The Best Film at Sundance Is Just Two People Talking

Ira Sachs’s new film, Peter Hujar’s Day, starts off as an elevation of the quotidian but transforms into something more reflective.

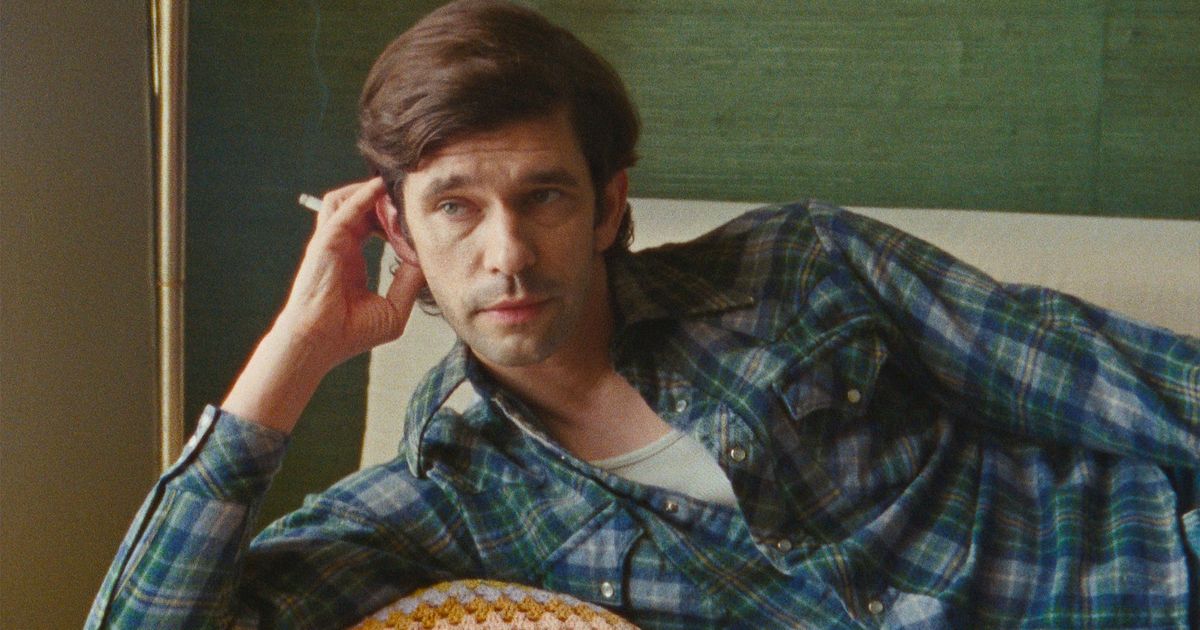

Can a doodle also be a masterpiece? Maybe it’s not fair to call Peter Hujar’s Day a doodle, though Ira Sachs’s film, clocking in at 76 minutes, wears its modesty on its sleeve. Consisting of a conversation between two people in an East Village apartment, filmed austerely but evocatively, the picture revels in its spareness, its warm simplicity. It starts off as an elevation of the quotidian but transforms into something sadder and more reflective.

The film is a re-creation of an interview that happened on December 19, 1974, between the renowned photographer Hujar (Ben Whishaw) and his friend, the journalist Linda Rosenkrantz (Rebecca Hall), who intended their conversation to be part of a book about how different people spent their day. Having taken notes on what he did the day before, Hujar is precise in his accounting, but his fixation on seemingly meaningless details betrays his photographer’s eye. Much of what he talks about is a shoot he was assigned to do with the poet Allen Ginsberg. But other names float through over the course of the conversation — Susan Sontag, William Burroughs, Glenn O’Brien — in that rather New York way, where a conversation between two people usually becomes a conversation about a dozen other people.

It’s not hard to get lost amid all these names and half-anecdotes, but I think that’s also part of the point. Sachs is clearly animated by a love for this long-lost downtown scene, and he conveys it as much through his images and his cutting as he does through the dialogue (which is taken directly from Rosenkrantz’s transcript). As the two talk, they move around different parts of the apartment. They make coffee, they drink tea and eat cookies. They stand outside. They lounge in bed. The light changes. Their outfits change. A shaft of sunlight might hit Hujar in an odd way, the warm glow of a sunset might reflect off a surface. Distant sounds from the street drift in. They touch each other’s legs and heads and feet, glancingly and sensuously, though not sexually. Such sense memories aren’t there to precisely chart Peter Hujar’s path through Linda Rosenkrantz’s apartment. Rather, they evoke sense memories in all of us — we all understand light, and warmth, and the feeling of another person’s touch. It’s through such subtle cues that this tender, lovely film starts to feel like something we might have all experienced once.

Whishaw obviously has to do most of the heavy lifting, dialogue-wise, but Hall is his equal in the way she uses her silences. Her adoration of Hujar comes through, as well as her ease around him. Whishaw gives Hujar’s words a matter-of-fact quality, but there’s a slight hint of melancholy to him, too. He’s filled with anxieties about his art and his work. (The Ginsberg shoot, he says, is his first job for the New York Times.) Hell, he’s filled with anxieties about going four blocks down to another part of the Village. But Whishaw, whose voice is one of modern cinema’s great wonders (there’s a reason why he makes such a good Paddington), conveys the nervousness and the hope and the boredom and the sadness all at once.

Rosenkrantz’s intended book never materialized, but she did publish the Hujar interview as its own volume years later, in 2022, by which point AIDS had long claimed the photographer. So loss is, in a way, built into the very concept of the film. The intimacy draws us in, as if we might know these people. At the same time, we also understand that we’ll never know these people. The maze of names and facts in Hujar’s account, the familiarity he and Rosenkrantz have with each other, the way the setting light captures the ephemerality of this moment, it all feels like something that’s already vanished. We’re watching a mundane spectacle of a mundane spectacle — a man in a room relating the mostly forgettable events of the previous day — but somehow, we’re also witnessing the arc of time within this quiet hour. So, no, the film is maybe not a doodle. There’s too much craft, too much care here for that. But it is a masterpiece.