he once wrote.

What might the spirit’s eye behold in these pictures now? Friedrich’s subjects appear disaffected, melancholy, and beset by torpor as they gaze on landscapes that awe and confuse in equal measure. They are at the end of a world broken by fate, their turning inward all too relatable.

The artist spent most of his life in Dresden. He knew early success, his dazzling sketches showing Van Eyck levels of graphic control. He hails from a period rich in great artists. These include visionaries Goya and Blake; giants of proto-modernism like Constable, Ingres, and Delacroix; and the showoff Turner. But Friedrich forms a singular art-historical branch, leading to the death-haunted Munch, the low-affect surfaces of Magritte, and much iffy illustration.

He drew outdoors but painted in his studio from memory and imagination. One of Georg Friedrich Kersting’s portraits of the artist, 1811’s Caspar David Friedrich in His Studio, gives us Friedrich alone, seated at an easel, rendering a waterfall on the canvas. “I must remain alone and know that I am alone,” Friedrich maintained, “in order to fully see and feel nature.” At 44, he married a woman 19 years his junior, with whom he had three children. He died in 1840, forgotten, out of style, in financial straits. The Nazis, unfortunately, saw in Friedrich’s expansive landscapes images of Aryan “living space.” He was discredited, only to be rediscovered in the late 1970s.

Friedrich came of age during the early Romantic period, influenced by neoclassicism. All this was swept aside by the French Revolution, the Reign of Terror, and the Napoleonic Wars that followed. Europe emerged exhausted after Waterloo in 1815. Friedrich once referred to “the darkness of the future”—this is the pessimism that dominates his art and his epoch.

The 1808–10 painting Monk by the Sea, featured in its own alcove at the Met, is a superlative example of Friedrich’s dour romanticism. There is a very low horizon — one of the hallmarks of his work. We see a sliver of earth; above that, black, choppy water forms a narrow middle ground; the rest of the painting is sky. (It is no wonder that many have commented on Friedrich’s influence on Rothko.) A lone, windblown monk stands on the shore, staring into the abyss. The Abbey in the Oakwood is similarly enigmatic, featuring a derelict cemetery with tilting tombstones and the ruins of a church amid leafless trees, as is Greifswald in Moonlight, a nighttime scene of fishing vessels at low tide with a German city in the haze. It is possible to glide too easily over his smooth surfaces, to forget them not long after looking at them, but in their latent yearning there is a spiritual, metaphysical force at work. “If you were to meditate morning to evening,” he once said, “you would never comprehend or even fathom the unknowable hereafter.”

Friedrich’s lucidity is the foundation of his art. Yet another way to think of him is as a forefather of the light and space movement of the 1960s and ’70s. The immaterial places of James Turrell come to mind, as do Larry Bell’s glass boxes, Robert Irwin’s scrim-interiors, and Agnes Martin’s geometric haziness. Friedrich is about cosmological grandeur, and in his best work we commune with the bigness of it all. What sets Friedrich apart from everyone else is that solitary human being and his dual nature: both a tiny speck in the universe and the center of it all.

“Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature” is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through May 11.