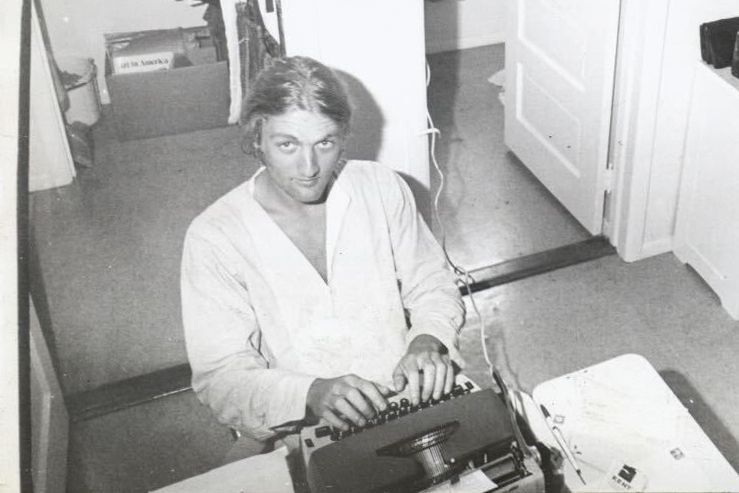

Walter Robinson, Rogue Pirate of the Art World

The longtime man-about-downtown died this week at age 74.

Going to art shows with Walter Robinson, the artist, writer, and human bullshit detector who died earlier this week at age 74, was like walking around with an oracle. He always had insightful, surprising, arch things to say. “I learned more in one day with Walter than two degrees at Oxford,” the writer Ana Finel Honigman told me. A beloved fixture of the art world since the early 1970s, he wore his eminence lightly, always carrying a book bag, giving his love in sly ways, and leaving you dazzled, off-balance, and wanting more.

A polymath, he wore many hats. Between 1973 and 1978, he irregularly published the downtown magazine Art-Rite with compadres Edit deAk and Joshua Cohen. Covers were by artists like Christo, Pat Steir, Ed Ruscha, Dorothea Rockburne, Robert Ryman, and Vito Acconci. In 1976, he co-founded the art bookstore Printed Matter, which still operates today. In 1977, he founded the downtown collective Collaborative Projects with Kiki Smith, Jane Dickson, Joe Lewis, Diego Cortez, Jenny Holzer, Tom Otterness, and many others. Colab, as it’s known, was against minimalism. (People used to define themselves by what they were against.) When I moved to New York in 1980, Colab was the DIY art world I wanted to be a part of. These were the cool kids and hipsters, the desperate and burned out, the visionaries and druggies. Us!

I met Walter when I began writing for Art in America in the early 1990s. We used to hang out in his small, cluttered office, laughing, talking, avoiding writing. He had a million interests and contrary opinions, an outlaw pirate. Around this time, he had an access-television cable show in which he and two pals went into galleries and talked about what was on view. They were often thrown out.

Between 1996 and 2012, he was the online editor-in-chief of Artnet. As soon as my first Village Voice column came out in 1998, he asked if he could republish whatever I wrote on Artnet. I said “yes” without checking with my bosses and never looked back. This was a game changer for me. It made me realize that writing did not exist if it did not exist online. At Artnet, Walter assembled a motley crew of writers, including the unstoppable Charlie Finch, who would meanly attack everyone. Including me! A lot! I remember begging Walter to not publish his diatribes about me. He laughed and said, “I can’t stop him.” He made me realize that writers should just shine on like crazy diamonds.

Walter was a great writer. He had a weekly Artnet column called “Weekend Update” in which, in almost stream-of-consciousness prose, he’d riff on everything he saw and all the openings and parties he went to. His observations were based in theory, intuition, inquisitiveness, and his penchant for saying things others were scared to say. I felt jealous when, in 2014, he published a defining essay on what he brilliantly called “Zombie Formalism,” his term for the modern craze for abstract works “that function well in the realm of high-end, hypercontemporary interior design.” The name stuck. How many critics have named a movement?

Walter was also an artist. A good one. Like Andy Warhol, he painted things he liked: women, vixens, beer, scenes from films, pulp-fiction book covers, hamburgers. He once gave me a watercolor of a BLT. Long before Damien Hirst cashed in making them, Walter made spin paintings. My wife has one that hangs in our home. His style was loose, colorful, and brushy. Curator Barry Blinderman calls him one of the “most underrated, unknown, undervalued” artists.

After he lost his job at Artnet, he returned to being a full-time artist. With his wife, Lisa Rosen, he became his version of happy. He asked people to visit him in his studio. Whenever he appeared at museum press previews, other critics gathered around him, probing him for his opinion, and he was always mischievous and cagey about giving it. Yet what Walter thought and felt about art was somehow always with us anyway.