Lola Kirke Tells Us She’s Not Like Other Kirkes

But she is still a Kirke.

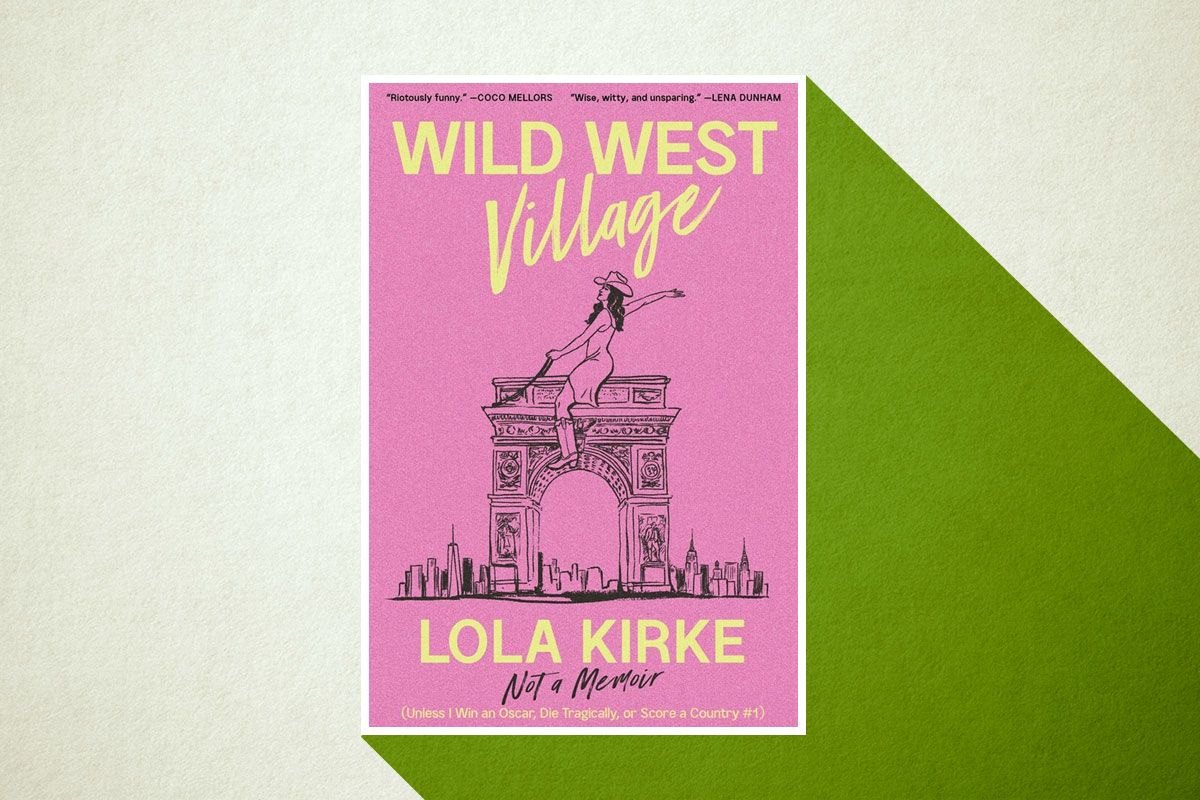

What’s so great about being American? It’s a tricky question to ask in this day and age, but for Lola Kirke, “being American” was representative of everything she wasn’t. The actor and singer, the youngest member of an infamous family that includes actor, painter, and legendary Instagram Stories user Jemima and free-spirited doula Domino, was born into a life few could dream of: rock-star father, socialite mother, West Village brownstone with family connections to the likes of David Bowie and Joan Didion. But name-dropping and seemingly endless wealth does not a happy life make. “For so long, my fantasy of American culture had been the solution to my alienation,” writes Lola Kirke in her new memoir, Wild West Village, out now.

Kirke’s memoir is less coming of age (there’s an argument to be made, perhaps, that none of the Kirke sisters have ever really “grown up”) and more coming of self. While most young people may have to fight tooth and nail to justify pursuing a career in the arts — writing, singing, acting — Kirke grew up in a bohemian environment in which that was expected. “I was raised by wolves,” she writes, but soon clarifies, “these were beautiful, rich, artistic wolves who repurposed vintage nightgowns as party dresses.” She could do anything, literally, though her mother may have scolded her for her occasional inappropriate behavior (older boyfriends, drugs, sneaking out and away). The world was her oyster, lower Manhattan her pearl. A portrait of her naked and smoking as a child hung in the living room of her home, which was “part house, part museum … a bit dysfunctional” and “highly unconventional.”

Kirke paints her family as cruel and obscene and decadent: her mother comes to her for relationship advice, her father has affairs, her sisters — much older — tease and torture her, Jemima especially. It’s clear she loves them. Of Jemima, she writes: “Emi needed me but feared I’d disappear unless I wanted her. Like a monster, this need mostly came out at night … Throughout elementary school, my bedroom door would creak open, revealing the girl who wouldn’t sit next to me on the subway tucking herself into the other side of my bed.” More traumatic than her parents’ separation or child acting attempts was Jemima’s overdose, because of both her sister’s suffering and what it emphasized about her family’s priorities. When her mother calls Kirke to tell her that Jemima is taking herself to rehab, she bursts into tears. “Nothing I ever did was bad enough to make anyone care this much. Nothing I ever did was good enough to make them change,” she writes.

Enjoyment of Wild West Village may be dependent on your tolerance for the Kirkes and their, well, quirks: the free-wheeling careening of a family unbound to money or wealth. Reputation? Don’t overthink it; they certainly aren’t. At one point in the book, nearly every member of the family goes to rehab, a communal experience regarded with more wry detachment than concern. For those who could barely get through Jessa storylines on Girls, 250 pages of these types of adventures may give you a toothache, but Lola is at least a little bit aware of all that. She’s eager to reject a life fated to be chic — instead, she wanted to be an American cliché. “In my mind, Americans were pure and wholesome,” she writes. Kirke longs for summer camp, public school, and the average college experience. But like any youngest sibling, she’s also jealous of what she doesn’t have: a famous boyfriend, an acting career, a drug habit.

Still, Wild West Village lacks the expected gossip of a celebrity memoir, though one particular anecdote about Noah Baumbach on the set of Mistress America lingers in which the director said her skin was so bad it looked like she’d “put a pizza” on her face. Adult Kirke lands on her feet, but far from the hallowed streets of the West Village and instead down in Nashville, where she’s worked steadily as a country singer for the past few years. What is more American, Kirke asks, than a country singer? That world was one that “lived in the voices of long-dead cowboys” she saw on the backs of records and in the songs she learned on her ukulele and banjo. “Country music wasn’t just an escape from my life but a key to understanding it,” she writes. Becoming a musician and writer didn’t give her the opportunity to finally escape her family, but to understand what was so special about it to begin with. The Kirkes have access and wealth and character, sure, but they’re also possessed of a steadfast loyalty to their own amid the chaos. What’s more American than that?

Related