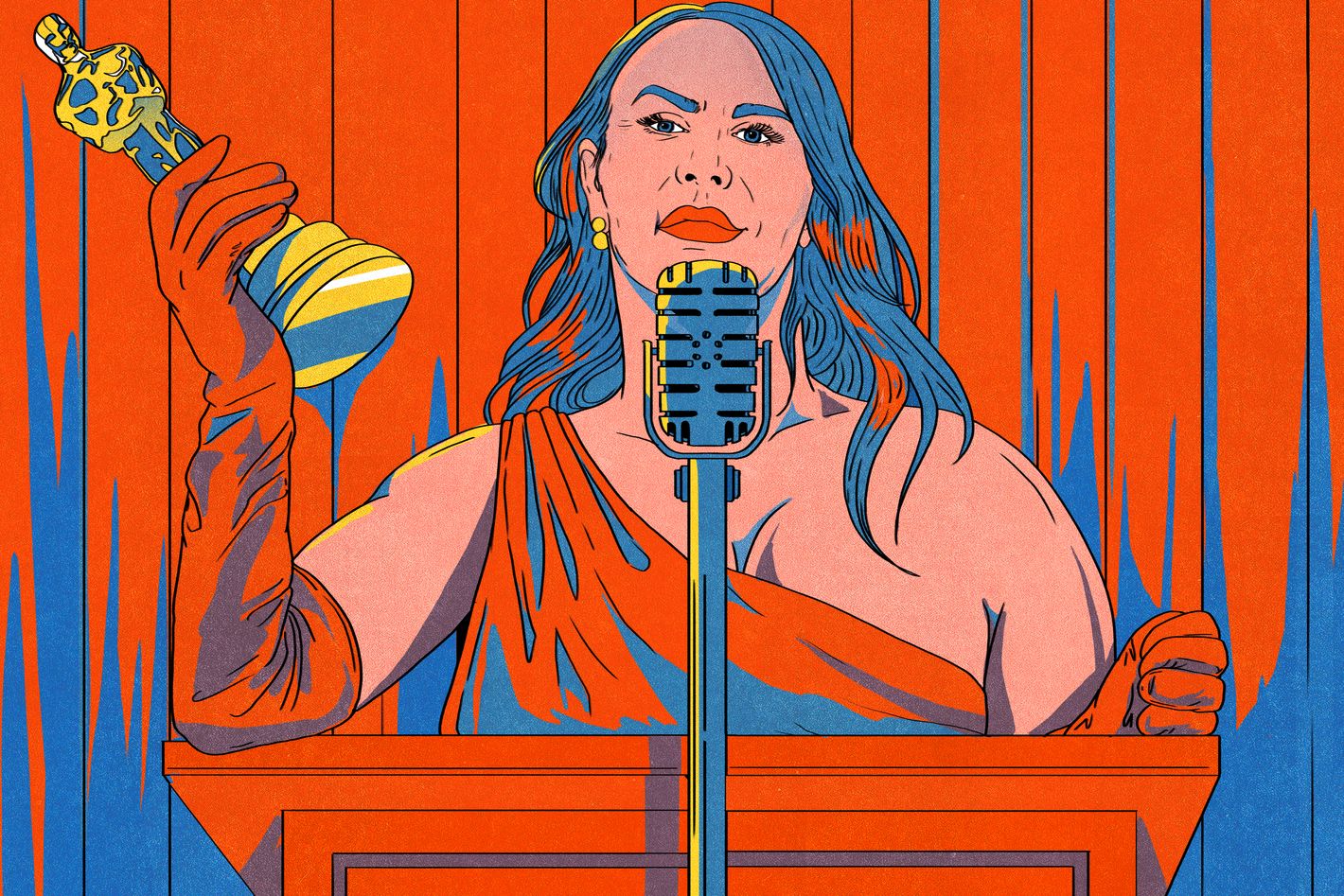

The Making of an All-Time Oscars Villain

How Emilia Pérez — then its star, Karla Sofía Gascón — became this awards season’s most hated nominee.

When this year’s Oscar nominations were announced, one film led the pack: Jacques Audiard’s Emilia Pérez. Its 13 nods were the most for any movie and seemingly thrust it into prime position for the awards season’s final stretch — that is, until old tweets from the film’s star, Karla Sofía Gascón, resurfaced. Whatever Gascón’s range as an actress, the posts demonstrated she had a remarkably comprehensive capacity for bigotry. Muslims and Jews, lesbians, George Floyd, Chinese people, and even the 2021 Oscars ceremony, which featured multiple non-white winners — the Spanish actress disparaged them all. Suddenly, the first out trans actor ever nominated for an Oscar was revealed as the Castilian Clayton Bigsby.

For most movies, becoming the villain of their respective Oscars season is like stepping on a land mine. When La La Land bowed at the Venice International Film Festival in the summer of 2016, few could have anticipated the colorful rom-com would be slammed as “regressive” and a product of white liberal narcissism mere months later. For Emilia Pérez, the villain title felt like its birthright. The film follows a Mexican gangster who secretly transitions, reinvents herself as a philanthropist, then gets embroiled in a family drama reminiscent of Mrs. Doubtfire. It premiered this past May at Cannes, where it won two major prizes and got bought by Netflix, heralding a future as a major awards contender. Reviewers on the Croisette hailed Audiard’s ambition, but even those most onboard could see what was coming: The French musical treated delicate subject matter with the sensitivity and nuance you can expect from the French and from musicals. New York critic Bilge Ebiri called Emilia Pérez “fearless in its ridiculousness” but noted the movie was “filled with giant culture-war booby traps,” predicting viewers would be “yelling at each other about it long after the fest is over.”

That was an understatement. Journalists at Cannes largely sat on the fence regarding Audiard’s handling of trans issues, and as the film left the cosseted festival atmosphere last fall, queer critics began raising alarm bells. Some called Emilia Pérez “a messy, insensitive, often baffling movie that does not seem to understand” its trans heroine; others were content to dub it a “deeply evil monstrosity.” (I should note that I’ve encountered trans people who enjoy the movie and get annoyed when cis writers like me claim the film is unanimously considered transphobic.) Once the film hit Netflix home screens in November, it only took hours for a clip of its most memorable sequence, a Busby Berkeley musical number set in a Thai gender-affirmation clinic, to go viral.

At issue was the film’s conflation of gender transition with moral redemption, dealing with the process on the level of metaphor rather than something undergone by actual people. (In defense, Audiard claimed he had intended the film as an opera, which traditionally has very little to do with actual people.) The director had originally conceived the main character’s sex change as a comedic plot device; it was Gascón who suggested the former cartel kingpin should genuinely suffer from gender dysphoria. For detractors, these origins are evident in the movie’s jarring tonal swings. This is a film, they say, that seems unsure whether it wants the audience to laugh at trans people, celebrate them, or fear them.

While the trans discourse was playing out, Mexican moviegoers were just getting their hands on Emilia Pérez, and they liked what they saw even less. For them, Audiard was the worst Frenchman to hit Mexico since Napoleon III — an auteur who made an entire movie out of his imagined idea of their country, seemingly without consulting a single Mexican. Emilia Pérez’s sins of misrepresentation were legion. The film was shot almost entirely on a soundstage outside Paris. Only one of its five primary actors, Adriana Paz, is from Mexico. Mexican viewers couldn’t help noticing the script was full of awkward transliterations, performed by actors who speak in the accents of other countries or who seem uncomfortable delivering any Spanish dialogue whatsoever. Audiard’s hole was dug even deeper when the community discovered an interview in which he’d called Spanish “a language of modest countries, developing countries, poor people, and migrants.” Eventually, Mexican filmmaker Camila Aurora hit back with the musical parody Johanne Sacreblu, full of ridiculous French stereotypes — perhaps the only good thing to come out of this entire mess.

Still, Emilia Pérez rolled on, winning four Golden Globes and earning nominations at every top Oscar precursor. On the internet, haters echoed Pauline Kael, despairing that they’d never met anyone who actually liked it. As someone who has, I can confirm that they do indeed exist. They are producers, screenwriters, drama teachers; usually over 50, often from outside the U.S. They appreciate Emilia Pérez as a unique and audacious work of art, a big swing that only Audiard, a filmmaker with a knack for emotional extremity, could pull off.

Like its fellow Oscar villains Crash and Green Book, Emilia Pérez fell into the gap between Hollywood liberalism and online liberalism. Up until the moment Gascón’s tweets began making the rounds, its fans considered it the progressive choice in the race. By voting for Emilia Pérez, and nominating Gascón for Best Actress in particular, they felt they were taking a stand against the Trump administration’s efforts to erase transgender identity. Though she was a long shot to win her category, Gascón became the campaign’s ace in the hole. No matter what anyone else said, here was one trans woman who could credibly speak of Emilia Pérez as a beacon of light in the darkness. “You can maybe put us in jail, you can beat us up, but you never can take away our soul,” she said while accepting the film’s Golden Globe for Best Musical or Comedy.

The loss of the film’s progressive halo could prove fatal.

That’s a harder sell now that we know Gascón has espoused views more befitting a Trump Cabinet member. She has called Islam “a hotbed of infection for humanity” and complained about the number of Muslims near her daughter’s school, musing, “Next year instead of English we’ll have to teach Arabic.” She dubbed the COVID-19 vaccine “the Chinese vaccine,” which, “in addition to the mandatory chip, comes with two spring rolls.” She stated that Adolf Hitler “simply had his opinion about Jews.”

What Gascón did next fit the crisis-PR playbook: She put out a statement through Netflix apologizing for the pain her tweets had caused. What she did after that did not. To save her reputation, she embarked on a media blitz — without consulting Netflix or her own publicists — reiterating her apology in incessant social-media statements and interviews, while claiming she was the victim of a “campaign of hate and misinformation.” Various reports say that, in response, the Emilia Pérez campaign has essentially cut off their rogue star. A planned trip to the U.S. has been canceled, and the streamer is reportedly refusing to fund any further travel or styling expenses. Nor have Gascón’s collaborators been kinder. In an interview with Deadline, Audiard washed his hands of his leading lady: “I just don’t understand why she’s continuing to harm us.”

As a sign of how frosty relations have become, Netflix even removed Emilia Pérez from Emilia Pérez. Gascón’s name and image have been scrubbed from the studio’s latest for-your-consideration posters, which do not even mention the movie’s title. Instead, they foreground Zoe Saldaña, who plays the gangster’s lawyer. There’s some irony to this: Saldaña is arguably the movie’s POV character, but she had been controversially slotted in Best Supporting Actress, allowing Netflix to run Gascón as a lead.

The Gascón affair capped off a messy few weeks on the Oscar front. In a competitive field that as many as five films may feel they have a chance to win, the Best Picture race has been marred by a spat of social-media mudslinging. Anora was dinged for its failure to employ an intimacy coordinator, The Brutalist for its decision to use generative AI in the creation of architectural designs. Fernanda Torres, nominated for the Brazilian film I’m Still Here, was revealed to have done blackface in 2008.

In the wake of the Blake Lively-Justin Baldoni drama, it’s tempting to speculate how many of these controversies were seeded by competing awards campaigns. Netflix awards guru Lisa Taback was formerly Harvey Weinstein’s lieutenant, and some see delicious schadenfreude in the streamer’s top contender being taken down by the same methods the disgraced mogul pioneered. However, in the case of Gascón, there’s no mystery to how the racist Tweets resurfaced: They were dug up by Canadian journalist Sarah Hagi, who told Variety she was prompted to look into the actress’s posts after seeing her Tweet the dog-whistle term “Islamist.”

Rather than being organized by shadowy figures behind the scenes, these online narratives are the fruits of a far more chaotic awards-season landscape, full of countless factions operating under their own incentives. Just as politics has turned us all into unpaid surrogates for our favorite candidates, so too do today’s fans take it upon themselves to perform their own opposition research. A bot army loyal to one acting contender can fan the flames of a backlash against his rival. And these new conflicts may have old roots. Before her Tweets resurfaced, Gascón intimated that she was being personally victimized by associates of Torres, by which she may just have meant “Brazilians.” She wasn’t entirely wrong: That famously intense, famously online cohort has joined Mexicans in the battle against Emilia Pérez, striking a blow for Latin America against the European gaze — and maybe winning I’m Still Here the Best International Film trophy in the process.

If all this controversy has indeed capsized Emilia Pérez’s Oscar hopes, it may take a while for it to sink in. In the case of the influential Producers Guild Awards, voting ended the exact day the scandal broke. But Academy members will have ample time to process everything: Final voting for the Oscars begins on February 11. The few Emilia Pérez fans who are willing to speak say (anonymously) that their own opinions are unaffected, but on a ranked-choice ballot that tends to reward consensus, the loss of the film’s progressive halo could prove fatal. For the moment, we must consider Emilia Pérez a zombie contender, shuffling along the Oscar pole dance dead and yet undead.