How Did This Feel So Intimate?

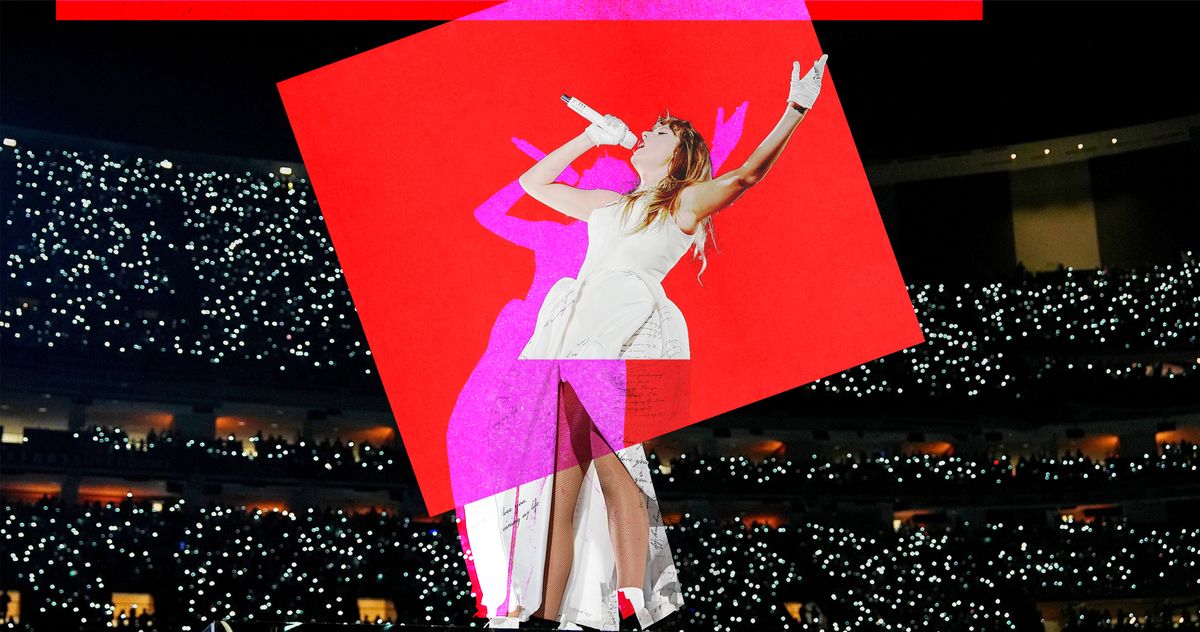

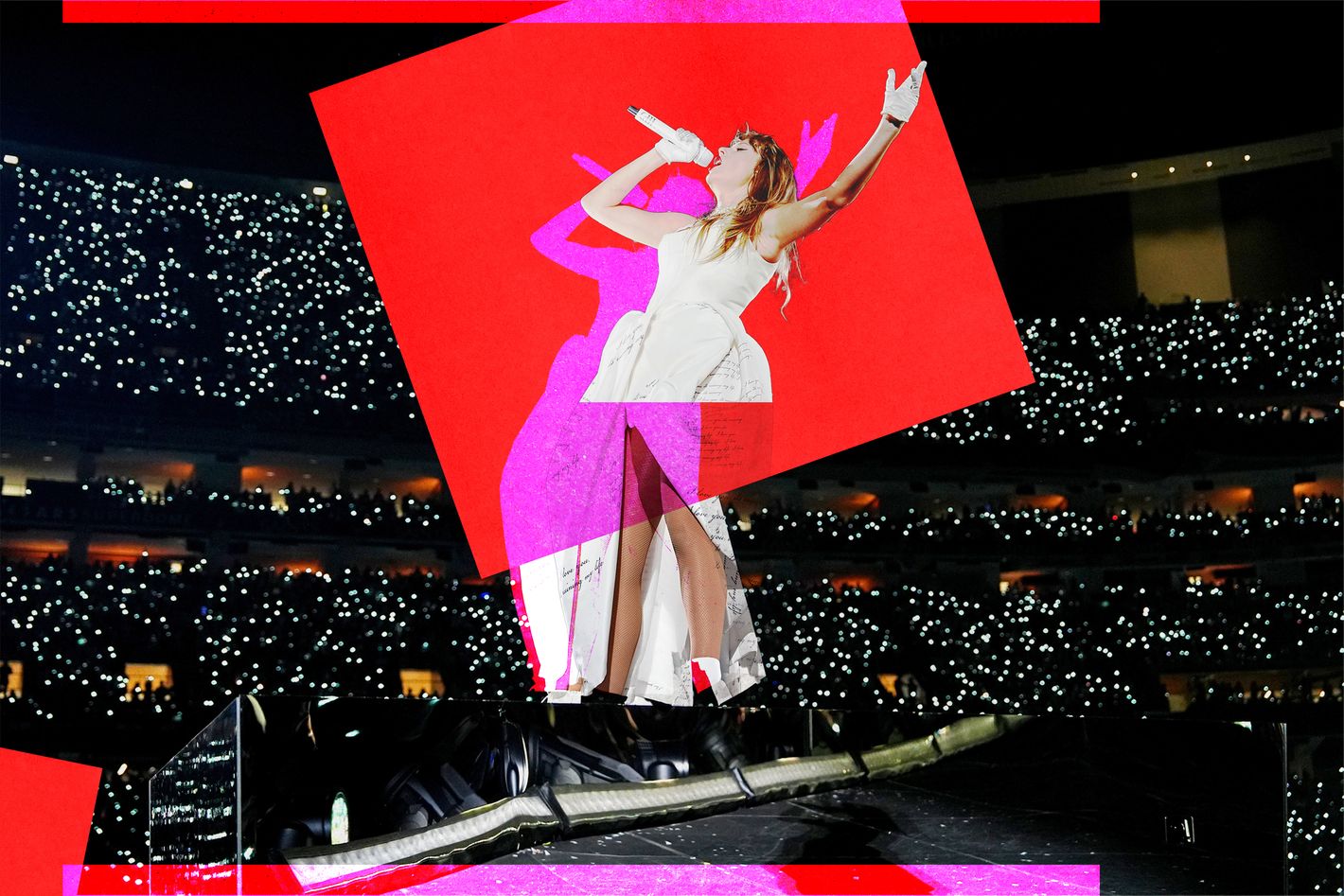

On her 149-stop Eras Tour, Taylor Swift made gigantic stadiums seem impressively small.

The final song played over the speakers before Taylor Swift took the stage every night of the Eras Tour was Dusty Springfield’s cover of the feminist pop anthem “You Don’t Own Me.” From the show’s opening in Arizona in March of 2023 to its final night, on Sunday in Vancouver, a countdown clock filled the screen; the audience screamed, angling their necks to glimpse a celebrity guest or Swift’s mother, Andrea, walking through the crowd; and then Springfield sang, in a voice of mystery, poise, and defiance, for the tens of thousands of attendees, primarily young women:

You don’t own me

Don’t try to change me in any way

You don’t own me

Don’t tie me down ’cause I’d never stay

Lesley Gore first recorded “You Don’t Own Me” in 1963 when she was 17, crystalizing a brooding and self-possessed rebuke to the status-quo subjugation of girlhood. For 60 years, it has become a spectral spell on the social order, a teen girl’s dream of autonomy now pitched to eternity. In Taylor’s own teenage years, she recorded her starmaking 2006 self-titled debut and 2008’s Fearless, whose ownership she has sought to reclaim from male music-biz goons with her ongoing “Taylor’s Version” re-records. “You Don’t Own Me” became a canny epigraph for Eras, gesturing toward Swift’s fight for control of her life’s work and amplifying the tour’s charge of empowerment. It was a magnifying glass over Swift’s evolving mythology.

The explosive phenomenon of the Eras Tour — 51 cities, 149 shows, 10.1 million fans, 18 years of music — made it the most successful concert run in history. It saw masses of “Taylor-gaters” congregating globally; stoked Beatles-caliber mania (neurologists were called upon to explain Swifties’ widespread “post-concert amnesia,” in which fans were forgetting the details due to the sensory overload from their “heightened emotional states”); and, on the first of two nights I attended at MetLife Stadium, at least one leather jacket bedazzled with the instructive “FUCK THE PATRIARCHY.” Yet amid the glittering seas of cowboy boots and Taylor-tailored fits and lyric-driven friendship bracelets (how is the bead industry doing?), and amid the three-and-a-half-hour spectacles of adrenaline that turned private agonies into screamscapes, the 2-billion-dollar-grossing Eras Tour was powered by intimacy.

On one of the biggest stages pop music has known, there was nothing standing between Swift and her audience.

Since her high-school beginnings, Swift has turned the art of compression into her superpower, condensing colossal feelings to handfuls of words evocative enough to be movies but broad enough in which to see yourself: “You made a rebel of a careless man’s careful daughter,” “All of my heroes die all alone,” “We had this big wide city all to ourselves.” Such distillation is a requirement of pop music but often feels like Swift’s only mode. There is no Taylor Swift without a granular commitment to craft, the pinpoint precision with which she clarifies and validates everyday heartbreaks — casual cruelties, canceled plans, the frustrations of being undermined — that the world-at-large might otherwise trivialize. However far Swift’s shrewdness as a businesswoman has taken her — including her recent blockbuster self-released Eras film and official tour book — the secret to understanding the Eras phenomenon is her ability to draw out the secrets in others through the specifics of her songwriting, the emotional details that are the engine behind the enterprise.

When I think of that superpower in action now, I think of “Nothing New.” The Red (Taylor’s Version) “vault” track was not on the permanent setlist. But both nights I attended, Swift was joined onstage by opener Phoebe Bridgers to duet this middle-of-the-night ballad that directly confronts ageism and sexism. Swift wrote “Nothing New” in 2012 on a dulcimer, inspired by how her hero Joni Mitchell authored much of 1971’s Blue, and it accordingly digs deep psychological terrain. The former teen ingénue sings candidly about feeling washed up by her early 20s: “Lord what will become of me / Once I’ve lost my novelty?” To hear Swift unspool this eloquently brutal self-reckoning that she penned at 22 — “Will you still love me when I’m nothing new?” she asks, like the Goffin-King standard recast toward her most enduring love, her audience — at the peak of her popularity, was profound. Swift has described the song’s origins as “my very first brush with the fear of aging, irrelevance, and replacement. How young women are taught by society that our youth is a rapidly depleting commodity.” Eighteen years in, the very conceit of Eras — going album by album to draw a towering portrait of Swift’s catalogue in 44 songs — challenged those cultural ideas while fortifying her place at pop’s apex. “Nothing New” would have been a canonical Swift song in 2012, but today it seems to contain her entire history, the sweep of time, hers and our own.

Swift may have only played “Nothing New” in New Jersey, but on every Eras date, her pair of solo-acoustic “secret songs” contributed to the tour’s growing lore. It showed that Swift could pull out any deep cut from across her catalogue — I saw her strum 2012’s “Holy Ground” and play solo piano takes of 2019’s “False God” and 2014’s “Clean” — and, without the fanfare of dancers or pyrotechnics, let them stand on their own. That three songs this great could be on the cutting-room floor of anyone’s career-spanning set puts into perspective the scale of the mountain Swift finds herself atop in 2024. Her final solo guitar rendition in Vancouver mixed together 2006’s “A Place in This World” (as in, “I’m just a girl / Trying to find a place in this world”) with 2014’s “New Romantics” (“Heartbreak is the national anthem, we sing it proudly”) like her truncated biography. Even the “secret songs” coinage was telling: that, on one of the biggest stages pop music has known, there was nothing standing between Swift and her audience.

The alchemy of Eras came as much from its individual performances as how it staged the whole mythos of her songbook, narrating the arc of her 18-year journey from the twangy infatuations of Fearless to (as she titled the Tortured Poets Department segment in 2024) “Female Rage.” Storytelling is what drew Swift to country music, and she’s been obsessed with the trajectories of the pop greats forever. She was known, on 2011’s Speak Now tour, to scrawl lyrics by Bruce and Neil and Joni, among others, on her arms in Sharpie every night. (As Rob Sheffield writes in his new book Heartbreak Is the National Anthem: “She reinvented pop in the fangirl’s image.”) The strength of her own unprecedented story — her stardom and skill steadily ascending as it approaches its third decade — sets Swift apart in the cultural consciousness. Her lyrics have influenced a generation of pop writers (Sabrina and Olivia among them) and helped create the context for the dominance of female interiority on pop radio today. But the wider-lens narrative of Swift’s catalogue — charting a welcomed unraveling of social myths, moving from the Shakespearean fairytale of 2008’s “Love Story” to the 30-something rejections of marriage on Midnights, which at Eras found an ocean of girls’ screams decimating “this 1950s shit they want from me” — is one that only the accrual of age and years allows. Pop valorizes youth, but aging is what we exchange for the ability to see our past selves with clear eyes.

Among Eras’ aesthetic revelations was how Swift made skyscraping ballads out of songs from her elegant pandemic-era albums Folklore and Evermore — her best work, released at age 30, again defying the sexist stereotype that women artists only age out of relevancy. One of that goth-forest chapter’s heaviest moments is its séance. On “Marjorie,” Swift’s song about her late grandmother, a one-time opera singer, she sung of her “closets of backlogged dreams, and how you left them all to me.” She sings of resurrection and regret. Marjorie’s voice appears at the end of the track, and plays in the show, so when Swift said, “She would have loved to sing at MetLife Stadium,” she manifested that reality. That Swift would conjure the abbreviated dreams of previous generations of women (often on my mind when I think of my own grandmothers) in this monumental setting added a poignant layer that I didn’t see coming. To have this stratospheric artist reach somewhere so personal and unexpected felt like staring into a convex mirror — the kind that warns subjects are closer than they appear.

That felt true observing thousands of young women screaming “When everyone believes ya, what’s that like?” during “The Man,” at the very front of the setlist; when Taylor introduced “Betty” by explaining her fantasy of writing a song that narrates a teenage boy’s rigorous apology to his girlfriend; after the extended outro of “The Archer,” another anthem simmering on unresolved feelings and how the conventions of adulthood can haunt us. The onscreen image of the house from the picture-perfect “Lover” video went up in flames, and when the fire cleared, it gave way to the woods of Evermore, a place to retreat and rebuild again — an unmistakable visual allegory for cycles of personal restoration in the wake of emotional upheaval. These are processes of growth that everyone, even Taylor Swift, ultimately has to go alone. But, more than Swift’s moss-covered piano or ornate gowns or mind-bending dive into the stage each night, more than fireworks or beads, it was those solitary experiences — millions of small stories overlapping with the ones Swift tells in her songs — that brought the spectacle of Eras to life.

That history and electricity were absorbed into Eras Tour’s zenith, the ten-minute version of her opus “All Too Well.” As she strummed the bittersweet opening chords of this sprawling cardiograph ballad at MetLife in 2023, the stadium became a planetarium. This is Swift’s best song, describing the kind of heartbreak that changes you. Whether hearing it from a stadium floor, from 100 rows back, on a grainy livestream, or in a texted video, “All Too Well” is an act of emotional justice. She refuses to allow the trivialization of her memory, which in every line of “All Too Well,” she owns. Really the song is about having agency in your story. At Eras, its gravity was arranged like a dreamscape, the final floating moments seemingly designed to diffuse its pain and send the unflinching details into flight, entering a new memory collectively. “All Too Well” is grounded in the conviction that you know the truth of your experience because you have lived it — that in a rare but eternal moment, you were a witness.

Related