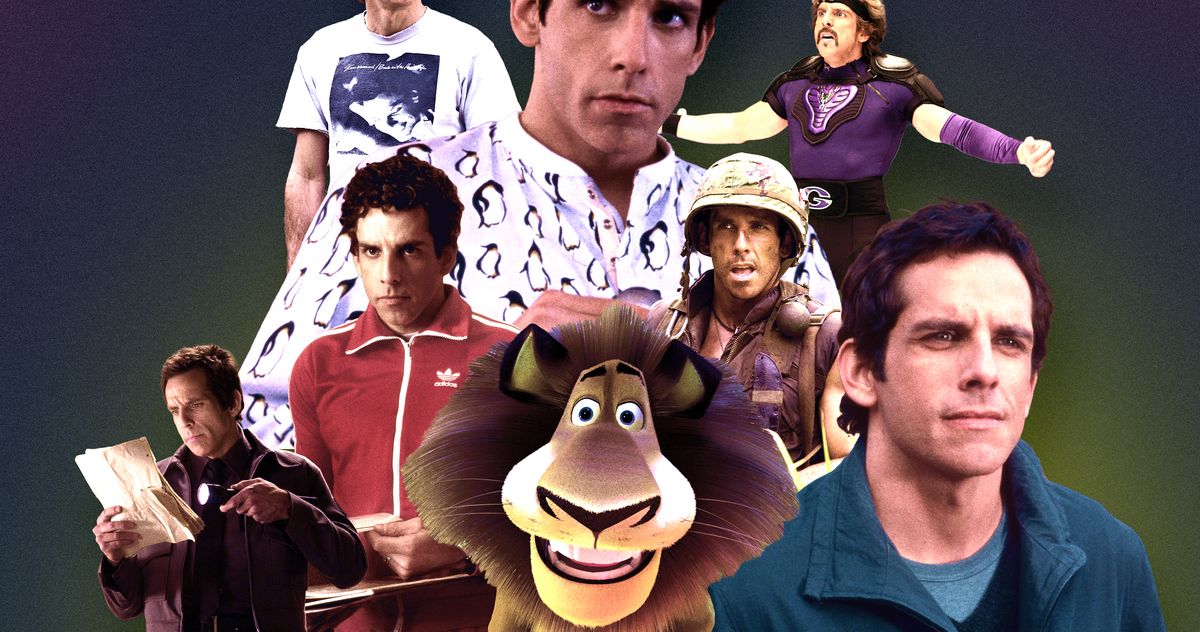

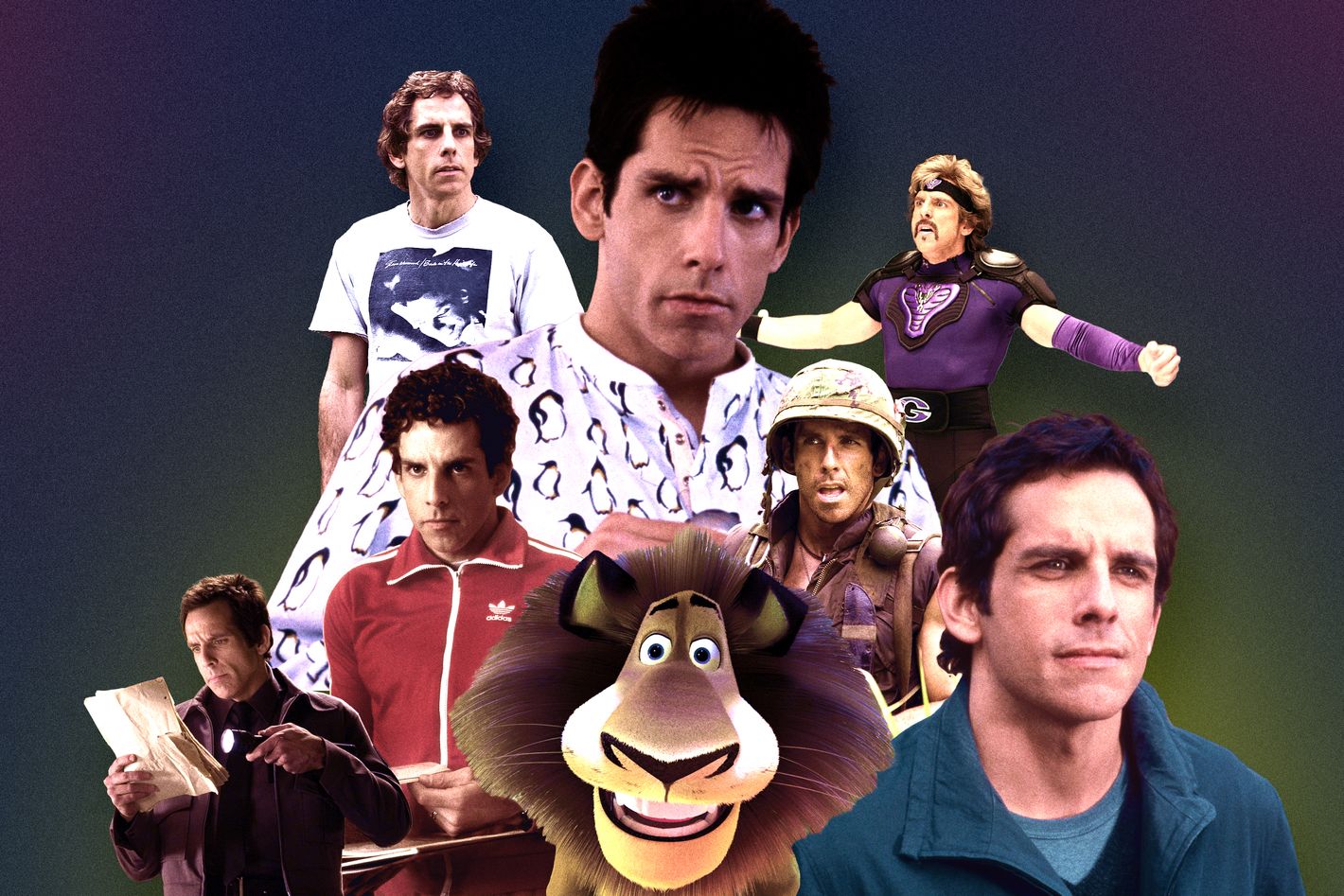

Every Ben Stiller Movie Performance, Ranked

Audiences have come to know and love many Stiller personas: jester, auteur, control freak, buff daddy.

This article originally ran in September and has been updated with Stiller’s latest film, Nutcrackers, now streaming on Hulu.

Over the course of 35 years, audiences around the world have come to love and despise many different Ben Stillers. Anyone who has seen a billboard since 1987 is sure to recognize Stupid Stiller, for example, the well-meaning lunkhead with a nasty clumsy streak but a winning warmth (“What is this? A center for ants?”). There is also Bully Stiller, the neck-bulging megalomaniacal douchebag at the end of his rope; Panicked Stiller, the anxious worrywart with a stick perpetually up his ass; and, of course, Broken Stiller, the friendless, beige sad sack marching invisibly through life. Each new iteration builds upon the last, creating a catalogue of distinct, but familiar, archetypes: Gen X’s answer to Woody Allen; a swole control freak with daddy issues; the auteur-obsessed cinephile with perfect hair. They are all, in their ways, touchstones of modern American comedy.

Then there is the “real” Ben Stiller, the actor-producer-writer-director-executive whose work on the silver screen has earned more than $3.3 billion in box-office receipts and positioned him among the Olympian elite of Hollywood megastars. The son of two revered comedians and both a husband and brother to fellow actors, the man is show business incarnate, an entertainer born into the limelight.

While his private life sometimes spills messily out into the tabloids, Stiller rarely ventures into the public eye except to fundraise for the Stiller Project, a nonprofit organization that “seeks to promote the well-being of children worldwide through initiatives that support education.” The few profiles to try and explore his inner self describe a Faustian figure, someone so singularly committed to being the audience’s fool that he has at times thwarted his own inclination toward “serious” roles. He is said to be desirous of the adoration and opportunities heaped on other actors of his generation and anxious to shed the jester hat he has worn in our collective consciousness for so long.

Stiller first gained notice on Broadway in John Guare’s The House of Blue Leaves in 1986, briefly joined Saturday Night Live in 1989, then emerged as a television star with his own acclaimed series in 1992. Two years later, he successfully pivoted to filmmaking with Reality Bites, then spent the rest of the ’90s using his burgeoning stardom to boost up-and-coming writer-directors: David O. Russell, Eric Schaeffer, Jake Kasdan, Donal Lardner Ward, Steve Brill, Neil LaBute.

After his role in 2000’s Meet the Parents cemented him as a major box-office draw, a corps of fellow hit-makers including Owen Wilson, Vince Vaughn, Will Ferrell, and Jack Black took shape, appearing in one another’s projects and dominating the cinematic landscape with irreverent, boyish humor. In this period, the persona that people know most intimately was formed: the tightwad Stiller whose dull little suburban life gets upended by an untameable wild card like Jennifer Aniston, Malin Akerman, or Jessica Alba, a figure whose overevolved sense of dread powers a well of self-hatred, entitlement, fury, and lust and who, despite irritable bowels and undiagnosed OCD, always manages to woo characters played by the likes of Cameron Diaz, Amy Adams, and Christine Taylor. In this mode, he is both jester and lover, loser and hero — the Hebrew Everyman bursting from the chrysalis of insecurity into something like adulthood.

Since 2010, however, Stiller’s star persona has taken a darker, more creatively diverse path, one that appears from the outside to align more with the real person’s true aspirations. Beginning with Noah Baumbach’s Greenberg and culminating most ostentatiously in the Emmy Award–winning Apple TV+ series Severance, which he executive produces and directs, he has in this time become Indie Spirit Award Nominee Stiller, Salt-and-Pepper Stiller, and Prestige Drama Director Stiller. Simultaneously, his face has virtually disappeared from movie screens, with the last film in which he starred released back in 2017.

Now, the 58-year-old multi-hyphenate is primed to redefine himself yet again: After serving as the opening-night film of the Toronto International Film Festival — an event often considered the kickoff to awards season — Stiller’s first starring feature in nearly a decade, David Gordon Green’s Nutcrackers, is now available to stream on Hulu (and internationally on Disney+).

And just as he begins campaigning for that overdue Best Actor Golden Globe, season two of Severance is scheduled to launch in early 2025 after a painful three-year gap. With his reemergence impending, the time feels ripe for looking back at the highest highs and lowest lows of his singular career in moving pictures.

Some caveats: As a matter of fairness, this ranking only accounts for the films in which Stiller gives fully fledged star performances. Projects in which he has minor supporting roles (think Stella, Empire of the Sun, and, more recently, Locked Down) are therefore not mentioned, nor are those in which he appears in a cameo (School for Scoundrels, Anchorman, Bros, etc.). It also excludes his extensive catalogue of television appearances, as well as the films he has produced or directed but does not appear in in any significant way.

While each of those projects deserves their own analysis too, it is by and large his cinematic performances that have shaped the world’s insatiable appetite for Movie-Star Stiller, and therefore it is only within that realm that this ranking operates. Which of his many films has stood the test of time? Which is better left forgotten? And which desperately needs to be considered anew? (*CoughEnvyCough*). Read on, dear ones, and steel yourselves for validation and disappointment both, as we are certain to disagree on at least some things. Just remember: The truest Stiller will always be the one you picture when you close your eyes.

Little Fockers (2010)

Possibly Stiller’s most cynical cash grab (his payday was allegedly $20 million), Little Fockers offers barely more than reheated gags from the previous two Meet the Parents films, though this rendition is by far the most disturbing. Male nurse Gaylord — whose toxically masculine insecurities about his overbearing father-in-law, Jack (Robert De Niro), regularly lead him to bullshit his loving, loyal wife (Teri Polo) — is now a Chicago hotshot who sacrifices his integrity by hawking off-brand Viagra to charm a Big Pharma rep (Jessica Alba). In the closest thing to funny in the whole movie, Stiller stabs two-time Academy Award winner De Niro in the dick while his toddler son watches. Later, Alba’s character tosses some of her trashy pills back with wine and winds up assaulting Gaylord in his family home. Even while pulling these shock gags, Stiller and the rest of the cast, unfortunately including icons like Dustin Hoffman, Blythe Danner, and Barbra Streisand, spend 98 minutes on “pay-me-now” autopilot. No wonder Randy Newman couldn’t be bothered to do the score.

The Marc Pease Experience (2009)

Try as he might to bury it, Stiller’s part in this broken second feature from director Todd Louiso remains a visible stain on his track record. It’s not exactly Stiller’s fault, either. His Jon Gribble, the fascistic high-school drama teacher with a delusional a capella protegee (Jason Schwartzman at his most yippy), is the film’s only serviceable creation. In fact, it may be his most successfully repulsive role ever, given the sexual relationship between Gribble and one of his teenage students (for which, I might add dumbfoundedly, he remains karmically unpunished in one of many inexplicable loose ends). Rather, the great failure of this ceremoniously dumped Paramount Vantage picture is its coherence, or lack thereof. Judging by their performances, Stiller, Schwartzman, and Anna Kendrick (as the choir girl caught between a predatory 23-year-old and a predatory 43-year-old) appear to be in completely separate movies, none of which seems particularly worth watching.

Duplex (2003)

How and why Duplex went so wrong is one of Hollywood’s great mysteries. Directed by Danny DeVito with Drew Barrymore and Stiller as newly married Brooklynites and a script by Simpsons writer Larry Doyle, it should have been a sure thing. Yet everything about this pallid stunt comedy, from the increasingly gross setpieces (at one point, Barrymore’s Nancy pukes directly into her husband’s mouth) to the wasting of normally great character actors in minor roles (Harvey Fierstein! Maya Rudolph! Wallace Shawn!), screams “misfire.” As Alex Rose, the conflict-averse new owner of a stately duplex with a Machiavellian old tenant (Eileen Essell), Stiller plays one note for the entire film: annoyance. As expert as he is with that emotion, their battle grows tiresome quickly; by the time everything is said and done, we cheer when naughty Mrs. Connelly finally squashes both her obnoxious housemates — and the possibility of a sequel.

Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009)/Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014)

Stiller embodies the “one for me, one for them” school of Hollywood careers, in which one lucrative studio flick pays for a more personal passion project. That philosophy at least gives us a modicum of insight into how these thankless, entirely redundant sequels got made. Whereas the first NATM got away with being straight-up dumb thanks to its just-don’t-think-too-much concept, Battle of the Smithsonian and Secret of the Tomb have considerably less novelty or innocence and therefore no clear reason to exist (and before you mention money, keep in mind that it isn’t illegal or even discouraged to make huge, profitable studio comedies that are also funny, interesting, and/or anti-racist). Larry Daley, the security guard Stiller plays across all three movies, was always supposed to be the straight man in a world of reanimated taxidermies, but it’s still a letdown to see him completely coast through the 100 stale callbacks that man-of-the-moment director Shawn Levy cobbles together into this weak one-two punch. Every joke is a replay from the original, from Larry’s psychotic fellow night guards (Mickey Rooney and Dick Van Dyke in No. 1, Jonah Hill and Rebel Wilson in 2 and 3) to the dinosaur bones that act like little puppies to the interminable forced-perspective gags featuring Steve Coogan and Owen Wilson as homosocial model miniatures. Worse yet, Stiller looks genuinely miserable throughout both sequels, particularly in Secret of the Tomb, his famously lined cheeks pulled down unwittingly into a sour frown in nearly every shot. One wonders what kind of passion project was possibly worth facing off against Hank Azaria as a lisping Egyptian king complete with ancient headgear. Who cajoled him into bringing not one, but two slap-happy capuchins into the mix? Keep playing the same old hits, and you wind up starring in “Now That’s What I Call Cinema.”

Mystery Men (1999)

On a hillside overlooking beautiful Champion City, an animatronic skunk has sex with Paul Reubens. Take it or leave it, that’s the comedic level at which Kinka Usher’s tongue-in-cheek, anti-superhero film operates. There are parts of Usher’s bubble-gum dystopia that help Mystery Men still feel novel 22 years after release, like the villainous goons obsessed with disco, Tom Waits’s junkyard of nonlethal inventions, and Michael Bay playing a decent human being. Then there are moments like the skunk thing or Hank Azaria’s (yet again poorly justified) East Asian accent, which one imagines scored quite badly in most test screenings yet somehow made it into the finished film anyway. Stiller’s Roy, the leader of the titular supergroup, is rarely more than a wet blanket, literally powerless and mopey right until the climactic battle. Unlike in Stiller’s best roles, Roy’s relationship with a waitress played by Claire Forlani seems entirely forced. Watching it today, Mystery Men feels like the one that got away for Stiller, who was at his physical peak and should have been able to Paul Rudd his way into a fun-loving comic-book franchise with more ease. Perhaps predictably, Usher never directed another feature. But on the bright side, at least he got Dane Cook and Ricky Jay to star in a movie together.

Zoolander 2 (2016)

No character is more closely associated with our man than the dim-witted but really, really, ridiculously good-looking male model Derek Zoolander. This is for good reason: the first Zoolander, beloved by millennials and Terrence Malick alike, is a landmark in his career (and, spoiler alert, ranked much higher). But with such adoration comes added responsibility, a fact Stiller and his team should have considered more deeply before unleashing this undercooked, overplotted sequel on the world. Where the first film’s satire of over-the-top couture and Met Gala starfuckery was so on point, the second feels like a double dip with Stiller as the proverbially stale cracker. His co-stars, like Will Ferrell’s savage Mugatu, Owen Wilson’s stoner hottie Hansel, and Nathan Lee Graham’s servile Todd — all so precise and well-defined in the original’s ravelike milieu — are doomed to retrace their old steps here. Even the litany of topical cameos, a touchstone of the franchise, comes across as faintly desperate. Undeniably beautiful as the sight of Justin Bieber getting mowed down in cold blood is, the film just doesn’t work.

The Watch (2012)

I’m just going to say it: Ben Stiller is not built for sci-fi. I don’t mean physically (the dude is scientifically proven to be as jacked as Tom Cruise or any Hemsworth) so much as emotionally: Even at his most committed, he lacks the particular kind of brutal, masculine intensity needed to make screaming at a CGI-ed tennis ball feel real. It certainly doesn’t help to have aliens as ridiculous looking as those in Akiva Schaffer’s product-placement-choked follow-up to Hot Rod, nor to have the thinnest character arc in an already thin script. With all the laugh lines going to Jonah Hill, Richard Ayoade, and Will Forte’s mustache, Stiller’s normally bankable stolidness becomes this disappointing film’s ball and chain. At one point, Vince Vaughn’s neighborhood-watch lieutenant even calls Stiller’s sterile Costco manager, Evan, a “control freak” — which is to say he’s no fun at all.

Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa (2008)

Despite a disturbing opening sequence filled with weirdly bubbly mammalian asses swaying in unison, this slight sequel still contains a few unexpected pleasures: a mid–30 Rock Alec Baldwin as a dastardly pompadoured lion; Sacha Baron Cohen’s mischievous King Julien’s constant abuse of Andy Richter’s Mort; this brain-melting crap. Stiller’s Alex the Lion, ostensibly the leader of the pack, takes a welcome back seat here, leaving the focus on the romance between David Schwimmer’s nervous giraffe, Melman, and Jada Pinkett Smith’s Gloria the Hippopotamus (show us their monstrous kids, Jeffrey Katzenberg!). As a result, M:E2A earns its stripes through an abundance of heart, even with some of the first film’s humor M.I.A. (those malevolent penguins, for example, are foolishly sidelined). That said, if I have to hear will.i.am’s five-minute cover of “I Like to Move It” ever again, I too will volunteer to sacrifice myself to the nearest volcano.

Meet the Fockers (2004)

Any fellow chosen people out there really feel it when Barbra Streisand yelled, “This is the fruit of your loins!”? For me, that’s the honest-to-goodness high point of this spottily funny redo, unless you count every time Jack Byrnes’s grandson says “asshole.” That is pretty good shit. Still, with Stiller and De Niro both in fine frenzied form and game appearances from Streisand and Dustin Hoffman as Greg’s loose-limbed parents, Meet the Fockers really should have kicked this blockbuster franchise up a notch. Instead, it cuts some unacceptable corners with regards to its characters of color and handily fails the Bechdel Test to boot. There is also more than a hint in this go-around that Greg’s constant lying to Pam is something more pathological than protective, yet Stiller and the ever-patient Teri Polo play this compulsion entirely for laughs. Sure, I laughed with them when I first saw it, but trust me: A post–Me Too rewatch hits different.

Night at the Museum (2006)

Watching Ben Stiller get slapped around by a little monkey tickles a primitive spot in the human brain. It’s debased, silly, violent caveman comedy (literally), and it works like a charm. Night at the Museum is purely a vector for gags like this, some of which will remain lodged in the cultural memory forever: an Easter Island head asking for chewing gum, for instance, or Larry being toppled, Gulliver-style, into a diorama. Yet none of screenwriters Robert Ben Garant and Thomas Lennon’s jokes are strong enough to mask the emotional emptiness on display in this, the kind of effects-heavy and content-lite movie parents worry might give their kids ADHD. Riddled with unnecessary scatology (weirdly, we’ve all seemingly forgotten that same capuchin actually pissing into Stiller’s mouth and eyes) and nasty pseudo-historical stereotypes, it’s a journey to nowhere for every character except Teddy Roosevelt, whom Robin Williams endows with just enough of his trademark sweetness. Even frequent Stiller collaborators like Owen Wilson and Steve Coogan fall short, rendered unfunny by a combination of weak material and poorly aged VFX. Where’s Noah Baumbach when you need him?

If Lucy Fell (1996)

Decked out like the unholy offspring of Adam Duritz and Jean-Michel Basquiat, Stiller somehow steals every scene in this otherwise insipid quirkfest. In true mid-’90s fashion, he plays a celebrity action painter called — if you can believe this — Bwick Elias (Bwick?!) whose intense, self-obsessed pretension is so great that he can barely sputter out his feelings for a pre–Sex and the City Sarah Jessica Parker. Big as the performance is, Stiller isn’t alone: Writer-director-star Eric Schaeffer also pillages shamelessly from the Sundance playbook of whimsy, giving himself the lion’s share of irony-laden pickup lines and depressive witticisms about the pointlessness of romance. Naturally, it’s Schaeffer’s staunchly independent painter who gets the girl, despite the fact that anyone with two eyes and a brain would be drawn to his far more charismatic (if inexplicably dreadlocked) rival.

The Heartbreak Kid (2007)

Stiller’s second film with the Farrelly Brothers is, for the most part, a miserable grotesquerie. Remade from the 1972 original directed by Elaine May (a masterpiece of dark comedy, ironically enough), it centers on Eddie (Stiller), a lovelorn San Franciscan pushed into a shotgun marriage with Lila (Malin Akerman) by the insecure combination of his own internalized sense of sexual entitlement and his team of goading, misogynistic yes-men. Eddie soon discovers that Lila is a “nightmare” — which is to say she eats, sleeps, fucks, and lives differently than him, therefore making her unworthy of his heteronormative social status and the reason he pursues an emotional affair with a more salt-of-the-earth woman (Michelle Monaghan, in the film’s sole redeeming role) on his Mexico honeymoon. Only in its final scene (in which Eddie, once he’s scorned by Monaghan’s Miranda, is revealed to have instantly taken a third wife, played by Eva Longoria) — do the Farrellys reveal their true message: that white men like Eddie are duplicitous scum who use their social capital to reinforce patriarchal power over women and manipulate them into domestic servility. Well, fair enough.

Keeping the Faith (2000)

A priest and a rabbi fall in love with a blonde … it certainly sounds like the setup for some broad rom-com, but in execution, Edward Norton’s directorial debut is far more contemplative than its premise — to its detriment. Working from a script by Oscar nominee Stuart Blumberg, Norton focuses on how two adorable best friends use pained humor to survive personal crises of faith, rather than on those crises themselves, as so many films about clergy tend to do. Nor are their jokes, for the most part, cheap. Both Stiller (as the rabbi) and Norton (as the priest) invest their deliveries with a certain shared cynicism, a lived familiarity, and, particularly in Stiller’s case, a garnishing of his standard sexual desperation. So why are neither funny? It comes as no shock that the two never worked together again. There is also, it must be said, something thankless in Jenna Elfman’s role as the apple of both men’s eyes. Since it is never in doubt whose arms she’ll fall into (one of the two isn’t allowed to have sex, so you do the math), the love triangle powering Blumberg’s drama lacks all tension. What’s left are three cautious, easygoing performances in a film with no drive — competent, for sure, but ultimately a bit ponderous.

Black & White (1999)

Come, let us journey to the year 1999, when white women wore cornrows with impunity, gangsta rap was still fighting to be taken seriously in the music industry, and James Toback could still get a new feature greenlit. Black & White is a solid time capsule of this confusing era and more, a multi-narrative thriller in the hyperlink-cinema tradition with a massive star-filled cast. You’ve got Robert Downey Jr. as a barely closeted documentarian, for example, as well as Brooke Shields as his Dolezal-like beard, Elijah Wood as a teenager desperately trying to fit in with Black people, and Ben Stiller as a philosophy-spouting cop using racist methods to clear his filthy record. Toback’s script is as ambitious as ever, weaving together threads around miscegenation, queerness, class-based violence, cultural gatekeeping, and nonfiction cinema with far more intensity and idiosyncrasy than, say, Crash or Green Book. Most of the cast rises to meet the quality of his inimitable patter, particularly in the cases of Stiller, Claudia Schiffer, and Joe Pantoliano, upon whose backs the core mystery hinges. It might still work as entertainment 21 years later if not for the fact that friends of Toback’s like Mike Tyson and Brett Ratner also make distractingly prominent appearances.

Zero Effect (1998)

Screenwriting scion Jake Kasdan’s first film is difficult to find now, a largely forgotten blip in both his career and that of his two leads, Bill Pullman and Ben Stiller. That’s a shame, because they make quite a fine Holmes and Watson, respectively, to Kasdan’s Conan Doyle. Zero Effect appears at first glance to be a classic Sherlock rip-off, complete with a hyperintuitive, drug-addled detective, his anal-retentive assistant, and a dangerously appealing femme fatale. But like his characters, Kasdan is too clever for his own good, turning what begins as an otherwise derivative murder mystery into a lean parable on class and the American health-care system in its third act. Within that context, Stiller is quite an effective second fiddle, all the more so when you consider that this gripping, cynical drama came out the same year as There’s Something About Mary. Watch them together and the range between his performances becomes something to behold.

Tower Heist (2011)

It is unfortunate that Stiller’s rock-solid work in this class-conscious crime caper got overshadowed in release by its director. The film is anchored by Stiller’s Josh Kovaks, who manages the struggling employees of a Trump-style tower and acts as a friend to all of them when the pissant billionaire owner (Alan Alda) goes full Madoff (his working victims are played by a litany of world-class character actors: Michael Peña, Gabourey Sidibe, Stephen McKinley-Henderson, Nina Arianda). Unusually for Stiller, however, Kovaks is also almost entirely ticless: neither neurotic nor anxious, overconfident or abrasive, he’s just an ethical, normal person. Other big name co-stars, including Eddie Murphy as Kovaks’s criminal compadre and Matthew Broderick (in his finest performance since Election), get the laughs, but it’s Stiller’s, er, towering performance as a man whose most distinctive quality is being a big sweetie that steals the film.

Starsky & Hutch (2004)

Like every Todd Phillips movie, this light-hearted reboot of the classic 1970s buddy-cop show is about twice as good as it needs to be. That is almost entirely thanks to the time-tested chemistry between Stiller and Owen Wilson, each perfectly typecast as the resident sexy neurotic and his sexy airheaded partner. Look, it’s no Joker, but Phillips gets the job of making you laugh done with the same douchey, casually chauvinistic confidence he brought to fratsterpieces like Old School and The Hangover. Come for the anxious-but-effective cop and his smarter-than-he-seems partner going toe-to-toe with a mustachioed Vince Vaughn, stay for the Dan Band serenading a 13-year-old’s bat mitzvah with a nasty cover of Roberta Flack’s “Feel Like Makin’ Love.”

Reality Bites (1994)

Helen Childress, the writer of Reality Bites, has said that its title refers to small chunks of real life rather than the experience of living through the dumpster fire of George H.W. Bush-era America. If that’s true, then Ben Stiller, who chose the feature as his directorial debut, definitely did not understand the assignment, given that the finished film is about four cynical burnouts struggling to pay rent while making lo-fi Soderberghian documentaries. Regardless, Gen-X nostalgists and their offspring have long since anointed it an era-defining cinematic Bible of the early 1990s in the legacy of Slacker and Singles, and it remains among Stiller’s most treasured movies. Reality Bites also demonstrated his aptitude at directing himself in starring roles: His performance as the principle-free, tie-wearing exec fighting with his polar opposite, the rock musician and poetry-spouting asshole Troy (Ethan Hawke), over Winona Ryder’s Lelaina Pierce expertly straddles the line between appealing and appalling. In fact, all but one of the projects Stiller both directed and starred in show up later on this list.

Nutcrackers (2024)

Seven years stand between Stiller’s career-high one-two punch (Brad’s Status and The Meyerowitz Stories) and Nutcrackers, his first leading role for director David Gordon Green. Yet evidence that he kept in fighting shape in the interim — directing and producing Escape at Dannemora and Severance, two of his very finest achievements, certainly helped — is palpable throughout nine-tenths of the film. Against a cast stacked with comedy heroes like Linda Cardellini, Tim Heidecker, and Edi Patterson, all pitch perfect, Stiller allows himself to go remarkably small as Mike Maxwell, an all-business Porsche owner tasked with quickly finding a foster family for his four naughty nephews after the sudden death of their mother (his estranged sister). Fusing the signature moseying energy of his renowned rural indies with the gentle mischief of Big Daddy, Green locates spots of sentimental magic in his star’s frown, particularly in a climactic dance sequence that stands among the gentlest endings in the actor’s long career (I blubbered, if you must know). Where the production falters is in its clunky mix of tones, undercutting Mike’s hard-won heroism with two or three desperate-to-please moments of clownishness that are sure to remind those watching over the holidays of harder-core comedy classics like National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation and Ernest Saves Christmas. The lesson? If you want your film to fly high, let Stiller stay low.

Along Came Polly (2004)

Yes, this film only truly “works” when our lord and GOAT Philip Seymour Hoffman is onscreen. But there would be no grease-drinking, Judas-playing Sandy without his anal-retentive best friend, Reuben Feffer. As the pathologically risk-averse soyboy trying to woo Jennifer Aniston’s Polly Prince, Stiller amps Feffer’s mania up to 11: Any time he sweats, pukes, squirms, dances, or has diarrhea because of Polly, he does so with anguished gusto. Unfortunately, his is a multi-octave performance stuck in a primarily one-note movie that also features what must be Hank Azaria’s worst accent ever (well, maybe second worst). He and Aniston (fun but underused here as a brainless dolt) are due for a rematch. Let it rain!

Meet the Parents (2000)

In some ways, this is Stiller’s ur-blockbuster, a marvel of Rube Goldbergian steam-building with hundreds of potty-mouthed jokes undergirding it all. So many of the set pieces are inspired, so many quotes are iconic (“I have nipples, Greg …”), and De Niro gives his funniest performance of all time, so much so that his aptitude as a comedian has never been questioned since. The movie’s not without problems, of course: There was never anything inherently funny about the name “Gaylord,” for instance, or male nurses, and that is especially true in 2024. Still, watch how quietly Stiller transitions Greg Focker from put-upon beta to the spastic, sputtering alpha he’s become world-famous for playing. All things considered, we’re talking about a bona fide classic here.

While We’re Young (2014)

It’s fortunate for everyone that the second of Stiller’s starring roles in a Noah Baumbach film also coincided with the second collaboration between the acclaimed writer-director and Adam Driver because they level each other beautifully, with Driver bringing out the rageful undercurrent of Stiller’s tried-and-true depressed-dad persona and Stiller, in kind, enabling the inherent goofiness in the younger man’s intimidating physicality. Their scenes together as self-obsessed mentor and devious mentee are snakey and silly and tragic all in one; actually, Stiller finds choice moments with all of his scene partners, particularly Maria Dizzia and Beastie Boys’ Adam Horovitz as his upsettingly comfortable New York buddies as well as Charles Grodin (Hollywood’s proto-Stiller) as the Pennebaker-esque documentarian that Stiller’s Josh Srebnick wishes he was. Less suffocating than Greenberg yet more optimistic than The Meyerowitz Stories, WWY remains the frothiest and arguably most outright fun of Baumbach and Stiller’s work together (unless you consider the below …).

Madagascar 3: Europe’s Most Wanted (2012)

Martin Short as a crazed Italian circus sea lion! Frances McDormand as an Edith Piaf–singing animal murderess! The Penguins “Baba Booeying” one another! Who could have predicted that the third (and potentially final) chapter of this massive children’s franchise would wind up being the most balls-to-the-wall animated film of the 2010s? The evidence suggests that Stiller and series directors Eric Darnell and Tom McGrath (with assists from Shrek 2 director Conrad Vernon and Stiller whisperer Noah Baumbach) must have felt boxed in by the required formulae of the previous movies or else vengeful against their overlords at Dreamworks. Their revenge? This wild acid trip — for kids! Alex mating with an Italian trapeze jaguar is only the tip of the weird-joke iceberg.

Envy (2004)

Stupidly mismarketed and resultantly misunderstood in its time, Barry Levinson’s idiosyncratic and still crackingly funny Envy features the first and only true Stiller–Jack Black two-hander. Frankly, that sucks, because as former best friends Tim Dingman and Nick Vanderpark, they are inarguably terrific together. Dingman is all hollowed-out resentment at Vanderpark’s oblivious, insufferable kindness; they are oil and water in the best way, both performers totally in equal-but-opposite flows as Vanderpark’s Va-Poo-Rize fortune sends Dingman into a dangerous, bumbling rage. Levinson’s twisty, almost noir tone (Dutch angles and murderous drifters abound) makes the litany of sight gags on display twice as funny. Sure, we expect the bum (Christopher Walken at his Walkeniest) who helps Dingman plan his best friend’s murder to double cross him, but not to get an arrow shot into his shoulder. Vanderpark is an unusually rich part for Black, too, one of his more wide-eyed, mellow performances in the Bernie vein. But it’s Stiller’s self-righteous jealousy — never more potent a tool in his kit — that tethers their relationship to something genuinely painful.

Heavyweights (1995)

What is it about this Steven Brill comedy that so resonates with children of the 1990s? It’s not particularly great as, like, cinema. Nor is its message especially body-positive or life-affirming in any way (if you remember it as a loving ode to fat kids, try watching it again). But Stiller’s Tony Perkis — one of a few beefcake villains in his oeuvre — pushes every scene to an extreme with manic, malevolent focus. Sporting Richard Lewis hair above a Tony Robbins smile, Perkis is part tyrannical camp counselor, part abusive daddy, and, to this day, one of Stiller’s most committed, outrageous character roles. The performance is so vibrant that those who found the film on a late-night Disney Channel rerun are still hard pressed to forget him licking the ground mid-pushup more than 25 years later (take it from me). Given that Stiller himself is notoriously particular about his characters’ looks, there’s also a worthwhile thesis to be written on Perkis’s psychotic behavior as a mirror for Hollywood’s expectations of its stars. Film students, get those dissertations ready …

Your Friends and Neighbors (1998)

If you ever want to watch Ben Stiller fully cuck Aaron Eckhart, here is your one and only opportunity. Together, they are two of the devilish six-part choir assembled in Neil LaBute’s symphony of domestic hostility. Reviews of the film at the time tended to single out the career-best performance of Jason Patric, primarily because, as the aggro, rape-minded workout buddy to Eckhart’s weak-spined Barry, Patric’s is the showiest and most sickening role. Don’t ignore Stiller, though: With his coiffed little goatee and professorial wire-rims, his Jerry is every bit the predatory equal of Patric’s Cary, especially when it comes to his female acting students. In a movie about trash people hurting one another because of horny, Jerry is arguably the cruelest, wrapping his manipulative, coercive behavior inside the guise of artistic malaise and sensitivity. Stiller digs deep into and implodes the archetype of the Nice Jewish Boy with such palpable pleasure that his scenes almost feel fun, at least compared to the arch misery with which LaBute so skillfully colors the rest of the movie.

Permanent Midnight (1998)

“Based on an allegedly true story of TV writer Jerry Stahl with a $5,000 a week job and a $6,000 a week habit.” This somewhat glamorous tagline from the Permanent Midnight marketing campaign does the film adaptation of Stahl’s same-named autobiography no favors, disguising as it does the brutal self-abasement brought out in Stiller’s bravura performance as Stahl. His is the kind of role critics normally call “raw” or “transformative”: a completely embodied, often stomach-turning portrait of eyes-rolled-into-the-forehead, veins-popping-from-the-neck addiction. In a more just world, Stiller would have been an immediate contender for an Academy Award, or at least one of those conciliatory Golden Globes given to comedians brave enough to break into drama. Perhaps the confusion comes from director David Veloz’s attempts to have it both ways tonally, presenting Stahl in the throes of heroin withdrawal in one scene then goofing off with Andy Dick on Maury in the next. Between some shots, we barely have enough time to stop crying before we are asked to giggle. Even so, what should have been Stiller’s The Truman Show wound up more like his The Majestic: a lost opportunity to bring overdue prestige to a star it has long eluded.

The Meyerowitz Stories (2017)

The message of Noah Baumbach’s tenth feature? Be careful what you wish for. After two-plus decades of the public’s begging for a comedy team-up, Baumbach finally managed to bring Ben Stiller and his exact doppelgänger, Adam Sandler, together in a talky, dreary drama about childhood sexual trauma and the inevitability of dying a failure. Don’t get me wrong — it’s a brilliantly funny film, evocative in its forlorn and stately misery of Bergman’s family dramas with a few pinches of Annie Baker’s soft humanism in the mix. But it’s also a shock to see America’s most lovable Jews throw hands on the Bard quad. That Stiller, Baumbach’s favorite muse under six-foot-two, is relegated to the quiet role in an ensemble of renowned stage and screen actors is no accident; no one writes to Stiller’s soft side with more moral generosity than Baumbach. As the last remaining bastion of sanity, patience, and responsibility in the self-sabotaging Meyerowitz clan, Stiller is heartbreakingly real. Rumor spread some years back that Stiller and Sandler were due back together soon in an upcoming film. On the basis of this, consider us stoked.

Madagascar (2005)

For a brief moment in 2005, there was simply no escaping “I Like to Move It.” Fans of a pre-Borat Sacha Baron Cohen, who sang the ragga earworm as the lemur King Julien, were probably pleased; parents of young children must have been miserable. Either way, thanks in no small part to its ubiquity, Madagascar made $555 million at the box office and kickstarted a massive new franchise for Dreamworks. Unencumbered by the neurosis or abject horniness of his standard live-action roles, Stiller is gently fraternal as the voice of Alex the Lion, the franchise’s core mammal and group leader. Co-stars like Baron Cohen, Chris Rock, and David Schwimmer get most of the good laugh lines, but Stiller is the beating heart of this first film, carrying Alex out of the insufferable vanity he inherited as a star at the Central Park Zoo to a place of self-acceptance in the wild like a leonine Siddhartha. It’s genuinely touching.

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (2013)

The film that Stiller the director was always meant to make. Perhaps unsurprisingly, audiences struggled with Walter Mitty. While its first trailers suggested a potential awards power player, reviews were ultimately middling, in part because it pivoted on one of the most charming men in cinema being made to appear completely charmless — and succeeded too well. Stiller is at his most fragile ever onscreen as an internalized shell of a man with a gray aura and an almost suicidal loneliness. To see him as James Thurber’s nowhere man is to weep for him, until, predictably, he beats his bully (his neckbeardy future Severance star, Adam Scott) and gets the girl (Kristen Wiig). Look deeper than the “khaki-loving sad sack self-actualizes by skateboarding on a volcano” plot, though, and a more nuanced narrative appears: that of a Hollywood comedy director finally emerging from the purgatory of broad-strokes franchise filmmaking into the most visually and tonally mature work of his career.

Dodgeball: A True Underdog Story (2004)

Six words for you: “Dodge, duck, dip, dive, and … dodge.” If that doesn’t make you giggle, then you have a heart made of stone. No one would call it subtle, but Rawson Marshall Thurber’s dumbass sports comedy has aged like gas-station wine, which is to say it’s as funny as ever and gets you rightly fucked up. Most of the laughs are of the uncontrollable variety, triggered by the sight either of Stiller’s napoleonic White Goodman spitting bile at Vince Vaughn’s hapless rival and straight man, Peter La Fleur, or of some strangely dressed Europeans getting pelted in that most amusing of body parts. There are also fart jokes, piss-drinking, illiterate hobo pirates, and Missi Pyle with a unibrow and fangs, all of which still go straight to the comedy jugular 20 years after the film’s release. It’s as close as Stiller ever got to making Jackass, and it’s long past time we got a sequel.

The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

One wonders why Wes Anderson’s ever-expanding retinue of regulars never again included Stiller after this first everlastingly delicious collaboration. He is just magnificent, all grief and wound and shatter, as Chas Tenenbaum, the least measurably accomplished of Royal and Etheline Tenenbaum’s children. It is beyond hack at this point to call an Anderson film impeccable, or to say that the worlds created in his work reflect a control of image, design, and sound so precise as to seem almost arid. Yet Chas and his squirrelly fury disrupt Anderson’s normal diorama. Against the droll sadness brought to the table by Luke Wilson, Gwyneth Paltrow, and Bill Murray’s performances, Chas lights up with a ferocious volatility that feels directly leached or learned from Gene Hackman’s Royal. Because he stands out so vividly, many of the film’s most iconic visual motifs belong to Chas: the track suits, the perm, the spotted mice. Perhaps this is why Anderson has yet to work with Stiller again: He shines too brightly in work that normally reflects its director’s authorship. Or maybe I’m just reading into it and the right reconnection simply hasn’t revealed itself. Either way, I hesitate to get too greedy. We are already so lucky just to have this jewel.

There’s Something About Mary (1998)

It’s easy to remember the splooge in Cameron Diaz’s hair or the fish hook in the mouth. What often gets forgotten when we talk about There’s Something About Mary is the rubbery physicality that Stiller brings to his role as Ted, the brace-faced loser whose eventual glow-up lands him a date with the girl of his dreams. Under the Farrelly Brothers’ direction, Stiller is at his most frantic, nasty, combustible, and debased; he is, in short, comedy incarnate. Add to that his chemistry with Diaz, a performer every bit as game as he is for the Farrellys’ signature puerility (and long overdue herself for a truly challenging role), and you get an unimpeachable classic with two electrically funny movie stars at the top of their game. You’ll never look at a zipper the same way again.

Zoolander (2001)

The last 20 years have been very kind to Stiller’s magnum opus. Gaudy, sweaty, and drenched in glitter, Zoolander was as high-concept as Hollywood comedies got in its era, a Pop Art–inflected karate thriller with a Nyquil-drunk fever-dream rhythm and the dialogue of an early Apatow stoner buddy flick. Its bombastic send-up of the fashion world was rivetingly, colorfully surreal, and it is the rare comedy that meme culture has only made better. In a way, demonic performances like Will Ferrell’s as the fashion assassin Jacobim Mugatu or Justin Theroux as a bug-eyed DJ were just a series of timeless GIFs stapled together in the edit. Even so, this is undeniably Stiller’s film. On top of the fact that he co-wrote, produced, and directed it, Derek Z. remains his (and Drake Sather’s) signature creation, the all-time stupidest of the Stupid Stillers as well as the most organically quotable. Not enough is said about Stiller’s dexterity as a director, either: After the pseudo-documentary vibes of Reality Bites and the Farrelly-tinted black farce of The Cable Guy, Zoolander, his third feature, cemented his credentials as a genre-hopping journeyman director in the vein of Sidney Lumet, Jonathan Demme, or John Frankenheimer (whose The Manchurian Candidate serves as one of the film’s key points of inspiration). It careens wildly between action and satire, soft-core porn and underwear advertisement, without ever losing its sparkling sense of inherent silliness. As a result, the movie has grown into its reputation as one of the great cinematic tentpoles of the early millennium, and, for better or worse, is probably the only movie guaranteed to appear in every Ben Stiller career retrospective once he retires. That’s something that even Zoolander 2 can never destroy.

Brad’s Status (2017)

A few years before he masterminded the global phenomenon that was The White Lotus, creator Mike White spearheaded this searching and criminally underrated indie two-hander about a father and son touring prospective colleges. Stiller, going full silver fox, displays heretofore unseen shades of melancholy as Brad Sloan, a medium-successful married man whose banal accomplishments as a nonprofit worker start to seem like failures. As his boy Troy, who wants nothing less than to reminisce about or meet Dad’s more successful college friends, Austin Abrams is every bit Stiller’s equal. Troy’s deceptive sullenness masks a profound understanding of Brad’s crisis, and their argument scenes, which White inserts almost as chapter breaks between colleges, are wrenching as the realities of Brad’s pain and Troy’s profound understanding of it collide. Those scenes alone make this exquisite drama from one of the best writer-directors in the game worth every minute.

Greenberg (2010)

Leave it to Noah Baumbach, that poet of upper-middle-class pain, to fully unearth the latent dread that powers Stiller’s star persona. Given its appearance at the end of a decade-long run of blockbuster comedies, Greenberg is most easily compared to Paul Thomas Anderson’s Punch-Drunk Love with Adam Sandler, though only inasmuch as both films allowed their stars to shuffle off the handcuffs of farce and commit to something more sincere. Greenberg, however, is hardly the arthouse film that PTA’s is, borrowing more from the then-popular mumblecore school instead, including by featuring that movement’s greatest star, Greta Gerwig, as Roger Greenberg’s hook-up buddy (Mark Duplass, another mumblecore pioneer, appears as one of Greenberg’s bandmates). As Greenberg, a carpenter on the back end of a nervous breakdown, Stiller lets his normally muscular shoulders slump forward and his eyes refuse to light up with their famous blueness. It is a sad, perfect performance made all the better by being exactly the kind of thing Tugg Speedman could only dream of starring in.

Tropic Thunder (2008)

Who left the fridge open? Tugg Speedman, the action star at the center of Damien Cockburn’s (Steve Coogan) titular Vietnam epic, is Stiller’s greatest idiot, a roided-out narcissist with a photogenic face and a penchant for making trashy Hollywood product despite his best efforts. Stiller and his co-writers Etan Cohen and Justin Theroux’s genius is to surround Speedman with even dumber dipshits: his drug-addled sellout co-star, Jeff Portnoy (Jack Black); the overcommitted Australian Method actor Kirk Lazarus (Robert Downey Jr.); and a dozen other red-blooded maniacs sweating it out in the jungle. Again serving as director and producer in addition to writing and starring, Stiller succeeds in making his cleverest and most savage satire — yet, oddly, it contains his most underrespected role. That he did not receive an Academy Award nomination while RDJ did is still stupefying. Simple Jack forever.

Flirting with Disaster (1996)

In Flirting with Disaster, we reach three apotheoses in one: that of Stiller’s peerless portrayal of the harried, sexually hysterical Jewish husband; his lifelong obsession with working with American auteurs; and David O. Russell’s early career as one such filmmaker. Their collision point results in one of the funniest screwball comedies of the modern era, a pervert’s homage to It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World brought to life by a cast of legends: Mary Tyler Moore, Alan Alda, Lily Tomlin, George Segal, Richard Jenkins, Josh Brolin, Patricia Arquette, Téa Leoni. That Stiller stands out amid this crowd as a jumpy little man looking to kick his stalled married life back into high gear by finding his biological parents is a testament both to his gifts as the world’s most frantic clown and to Russell’s generous, madcap labyrinth of a script. To watch Stiller leap maniacally at Leoni (the first time to “wrestle” her, the second to woo her) is to see the ’90s-buff answer to Charlie Chaplin come into his one-of-a-kind comedy timing for the very first time. In a lifetime of mighty physical performances, Stiller has never been more limber, more appealing, or more expressive than he is here. Hell, even Chaplin needed a cane to get his point across.

Related