Replacing Halyna Hutchins on Rust Was the Challenge of a Lifetime

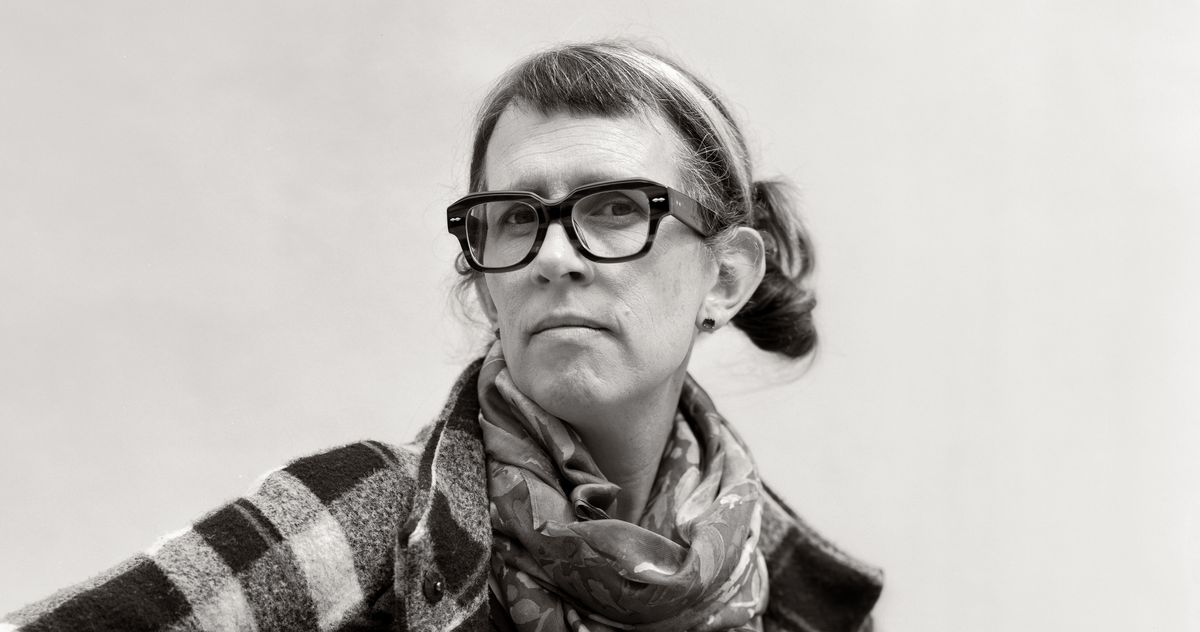

Cinematographer Bianca Cline on why the film had to be finished after her predecessor’s tragic death on set.

When Bianca Cline agreed to step in for Halyna Hutchins, the cinematographer who died of an accidental gunshot wound on the set of Rust, she suspected she might never work again. Still, after careful consideration, she felt it was the right thing to do.

“I hope that the film becomes a memorial to her,” Cline told me over Zoom earlier this month as the Rust crew prepared for the premiere at Poland’s 2024 Camerimage Festival on Wednesday. Although some members of the film community disagreed with the festival’s decision to debut the movie, Cline sees the completed Rust as a potential antidote to a salacious media frenzy — one that allowed the horrific manner of Hutchins’s death to overshadow who she was, both as a person and an artist.

News of Hutchins’s death in October 2021 hit the community hard, and for Cline, the tragedy fell particularly close to home. Beyond sharing an agent and several friends with Hutchins, she had interviewed for the Rust cinematographer role herself. Cline admired Hutchins’s work even before she took over the project; during our interview, she praised her intentional camera movement as well as her gift for using lighting and camera angles to capture anti-hero figures in an empathetic, nonjudgmental manner — a “moving” quality that Cline tried to bring to her own work in Rust.

Now that the film is ready for its debut, Cline hopes viewers can see that no one behind it wants to cover up the senselessness of Hutchins’s death. On the contrary, she said, “I hope people can sit with these two opposing things. Something awful and unnecessary happened, and at the same time, we can watch her work and see how beautiful it is.”

How did the Rust team approach you to help complete the film?

It’s funny, they actually didn’t approach me. I had already read the script and talked to Joel Souza, the director, and I knew the film well. One of my good friends is one of Halyna’s closest friends, and she knew about the project early on because she talked to Halyna’s husband. She called me and said, “They’re going to finish the film, and you’ve got to be the one to do it.” I was kind of taken aback.

Did you agree with that sentiment?

Not at that moment. I was kind of shocked that they were going to finish it. I didn’t quite know why, and I had a lot of questions. But I sat in my room in my apartment for a few days, thinking, Can I do this? Why would I do this? Should I do it? What are the reasons?

How did you ultimately think through that decision?

Like most camerapeople and film people, I was very shocked by Halyna’s death, and I think it hit me especially hard just thinking, That’s where I’d wanted to be. I’d wanted to be there making that movie and then that happened, and so it felt so personal.

Of course.

When it came to whether to finish the film or not, my decision really was, If the tables were turned, I would want her to finish the film. I really try in my life to do everything according to what’s the right thing to do — not what’s easy or popular.

I knew a lot of things about the film, like that the money is not going to the producers, it goes to Halyna’s family, and that her mother and husband want the film to be finished. I know some of her crew members, and I talked to them and they were like, “Yeah, it’s great to be finishing the film for her.” It didn’t make it easy, but I realized this is the right thing for me to do.

What appealed to you about the project itself? Was it the script, the challenge of finishing someone else’s work and flexing a new creative muscle, or something else?

I thought the script was beautiful. Ironically, it’s about an accidental shooting and the aftermath. Even in the original interview, I was thinking, Wow, this is something I could really sink my teeth into. It’s not just entertainment; it’s a heartfelt story, and at the core, it’s really a father-son story.

Joel said to me, “You’re taking on a tall order of having a co–director of photography that you can’t talk to.” But I was very fortunate in that I know Halyna’s gaffer, and he was telling me everything they did — what kind of lamps they were using and what she wanted out of the film. Her camera operator and I talked through what she was doing camera-movement-wise and what she wanted the film to be.

What did that entail?

Joel and I sat for a few days and just watched all the footage they had photographed in New Mexico. I really learned her style. Because the film schedule was pushed, I had probably five months of prep to just sit and watch her footage and think about it. I watched all of her other films and just tried to see, What did she want? What was she trying to accomplish, and what kind of cinematographer is she?

I know that shortly after Halyna’s death, a group of cinematographers released a letter calling for a ban on guns on sets, saying they’ll no longer knowingly work on projects using functional firearms. Did you sign that letter or support its message?

I definitely support that idea. I didn’t sign it at the time because I was mostly just still in shock. I just kind of sat shell-shocked for months, and I was just like, “I don’t really want to even think about those things.” I would sign it today for sure if it still is going around. I think it’s absolutely ridiculous that we use real guns on set ever.

At the time you would have come aboard, I believe the Rust team was still very much in the throes of litigation. Were you worried about how the legal issues would affect the finished product or your ability to do your job?

I was only worried insofar as it would affect us being able to finish it. There were questions about whether Alec Baldwin would be in jail or in court or things like that, which would have inhibited us finishing the film. As far as the legal things that were going on around it, I kind of felt like it was ancillary. It didn’t really have anything to do with us finishing the film.

I think one of the most difficult things for human beings in general is to sit with and accept two opposing things that seem to contradict each other but can exist at the same time. On one hand, yes, it’s tragic. It’s awful. The producers really screwed up — and a bunch of other people, crew members — to result in Halyna’s death. And at the same time, it would be amazing for Halyna and for her family to have the film seen so people can enjoy her art.

Those two don’t need to be mutually exclusive. Just because somebody screwed up doesn’t mean it can’t also be that we can see what she was doing, what she made.

Joel Souza has said he was hesitant to finish Rust until he learned that Halyna’s family wanted to see it finished. What kinds of conversations did you have about the weight of this decision?

Almost every day, Joel would remind me that he’s here for Andros, Halyna’s son. That he’s here to try and help him, because the money goes to Andros, and then he can see what his mother was working on — what she did for, I don’t even want to say living, it’s more than that. It’s a passion, what she loved to do.

That was on everybody’s mind, and we would talk about it a lot — like, all of the crew. We’re here for Halyna. We’re here for Andros. We’re here for Olga, Halyna’s mother. I talked to [Halyna’s husband] Matt [Hutchins] in pre-production to say, “Are you on board with this? Are you okay?” And he was like, “Yes, it’s a great idea. It’s honoring her.”

You’ve mentioned thinking over the potential blowback. What kind of feedback have you gotten? Was it what you expected?

I haven’t gotten a lot of personal attacks. I don’t read comments or go on social media very often, so I don’t really know what’s going on. But people around me have said, “I never see anything about you.” People are kind of angry with the whole thing, the whole idea.

There’s an assumption that the film was finished because producers were like, “Well, we don’t care that a crew member died. We’re going to make money anyway.” And it’s not true. It came from her husband and family, and that’s the reason to finish the film — it’s for Halyna and her family.

What was your first day on set like?

The first day was very solemn in a way. It was intense. Joel gave a very moving speech — which he will not be happy with me mentioning — embarrassed of any praise for himself. But I think he really inspired the crew, inspired everyone. I mean, it was a very unusual show because there were constantly paparazzi around trying to get photographs and really just impeding our production.

After a little while, everybody got a bit used to it. I’m hesitant to say that because, especially in print, it would be like, “Oh, wait, you just forgot about why you were there?” It’s not that. It’s just we also had a job to do. Making any movie is difficult, and this one was especially difficult. The first day was also the first day I met Alec, and we had a good discussion. We were like, “We’re gonna make a movie for Halyna.”

It was in no way a typical production, but at the same time, there were all the typical things we had to do — setting up the camera and photographing and making the day before the sun goes down. It was just extremely emotional. I tried to be very strong and put on a good face and be a good leader and then I would go home every night and just cry. I felt like I was failing Halyna. I felt like I wasn’t doing enough. No matter what I did with the photography, I’m like, That’s not as good as hers.

Putting pressure on yourself to get it perfect.

Having Joel there with me — someone who had stood next to Halyna, someone who was shot at the same time and still coming back — I was like, Oh, I have nothing to complain about. He was going through something much harder than I was.

Did the production have an established road map for finishing? Was this a process of following a template to completion, or did you need to reimagine parts of it?

Joel and I worked really intimately to figure out, “This is what Halyna does. This is what she wants. This is how we’re going to do it.” She had filmed so much of the movie that it was really just a question of matching what she had already done.

The big exception was that Joel wanted nothing to do with the scene in the church, the scene in which Halyna got shot, which was kind of the climax of the film. He rewrote that portion so none of that footage is in it. There’s still an ending, but it’s changed somewhat and definitely in a different location.

That was the only really big change. We changed some of the locations, but other than that, it’s pretty much as it was.

What was your hardest day on set? Do you remember what you were shooting and what made it difficult to capture?

That kind of happened every day, where things we were filming just wrecked me.

Some of the scenes, we would do inserts to replicate certain things. The main character is a 13-year-old boy, so we had a new actor because by that time the other boy was too old. There were scenes Halyna had filmed, and we would just do close-ups of our new boy. Having to re-create exactly what she was doing always got to me.

My very hardest day was actually day 12 because it was the day she died. I think I was the only one who really was thinking of it, and I didn’t really tell anybody, but it was just … [gestures with hands to indicate a heavy feeling around her head] I don’t know how you put that into print, but it’s just awful.

It was awful, but I also had a ton of support from her New Mexico crew; they were aware of how heavy it was but also how cathartic it was for them. A lot of the actors and crew that came back were like, “This gives us some bit of closure. We’re doing something constructive and trying to finish a film for our friend. And that’s beautiful.”

You’ve mentioned your initial conversation with Alec on set that first day. He was accused of being personally responsible for Halyna’s death, though the manslaughter charges were later dropped. This is a pretty unprecedented event for any film production, and especially for a cast and crew to overcome. What was your experience working with Alec through all of this?

I want to preface with something: I hope in the telling of this story, the reason Joel and I really want to do so much press for it, I mean, we debated, I’ll tell you. For a while, it’s like, “We want to do nothing.” We just wanted the film to be all about Halyna. And then we realized, “Well, unfortunately, we’re the ones who have to tell that story.” And so then, we’re like, “Okay, let’s do all the press we can to really just get the story out that we want everyone to hear.”

I really want to shy away from not necessarily Alec as a person or Alec as an actor, but distancing a bit from the tabloid drama — the salaciousness of it. But I will tell you, I think Alec was great to work with for me. He understood that the cinematography was more important on this film than it would have been on a typical film. He was very gracious and helpful to me.

What stood out to you about your last day of filming? Was there a sense of closure? How did it emotionally resonate?

When we wrapped the last day, I noticed something very distinct. The cast and crew that had been in New Mexico were all hugging and crying. All the new crew and cast were celebrating. I kind of felt in between those two. I’m like, Okay, I wasn’t there on set, but also it’s very emotionally heavy for me.

I got to the end of the film and everyone was on set talking and hugging, excited and sad. I ran away. In the back of my mind, I’d thought, I’m gonna get to the end of this film and then things will be okay. And we got to the end, and I was like, But I didn’t do enough for Halyna. I haven’t fixed anything. It was really overwhelming.

In the months afterward, talking to Halyna’s mother more, I realized, Okay, we did do a good thing. It’s just really emotionally taxing, you know? And at the same time that was happening, the new crew was celebrating, as you would with a film. It was so interesting to see both of those opposing feelings occurring in time and both being right and valid.

What are you taking away from this production experience on the whole, and what do you hope viewers take away?

I hope people come away from it knowing Halyna better. I think one of the additional tragedies, aside from the actual, really awful tragedy, is that everyone talks about the horrible way she died, rather than talking about her. Hopefully this will change that a bit. This is not about Alec or awful things that happened to Halyna, but more about looking at her as a person and an artist and trying to appreciate that.

I don’t think I’ll ever do another film as difficult as this one. There may be films that are more logistically challenging or personality-wise something very difficult, but nothing will be as difficult as carrying the weight of trying to live up to the standards of another cinematographer like Halyna.

Rachel Mason, a family friend of Halyna’s, is also working on a film about her with the permission of her husband. I believe you were interviewed for that. What story is that film hoping to tell?

So Rachel is the friend I was talking about earlier. She called me and said, “You have to finish this film.” Rachel wants to do a film about Halyna — what kind of a person she was, what kind of a cinematographer she was, how she lived, how inspiring she is. Her whole life has been a series of difficulties, and she overcame them.

Rachel was on set with us in New Mexico, in Montana — filming, interviewing all the people that were with her before interviewing me and a lot of people who are finishing the film. She wants to show that process and why people were doing it — why anybody would want to do this. I think from a distance, the finishing of the film seems crazy. It’s a bad idea. But when you get in and you really know it and know all the people and all the feelings involved, it seems like the best idea.

I hope Rachel’s film is a companion piece to Rust. It’s like, here’s a great film Halyna made, and here’s all of the “why” and how much effort it took and how nobody did it for the money or for praise.