The National Book Foundation’s New ‘5 Under 35’ Is Here

From a heady tale of non-monogamy to a haunted voice assistant, this year’s nominees confront a changing world.

Every year, the National Book Foundation announces its roster of five writers under the age of 35 whose debut work of fiction “promises to leave a lasting impression on the literary landscape.” Once again, Vulture is excited to reveal the honorees, each of whom was selected by an author who has been previously honored by the foundation. “We have no doubt that the 2025 ‘5 Under 35’ honorees will similarly continue to shape contemporary fiction, and it is our honor to champion their boundless potential and talent,” said David Steinberger, chair of the board of directors at the National Book Foundation.

These young people write about loneliness and love, family ties and polyamory, contemporary life on the Navajo Nation, and a father-son duo intent on saving a failing firearms store in Arizona. Their short stories and novels confront a changing world where globalization and technology may threaten to blot out our inherent humanism. They’re funny, tender, and urgently told; one of them is written in rhyme. Read on to find out more about each of the books selected, from a short-story collection that upends expectations for Native American fiction to a novel that George Saunders said gave him “a new sense of interest in the world.”

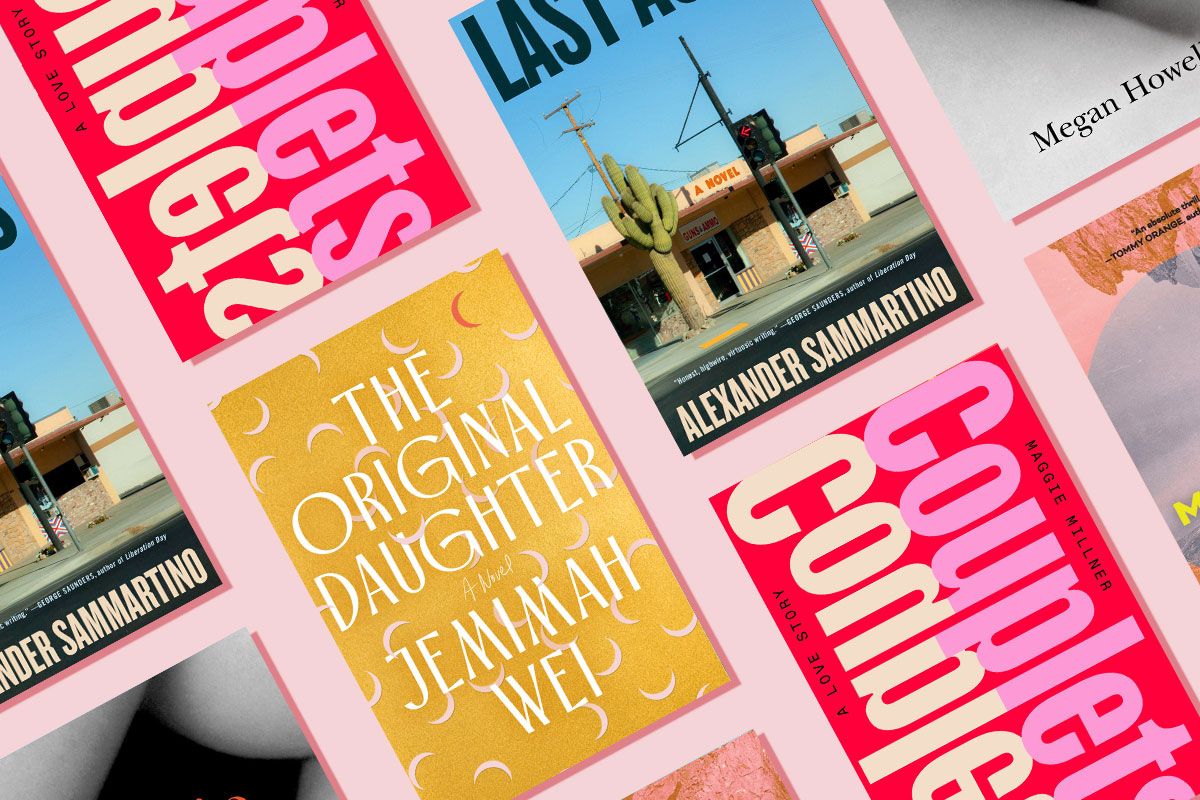

Stacie Shannon Denetsosie, The Missing Morningstar and Other Stories

Synopsis: In these stories, many set in and near the town of Kayenta on the Navajo Nation, children struggle to understand the soft core of their mothers’ harsh love, a Diné teenager decides what to do when she learns she might be pregnant after a liaison with a white man, and a woman’s Amazon Alexa speaks to her with the voice of her deceased mother. Denetsosie’s work is sharp-eyed about the lasting impact of American colonialism on Native communities and the seismic shifts that contemporary life has brought.

Denetsosie on experimentation: “I did a master’s program in literature and creative writing at Utah State, and then I did one in fiction at the Institute of American Indian Arts. The title story of this collection I wrote while I was at Utah State, and for me, it mostly was not a meditation on what it means to be Native American. I was writing at a PWI [predominantly white institution], so a lot of my workshopmates were non-Native, and it was interesting to see people’s ideas and opinions about what they think Native American literature should be. Native American literature has a cinematic quality to nonnative readers — people expect the noble savage, or they expect a Pocahantos-type story. When my stories were women-led and had queer characters, I think it really surprised a lot of my classmates, and I think that it was for the better. The stories I wrote at the Institute of American Indian Arts were more of an exploration of our identity through time. It was such an honor to be more experimental and step away from this tight authorial custody that I had over my work previously because I didn’t want anybody to misconstrue anything. One of my mentors, Kristiana Kahakauwila, told me, ‘You can release some of that, and you can trust your reader a little bit more.’ Hearing that as a writer was really, really liberating.”

Selected by: Mona Susan Power, 2023 National Book Award Longlister

Power picked it because: “I know I’m in the hands of a superb writer when my world drops away and I wholly surrender to their voice and vision. The Missing Morningstar knocked me out from the start. These stories pop with intense, brilliant energy — the well-crafted prose alternately poetic and stark, painting unforgettable scenes in striking detail. Denetsosie’s vivid, complex Diné characters claim space in a world that often ignores their truth. This collection is a confident storm of stories that need telling. I’m so grateful for the debut work of this blazing talent.”

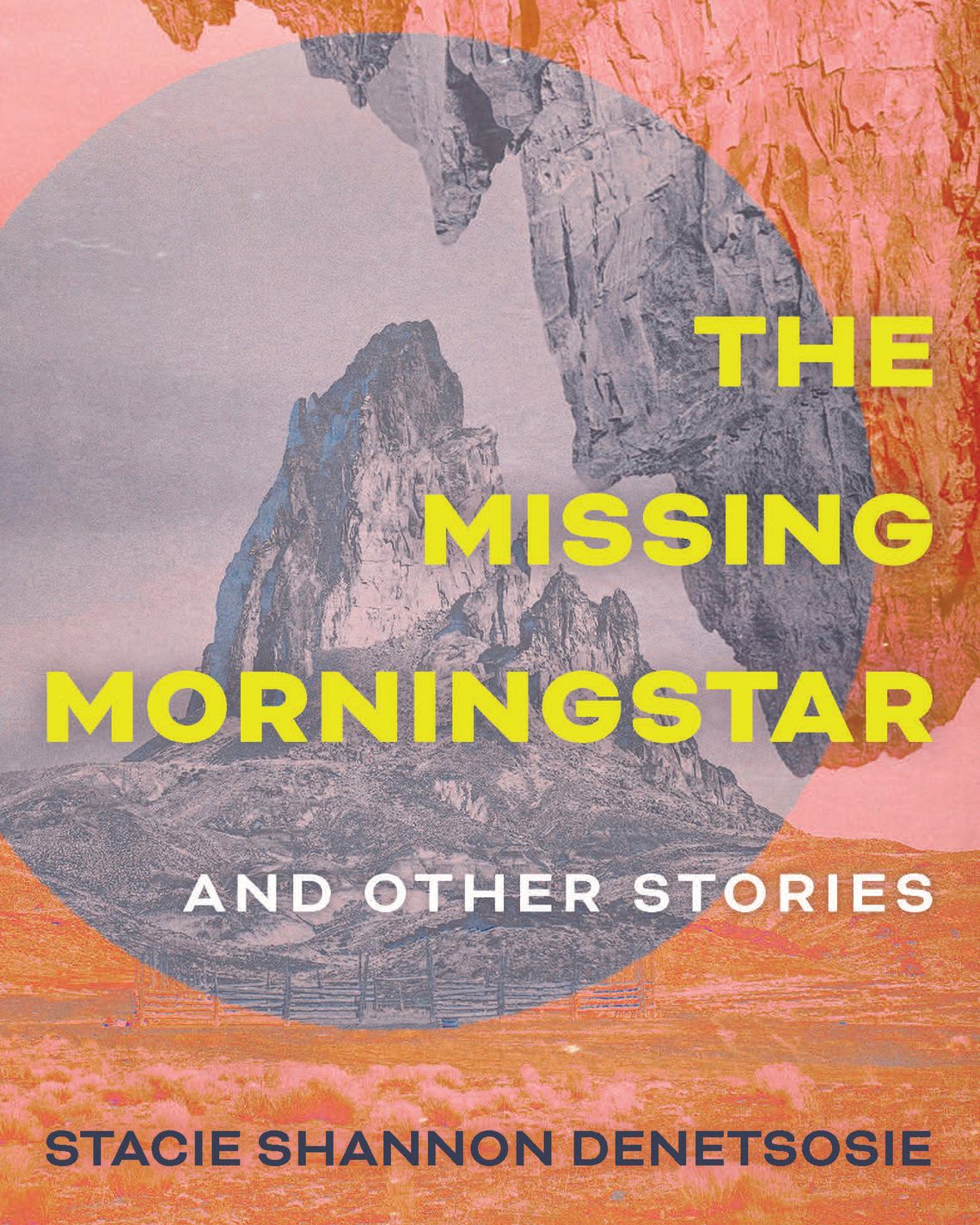

Megan Howell, Softie

Synopsis: A narrator lusts after her lover’s earlobes. A hotel houses a collection of lonely drifters. A middle-aged woman goes overboard with a bottle of “Age-Defying Bubble Bath,” which turns her into a child again. The characters in Megan Howell’s short stories, which glide into scenes of magical realism, are lonely people facing the harsh realities of an often violent world and fumbling toward something more hopeful.

Howell on vulnerability: “I wanted to have characters who are at their wits’ end to the point where they have to reveal everything, because their lives are about to fall apart. People who are very much in the thick of it and can’t pretend like nothing is happening. Their lives are centered around people who hate them or situations that are just destroying them internally. They have to be vulnerable in their stories — otherwise they would be hiding their entire lives. It became apparent as I was writing this collection that the themes of cruelty and relational aggression were really big. From there, I came up with the title Softie — this idea of being very sensitive, even as an adult; of maintaining a softness even though the world can be hard and difficult and the expectation is that you harden yourself.”

Selected by: Deesha Philyaw, 2020 National Book Award Finalist

Philyaw chose it because: “I was introduced to Megan’s collection via a glowing review by Hannah Grieco in Washington City Paper. There was one line in particular that grabbed me: ‘These are not stories about race or gender or oppression. These are stories about people living in a world that punishes them.’ ‘Punishing’ is exactly how the world feels right now, exactly how I feel living in it right now. So not surprisingly, I found myself nodding and gasping as I read the stories, even the magical and surreal ones, because Megan so beautifully captures the heart going through the ringer while trying to survive. Megan writes with a rare fearlessness and nimbleness on the page. She’s not beholden to narrow notions of what makes a work ‘literary,’ if she’s thinking about such things at all. With the stories in Softie, she’s created a new lane in which ferocity and tenderness co-exist in smart, seamlessly crafted narratives. Softie is an inspiration for every writer who has been misled to believe their work has to fit in certain conventional boxes to be excellent.”

Maggie Millner, Couplets: A Love Story

Synopsis: A narrator in a happy, steadfast relationship with a man finds herself falling in love again, this time with a woman she meets at a bar. Her “second adolescence” reframes everything she thinks she knows in ways both painful and delightful. This cheerfully genre-crossing autobiographical novel is told in rhyming couplets with some prose sections interspersed.

Millner on couplets and polyamory: “There’s a natural conversation happening between the form, which is a kind of dyadic couplet form, and ideas about relationships and how many people can belong inside them. Part of what the book is about is how when you have a formative relationship, even if you go on to date other people, you’re so intensely shaped by that relationship that you don’t stop being in relation to that person. There’s a way that your new partner is dating that other person because they’ve made this totally indelible impression on who you are. I don’t think Couplets is a pro-polyamory book, but I think it’s a book that is wrestling with the fact that there are never just two people in a relationship anyway, because we live really social lives and we’re formed by the relationships we’ve been in. We want to be connected in all kinds of ways to other people. Also, we’re creatures — at least the narrator of this book is, and and I think many other people are too — whose psychology is such that when you impose a really hard-and-fast rule, some kind of curiosity necessarily emerges about how it would feel to break that rule or transgress that convention.”

Selected by: C Pam Zhang, 2020 “5 Under 35” Honoree

Zhang chose it because: “These words cut to the hot quick of longing; these pages bleed beauty. Tender, prickly, funny, self-effacing, cerebral, erotic, and luminous, this is a book that never settles, forever restless, an ode to that deepest and most abiding form of love — that for one’s many infinite selves.”

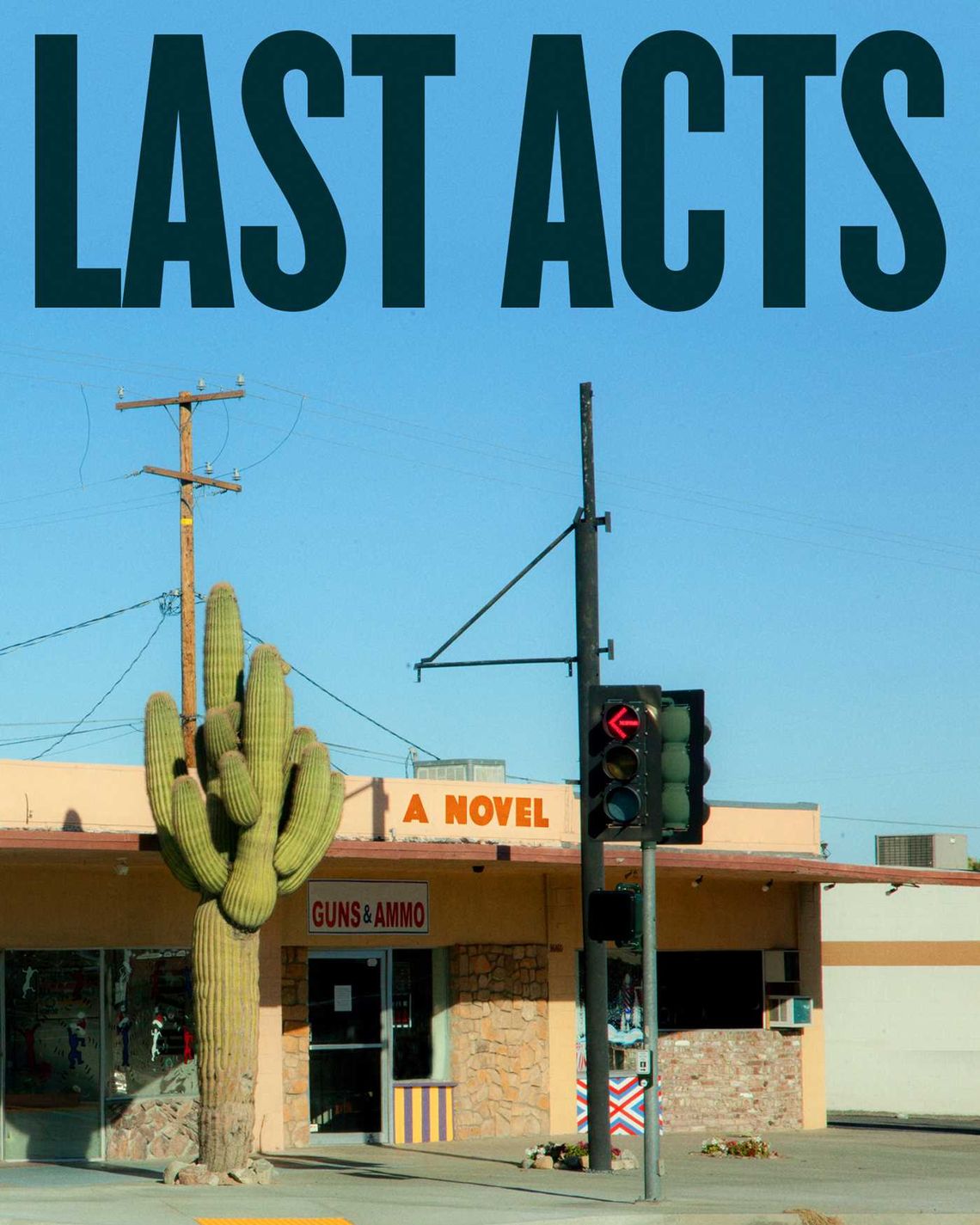

Alexander Sammartino, Last Acts

Synopsis: David Rizzo’s firearms store is close to foreclosure after a series of failed moneymaking schemes. When his estranged son, Nick, calls him from the hospital after a heroin overdose, the two decide to team up to save the business — after all, they each have nowhere else to turn. Sammartino’s debut novel, set in Arizona, has a keen sense for the ludicrous details of 21st-century American life and the sadness thrumming just underneath.

Sammartino on writing a novel while working a full-time job: “While I was writing the book, I was working in software sales, and I was thinking a lot about the salesperson and the lifestyle that entails, the relentless optimism and delusional ambition and how that can lead to some horrific consequences. When I started that job, it was before COVID. I woke up at 4:30 every day. Wrote before work, went to work. I would come home at night and try to write some more. Then COVID happened, and working from home made it a lot easier to get work done. It was this interesting thing where it made the writing really exciting, because I got to do it. It was outside of work, so it really felt like something very playful and something special that was mine.”

Selected by: George Saunders, 2013 National Book Award Finalist

Saunders chose it because: “What really drew me into Last Acts, from the very first pages, was a certain quality of warmth and confidence — a sense that the writer was genuinely interested in the world, just as it was, and wasn’t afraid of anything he might find there. So, a sense of wry wonder that manifested as a pretty rare thing in fiction these days: genuine humor. Sammartino has gone into a world largely neglected by literary fiction and just lit it up with his wit and curiosity.

The book does that thing literature does, which is welcome us into a world we might not know anything about and then reassure us that the rules of life we live by operate in that place as well, albeit morphed by particularity. In Last Acts, for me anyway, this had the effect of reassuring me — it made me feel a new sense of interest in the world and particularly in the precise nature of our American dysfunction.”

Jemimah Wei, The Original Daughter

Synopsis: Sisters Genevieve and Arin, raised in a tiny apartment in Singapore with an unhappy grandmother and two struggling parents, are used to taking solace in each other’s company. Dedicated to achievement at all costs, they strive to rely only on themselves — until a devastating estrangement wrenches them apart. This novel’s central sibling dynamic, shaped by the rapid social changes happening around them, is stunning in its depth.

Wei on writing about Singapore: “Growing up in Singapore, especially at the turn of the millennium, I was constantly aware of life’s velocity, this feeling that the world was simultaneously accelerating and becoming nostalgia-tinged before our eyes. So writing this book has felt, in some way, like a furious documentation of a disappearing world, a way to resist waking up one day into a totally unrecognizable reality, advanced beyond our wildest imaginations yet with our personal histories and quiet joys lost to the unreliability of memory. That’s why it was so important to me to get the stuff of living — the tiny fauna, the French fries and noodles, the things that wouldn’t make it into official narratives — down. I didn’t really think about audience; it was more about being able to say, ‘We were here, we existed, this was what it was like.’ Having that world immortalized in print means a lot to me.”

Selected by: Morgan Talty, 2023 “5 Under 35” Honoree

Talty chose it because: “I like books that transgress against the western arc of narrative. Jemimah plays into that narrative but uses it to her advantage, to resist a lot of the tempting selling points, so to speak, of the novel while still making it super-satisfying. I think books are meant to heal us, but they’re also meant to break us. Jemimah’s novel doesn’t really have a sense of resolution to it in a typical or traditional way. It lingers like a cut does — one that doesn’t fester or get infected, but that’s always kind of there. That’s just what The Original Daughter does, from every single word, from diction to syntax to plot and voice to character and even theme. There’s an element of transcendence to this book that’s hard to come by.”

Related