Come for the Art, Stay for the Art

Punching Nazis is just a bonus in Indiana Jones and the Great Circle.

Indiana Jones and the Great Circle is played from a first-person perspective and involves guns, so one might reasonably assume it is a first-person shooter. In actuality, you do remarkably little shooting. Bethesda’s new tomb-raiding epic stays true to the spirit of the movies, putting far more emphasis on moving through small, dimly lit passages, torch in hand, and emerging into magnificent stone chambers illuminated by a single shaft of cascading light. Inevitably, an ancient monument looms in front of you: mysterious; beautiful; tantalizing. The game is clearly after its title character’s own heart. Yes, you get plenty of opportunities to dispatch fascists along the way using assorted bludgeoning objects, but what distinguishes The Great Circle is how it unfolds as a globe-trotting love letter to art history.

Set between the events of Raiders of the Lost Ark and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, the game — an official part of Indiana Jones canon — chronicles the hunt of not just one MacGuffin but an entire set of sacred sites that makes up the titular Great Circle. As Dr. Jones, you sneak, climb, and bound through expansive and often exotic locales like Vatican City (crawling with Italian Blackshirts), Sukhothai (home of many overgrown temples), and the pyramids of Giza (teeming with Indy’s new phobia, scorpions). The writing is stellar — witty journalist Gina Lombardi is the most compelling new character in years — which helps to make this Indy’s best outing since 1989’s The Last Crusade. Naturally, it being a faithful Indy game, you encounter lots of classic art along the way.

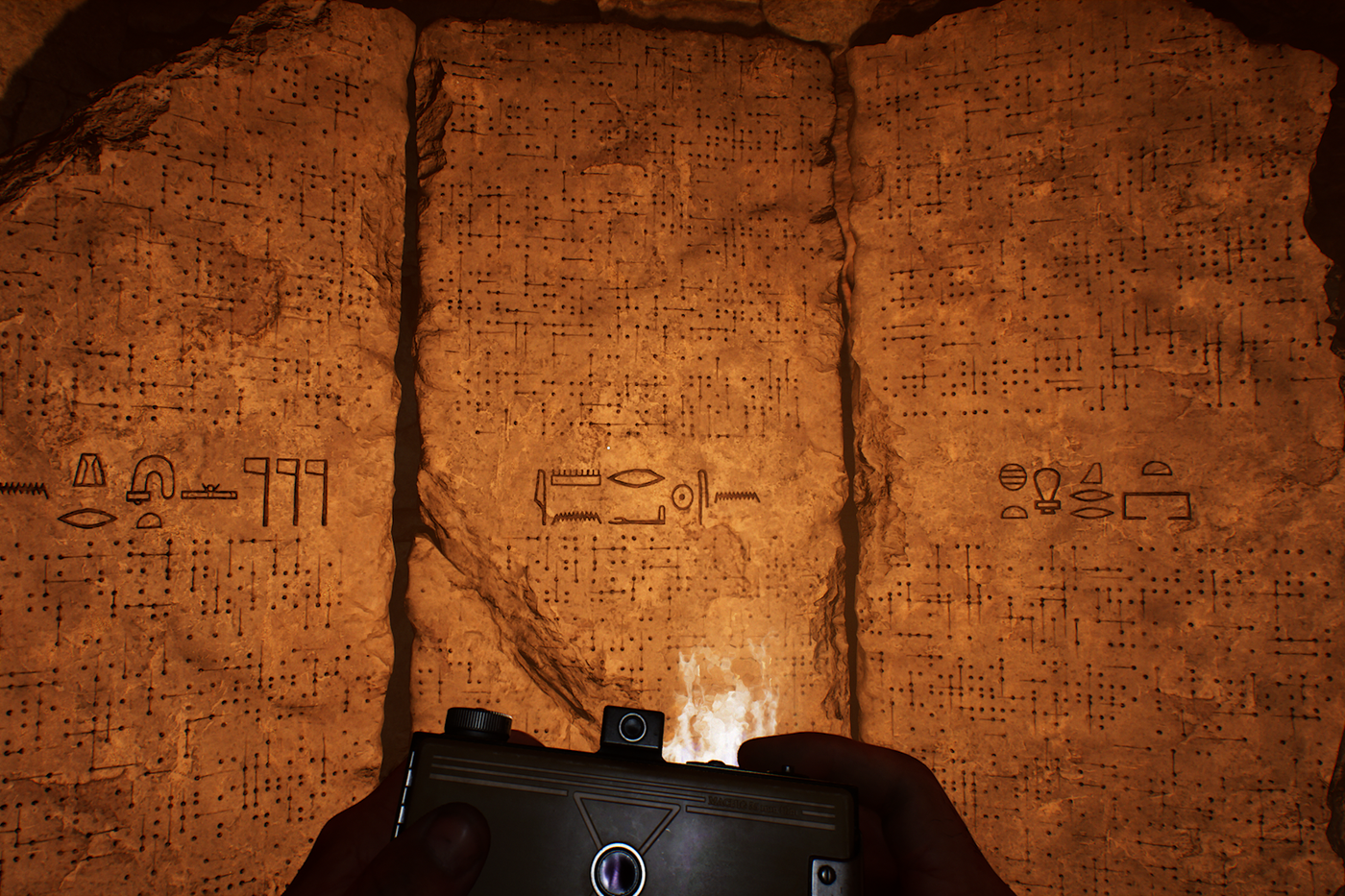

It’s this element, the way the game handles these artifacts and masterpieces, that makes it soar. That’s best demonstrated by a novel gameplay mechanic in the form of a camera that Indy acquires from a dissident postman called Ernesto. When standing in the presence of a treasure, perhaps a neolithic fertility figure or Egyptian tablet, an icon pops up in the top-left-hand corner of the screen encouraging you to take a picture. Doing so causes Jones to deliver a few scholarly lines on the given relic, incentivizing you to examine it more closely. (This Indy is voiced by gaming star Troy Baker, whom Harrison Ford likes in the role.) No longer are you just playing as Indy the rogue, whip-cracking professor; his primary vocation is that of appreciator and documentarian of these artworks. These moments are an opportunity for Swedish studio MachineGames to flex its technical chops, and, more importantly, a chance for the player to experience something of the appreciation Indy holds for these hallowed artworks of the past.

Indy’s reverence for art was hardly shared by the Nazis, who in the game are most notably represented by a loathsome archaeologist nemesis called Emmerich Voss. Art for the Nazis was a means to an end rather than a worthy pursuit of self-expression, with the objective being assertion of power and a rigid set of ethnocultural norms. The Great Circle sees the fascists tearing up earth with heavy machinery and explosives in an attempt to track down the remnants of bygone civilizations. While Indy revels in each discovery, from prehistoric caves to Art Deco images in magazines, art for Voss is merely an instrument by which the Nazis will enhance their own dominion.

The discovery of artworks functions like a visual and gameplay carrot — it’s an incentive in and of itself just to look at these beautifully rendered masterpieces. This interactive motif recurs throughout, yet it is expressed no more exceptionally than in Vatican City. Having dirtied himself in the catacombs beneath the papacy’s home, our scrappy archaeologist emerges into none other than a resplendent re-creation of the Sistine Chapel. Every famed fresco by Michelangelo, Botticelli, et al., glitters with vivid blues, rich crimsons, powdery pinks, and shimmering, reflective gold. Video games are often compared to medieval cathedrals, supreme works of art that are constructed polygon-by-polygon and texture-by-texture by artists, 3-D modelers, designers, and programmers. That characterization has rarely felt more apt than when standing in the game’s Sistine Chapel, marveling at the meticulous craftsmanship that produced both the space and the art it contains. It’s a wonder to behold.

Related