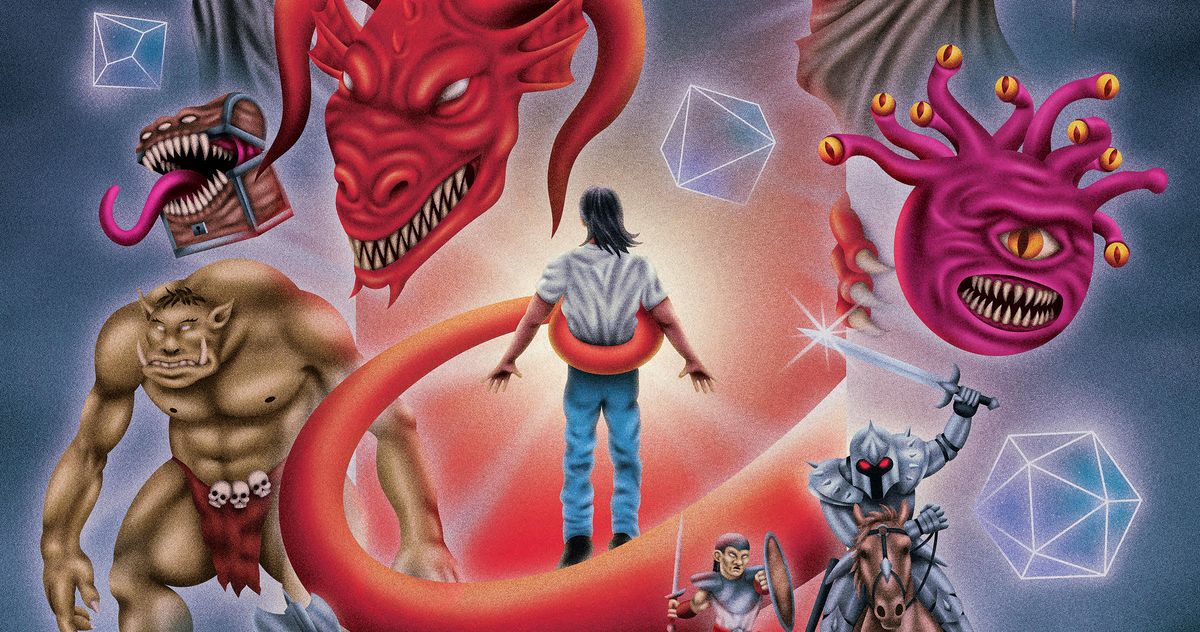

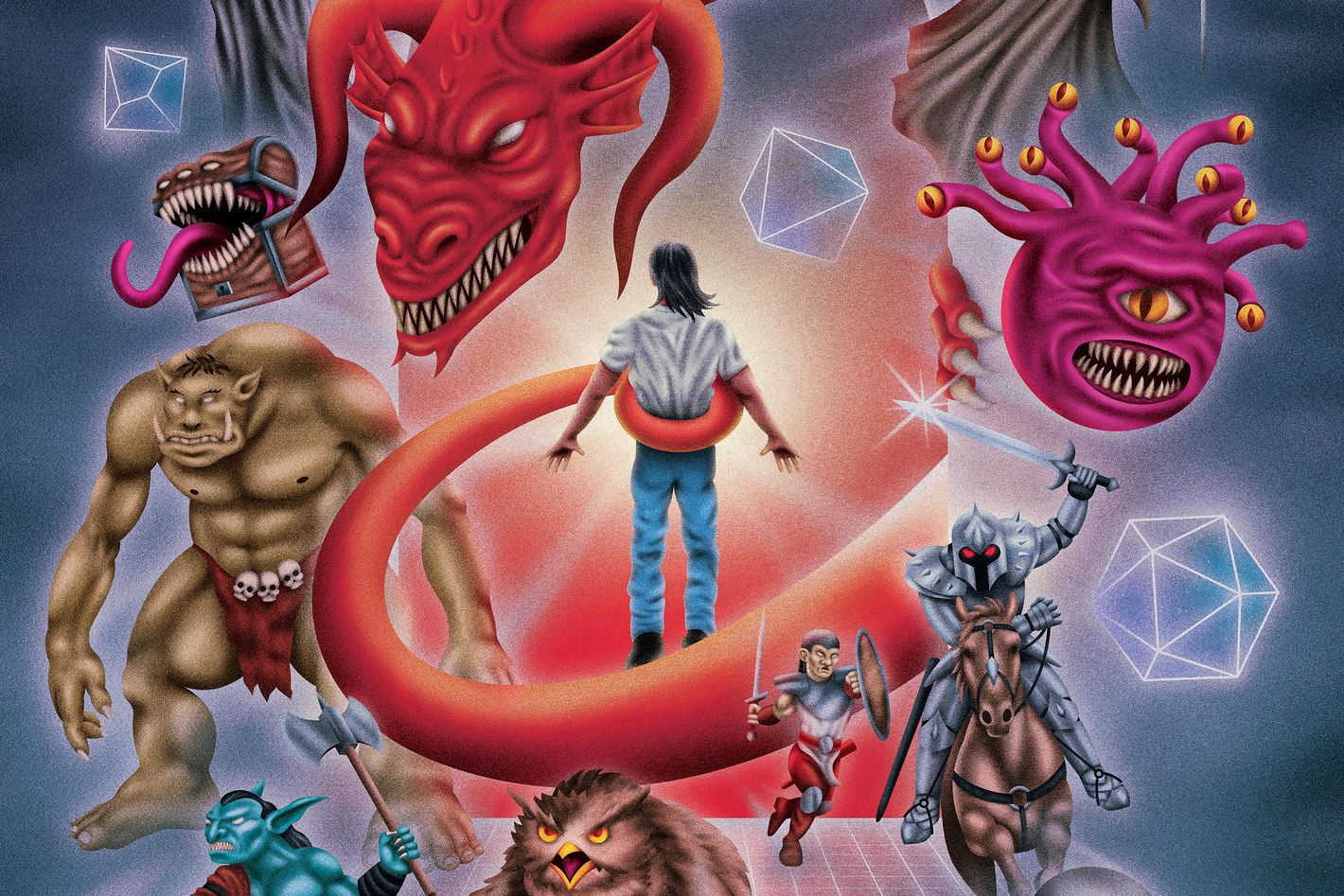

Why Is ‘Dungeons & Dragons’ So Misunderstood?

At 50, the game is more popular than ever, but its core appeal is still a great secret.

In the summer of 1979, the New York Times reported that a 16-year-old student at Michigan State University named James Dallas Egbert III had gone missing while playing a “bizarre intellectual game.” In his dorm room, campus police had discovered a suicide note as well as a corkboard covered in thumbtacks that seemed to map out the school’s underground steam tunnels. From the boy’s mother, police learned that Dallas had recently developed an interest in a game in which players assumed the roles of fantastical heroes who slew monsters and uncovered lost treasures through a combination of dice rolls and make-believe. The cops initially mistook the game for a local cult; in fact, it was published by a tiny company called Tactical Studies Rules, or TSR, operating out of a dilapidated hotel in Wisconsin. Before long, the Egbert family’s private detective was speculating that the game had caused Dallas to “slip through the fragile barrier between reality and fantasy.”

The reality was, as reality tends to be, less fantastic: Dallas had entered the tunnels meaning to kill himself with quaaludes. Having survived, he ran away to Louisiana, where he resurfaced a month later. At most, his interest in entering an imaginary world may have been an expression of the intense feelings of alienation that came with being a child prodigy and, apparently, a young gay man. (He committed suicide with a handgun the following year.) But the game, called Dungeons & Dragons, had already captured the imagination of an American public increasingly fearful of — and fascinated by — the prospect of brainwashing, organized cults, and devil worship. The religious right called the game evil. TSR couldn’t keep up with demand.

This year, Dungeons & Dragons celebrated its 50th anniversary. Some 50 million people have played the game, according to its publisher. Women now make up nearly 40 percent of players; queer people are almost certainly overrepresented, as they are in video gaming. The game’s influence on the latter is vast: Concepts like hit points, character classes, and leveling up all originate with D&D, as does the much-memed alignment chart that categorizes items from good to evil and lawful to chaotic. The game’s current popularity is partly an effect of the pandemic, when many first-time players hopped on five-hour video calls that filled the deserted halls of lockdown with displacer beasts, mind flayers, and the dreaded gelatinous cube. (I was one of them; I currently act as dungeon master for two campaigns.) A thoroughly decent D&D film, starring Chris Pine as a hapless bard, appeared in 2023. The past decade has also seen the rise of “actual play” shows like Critical Role and Dimension 20, where actors, comedians, and gamers participate in original, well-produced campaigns with catchy premises. A live version of the latter show, coming in January, sold out Madison Square Garden. The bizarre intellectual game, it seems, has finally gone mainstream.

Still, D&D has never quite resolved its relationship to reality. During the satanic panic of the ’80s, the game’s publishers stressed that D&D was a harmless leisure activity enjoyed by productive members of society — like reading a novel, only better. “This is a game that is fun,” a 1982 rule book amusingly stated. “You, along with your friends, will create a great fantasy story, you will put it away after each game, and go back to school or work, but — like a book — the adventure will wait.” Yet unlike a novel, a D&D campaign had no fixed ending; in fact, the game’s uncanny way of resisting all attempts to end it, like Scheherazade delaying her execution with yet another tale, was both a selling point and a real source of anxiety. “Game players often joke that they are ‘crazy’ or ‘insane,’ ” wrote the sociologist Gary Alan Fine in his 1983 study, Shared Fantasy, noting the community’s awareness of a “relation between psychosis and immersion in a fantasy world.” Early D&D media reflects this: Andre Norton’s 1978 novel, Quag Keep, the first book ever set in a D&D universe, concerned a group of players who are sucked into a fantasy world — and make peace with staying. A darker vision of the game would appear in the delightfully overwrought made-for-TV movie Mazes and Monsters, starring an unknown Tom Hanks as a delusional role-player who tries to jump off one of the Twin Towers and ends up in a permanent state of psychosis.

In truth, one never forgets one is playing a game. Engrossment may be the goal, wrote Fine, but it is never “total or continuous.” One’s visits to the fantasy world are constantly interrupted by the rolling of dice and the adjudication of rules and, above all, by the players themselves, whose active role in inventing that world unavoidably reveals it, again and again, as totally invented. For this reason, D&D could never offer the kind of deep immersion achieved by the best fantasy novels. But it’s the constant thwarting of immersion that engrosses players most of all. After all, players are not readers, no matter how absorbed they are; nor are they writers, no matter how creative they are. They are more like the children of Tolstoy’s Childhood, whose reenactments of adventure novels are spoiled by an older boy who smugly points out they are just pretending. The difference is that players are also like the older boy; they have access to both the pleasure of entering a made-up world and the pleasure of knowing they are the ones making it up. This is the great secret of the game: not that it lets players become other people but that, by reflecting the force of their own imagination, it affirms the people they already are.

The desire to visit an enchanted world of the sort one might read about in books probably dates to the early 17th century. The moony hidalgo of Don Quixote spends so much time poring over popular chivalric romances — forebears of the fantasy novel that featured magic swords, evil wizards, and fire-breathing dragons — that he comes to regard them as factual accounts. Thus inspired, he creates a heroic persona, dons his starting equipment, and rides out in search of experience points; at his side is his sensible squire, Sancho Panza, always trying to pull him back down to reality. Mark Twain would later write that Cervantes, by means of his ridiculous knight-errant, had single-handedly “swept the world’s admiration for the mediaeval chivalry-silliness out of existence.” But Don Quixote, which is often called the first modern novel, could not decisively break from the chivalric tradition without affirming its very real power to ensorcel the reader. When Quixote’s friends decide to burn his book collection, his housekeeper worries that one of the many sorcerers contained therein will “bewitch us in revenge for our design of banishing them from the world.” The local curate thinks her naïve, but she is simply giving voice to an implicit fear that books about magical worlds may as well be magical themselves.

We might say, then, that the novel was born of an attempt to take the witchcraft out of reading — or at least to reform any lingering witches. Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, as part of its famous defense of the realist novel, would concern an avid reader of Gothic romances whose diet of haunted castles leads her into a “voluntary, self-created delusion” that later mortifies her. Likewise, a young Charlotte Brontë would bid farewell to the beloved fantasy nation of Angria she and her brother had created as teenagers. “I long to quit for a while that burning clime where we have sojourned too long,” she wrote in 1839, nearly a decade before Jane Eyre. “The mind would cease from excitement and turn now to a cooler region, where the dawn breaks grey and sober.” Yet the flame of immersive fiction, as the scholar Gerald Nachtwey writes, would burn brightly all through the 19th century — from the exotic imaginary landscapes of Romantic poetry to the gripping entertainments of the adventure novel. Robert Louis Stevenson, author of Treasure Island, argued in 1882 that romances alone could satisfy the “nameless longings of the reader” for striking incidents and fantastical visions. “In anything fit to be called by the name of reading, the process itself should be absorbing and voluptuous,” Stevenson asserted. “Then we forget the characters; then we push the hero aside; then we plunge into the tale in our own person and bathe in fresh experience.”

By the 20th century, the fantasy novel as we now understand it had begun to take form. The rise of the pulp magazine would provide a home for the “weird fiction” of H. P. Lovecraft and the “sword and sorcery” of Robert E. Howard — stories of mighty barbarians and tentacle monsters stitched together from everything that had to be cut out of the serious novel in order to keep it serious. As Jamie Williamson has detailed, many of these pulp stories, along with some late-Victorian fairy tales, would later be collected and reprinted by Ballantine Books following the wild popularity of its 1965 edition of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, easily the most influential fantasy novel of all time. Lin Carter, editor of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series, would claim that the “mania” of fantasy readers was unsurpassed. “I believe that a hunger for the fabulous is something common to the human condition,” he wrote in his study of the genre, Imaginary Worlds. “To be a human being is to possess the capacity to dream; and few of us are so degraded or brutalized that we have no thirst for miracles.” For Carter, the fantasy novel was a distillate of readerly desire: not just the desire to read about strange worlds and exotic beings but the desire to return to the “original form of narrative literature itself.”

The Ballantine series ended in 1973. The next year, Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson published Dungeons & Dragons. Gygax, a laid-off insurance underwriter in Wisconsin, had previously worked on a medieval-themed war game called Chainmail. Its rule set had included a brief “fantasy supplement,” encouraging players to “refight the epic struggles related by J.R.R. Tolkien, Robert E. Howard and other fantasy writers” — or else devise their own “world.” One such player was Arneson, a recent college grad living with his parents in Minnesota, who began running a heavily modified campaign about a group of feudal lords charged with protecting their fiefdoms from invading armies. Between battles, Arneson gave his players the option of exploring dungeons to fight monsters and find magical treasures, while he himself took on the unusual role of “referee.” Before long, players had gotten so absorbed in dungeon delving they began to neglect the defense of the realm. “Well, all that running around in the dungeons finally got the castle wiped out while our flock of heroes went looking for adventure and treasure,” Arneson drolly reported in his newsletter. “Our priest got drunk and engaged in a totally debauched orgy in Wizard’s wood while Swenson’s freehold burned to the ground.” Gygax thought this sounded like a game in its own right; his daughter liked the name Dungeons & Dragons.

The game was a massive success, especially among fantasy readers. But there was, as Nachtwey puts it, an aspect of ludicrousness in the fantasy role-playing game that the fantasy novel, if it could not eliminate it, had tried to discourage. Tolkien, in his 1947 essay “On Fairy-stories,” had written that fantasy was the province of literature, where the natural glamour of the written word could make anything plausible. Dungeons & Dragons was more akin to the Gothic plays put on by the March sisters, whose magical proceedings are undercut by amateur stage effects, collapsing scenery, and unintended farce. Theater, Tolkien felt, had no business with fantasy; the audience was already too busy trying to accept the “magic” by which the players disappeared into the most mundane roles. “It is a world too much,” wrote Tolkien. But this is precisely what Dungeons & Dragons offered that the fantasy novel never could: the chance to enter an imaginary world with one’s disbelief miraculously intact — to be Quixote and Sancho at once.

It is notoriously difficult to explain Dungeons & Dragons to someone who has never seen it played. It is sometimes described as a “conversation,” but really it is a blend of bad writing, bad acting, and not a little paperwork. Players assume responsibility for characters with powerful abilities: an elf necromancer from a family of aristocrats, say, or a half-orc paladin atoning for past crimes. Players tell the referee, called the dungeon master, what they would like to do; the dungeon master directs them to roll some dice and add some modifiers, then narrates the outcome. Nearly anything can happen. I could tell you that, in my years as a dungeon master, I have watched players wrestle cultists atop a moving train and battle an elven goddess in an underground temple; I have also watched them ride around on giant owls, have freaky sex with spider-legged priests, and make a lot of strawberry jam. But conventional wisdom holds that talking about one’s campaign is about as interesting as talking about one’s dreams. Most D&D campaigns are private affairs that leave few traces outside of scribbled notes and fond memories. No description can capture the rush of the game or the general anarchy wrought by the whims of the dice and the spontaneity of the players. For this reason, it is difficult to develop a proper aesthetic account of D&D. It is less like reviewing a book and more like reviewing a book club.

We might begin with the idea of role-playing. The earliest players approached D&D like just another war game, blazing blithely from one dungeon to another. But as the game’s base grew — and its competitors multiplied — players began to debate the correct relationship between a role-player and his role. “One must get inside his character,” argued one game designer, “see what motivates him and makes him unlike any other, breathe life into him as an individual, and above all surrender one’s 20th-century self to the illusion and be that character.” This was easier said than done. The editor of a popular fanzine apparently required her players to speak exclusively in the third person, lest they smuggle in too much of themselves. But even players who make a conscientious attempt to adopt new personalities quickly discover that, to do so, they must keep their characters at arm’s length. That gap becomes dramatically clear in cases where players choose to act against their own interests, deliberately allowing their characters to be swindled, ambushed, or even killed. I once witnessed a player slit her own throat rather than be forced to betray a beloved friend.

These paradoxes twist around the game like briars around an enchanted tower; at the window stands the dungeon master. An effective DM will provide a steady flow of vibrant narration, clear direction, and improvised performance; she must also appear convincingly knowledgeable about the imaginary world, from its political intrigues and religious factions to what, if anything, is lurking behind the next door. But even as the dungeon master must personify the players’ desire to visit the imaginary world, she is also responsible for withholding it from them. Gygax felt that players should not even have a full picture of the game’s rules, writing that many of the game’s pleasures come from “not knowing exactly what is going on.” It is expected, for instance, that players will have to ask their dungeon master whether their characters recognize a glowing rune or can quote the ancient scriptures. Even an affirmative answer from the DM may reinforce this ignorance: The player knows that he knows something, rather than knowing it directly. The result is that D&D’s players tend to experience their own presence in the world as a cosmic absurdity that can never be fully explained. This was what the very silly 2023 film got right: Most D&D campaigns are about people attempting, like so many fish out of so much water, to do things they fundamentally do not know how to do. Even the game’s most enduring scene of accomplishment — the looting of dungeons — testifies to a kind of repressed understanding among players that, while this whole world may be for them, they nonetheless do not belong in it.

Few D&D players can shake the bittersweet sense that the imaginary world is always slipping away. A proper session takes at least four hours, which makes scheduling a headache. The game’s serial structure also means a single adventure may be stretched out over weeks or months. This is to say the primary experience of playing D&D is not playing D&D: One spends most of one’s time remembering, discussing, and missing the imaginary world, which vanishes at the end of each session like a dream with the dawn. This nostalgia for something that does not exist — and the peculiar sense of having made something up just to miss it — is intensely pleasurable for many players; it is a way to play at cheating death. D&D’s original system of magic reflected an awareness of this. “Once cast, a spell is totally forgotten,” wrote Gygax in the Players Handbook. “The mystical symbols impressed upon the brain carry power, and speaking the spell discharges this power, draining all memory of the spell used.”

Of course, one could always memorize the spell again the next day; the point is that characters, like the people playing them, have to choose to put their limited time and energy toward reenchanting the world. The imaginary world of a novel at least seems to enjoy an independent existence; one opens up the book and there it is. But the world of a role-playing game must be summoned over and over by the force of collective intention.

Tolkien, for his part, thought that fantasy affirmed the “endlessness of the World of Story”; but he also believed it should help console us in the face of our mortality. It is important to remember The Lord of the Rings, despite its fantastical creatures and mystical relics, is really about the disenchantment of Middle-earth. Hence the wistful beatitude of the Elves, whose departure for the Undying Lands across the sea suggests that one must leave behind the invented world in order to partake of eternal life. (Remember that for Tolkien, a devout Catholic, even the real world was invented.) Likewise, Tolkien thought fantasy should warn us of the perils of extending one’s story indefinitely — what he called “endless serial living.” The One Ring is a perpetual plot engine, a literal narrative loop; the wizard Gandalf says of it that one who is seduced by its promise of immortality neither lives nor dies but “merely continues.” “I wish I had never seen the Ring!” cries Frodo Baggins, who will soon be propelled into a wide world of haunted tombs, deadly monsters, and wicked men. But when the brave little hobbit finally reaches Mount Doom, he cannot bring himself to cast the accursed thing into the fire — as if he suddenly realizes ending the Ring will end the novel as well. This may have been the true meaning of evil for Tolkien: the desire to hold on to any world for too long.

In this sense, there really is something evil about Dungeons & Dragons. What I mean is that imagined worlds are precious; we who succumb to their power may find them very hard to give up. “It is no easy thing to dismiss from my imagination the images which have filled it so long,” wrote Brontë of her own invented world. “They were my friends & my intimate acquaintances & I could with little labor describe to you the faces, the voices, the actions, of those who people my thoughts by day & not seldom stole strangely into my dreams by night.” I do not mean D&D always inspires some sort of pathological relationship, as imagined by its early critics, though I often do find myself fiddling like Frodo with the magic world in my pocket. Tolkien associated “real” magic, as practiced by magicians in our own world, with a ruinous desire for power. I suspect this was because, as a man who had spent decades meticulously creating an imaginary world for his own private enjoyment, he knew that desire itself was already a kind of magic. As it happens, the Wish spell has always been the most powerful enchantment in all of D&D, where it allows a player to remake reality. DMs were advised to interpret wishes with utmost discretion, lest players ruin the game or break the world. But that world had never been consistent to begin with; it hung together through the persistence of a wish. Such a world may not have been real. But the wish always was.

Related