Yesterday, Tomorrow, and Banished Forever

After waiting over a decade to get in, the Andersons were kicked out of Disneyland’s most exclusive club. They would not go willingly.

September 3, 2017, was like so many other late-summer evenings at Disneyland. As the heat began to break on Main Street, swarms of exhausted families packed up their impulse purchases and their double-wide strollers and called it a day. It was almost 10 p.m. when security received an urgent dispatch. A guest was apparently showing signs of distress on a log-cabin-style bench outside Grizzly River Run. Officer Robert Rodriguez arrived on the scene dressed in his uniform with rainbow Mickeys on the short sleeves and a gold-trimmed peaked cap. Rodriguez asked for the man’s license; instead, he pulled out his card for Club 33, the park’s secretive, invitation-only private club.

Rodriguez did not realize yet that the barely cogent man was Scott Anderson, Club 33’s most notoriously outspoken member. But he knew he needed to get him out of the park — conspicuous drunkenness at Disneyland is strictly forbidden. He asked Anderson to call a friend to come collect him. “Come get me,” Anderson snarled into his home screen. Growing increasingly frustrated, Rodriguez took Anderson’s phone and returned a missed call from what turned out to be another Club 33 member, Adam Torel. Torel was nearby at the Grand Californian Hotel. He rushed back to find his friend surrounded by security guards. “Guest Adam showed up and said he would help Guest Scott,” Rodriguez would later write in his official report on the situation. Torel pushed Anderson slowly out of the park in a wheelchair, past stragglers leaving the World of Color light show and bachelorette parties staggering down the imitation cobblestone in their matching T-shirts and sashes.

Five days later, Anderson received a letter letting him know that his, along with his wife’s, Club 33 membership had been suspended. A member of Club 33 has to abide by certain rules, and Anderson had been allegedly drunk in public. Game over. It had taken him and his wife nearly a decade to get into the club in the first place, and since then, they’d spent about a third of every year in Disneyland. They celebrated nearly every holiday at the club, their son’s 21st birthday and others, a handful of marriage anniversaries. And so instead of going quietly, the Andersons decided to sue to get back in, claiming breach of contract and slander. Anderson wasn’t drunk, he said — he’d had a vestibular migraine. And furthermore, he was being targeted. The Club 33 he’d joined five years earlier, the very last thing that Walt Disney designed before he had died, had been ruined by expansion, greed, and punitive managers obsessed with waging campaigns against anyone who dared to complain about anything. “Instead of taking the feedback as an opportunity to improve the club,” Anderson says, “they took it as an opportunity to get rid of people.”

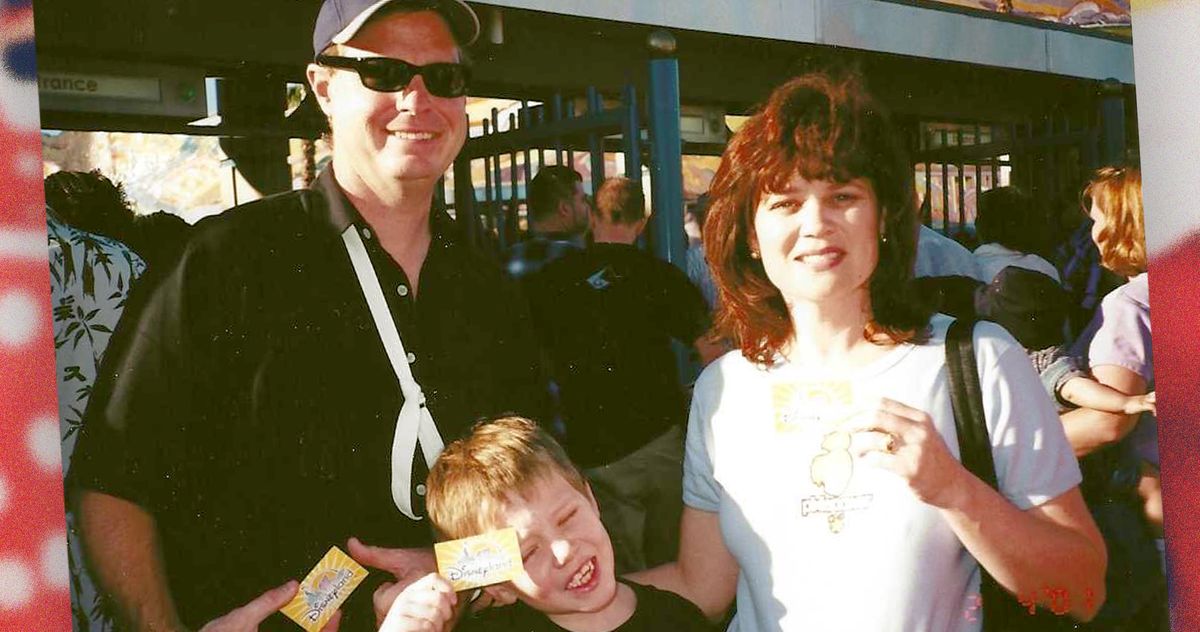

It wasn’t until Diana and Scott Anderson went to Disneyland with their child that they really understood it. The couple had been together since they were 16 years old, through college at Arizona State and afterward, when he took over his family’s electronics-manufacturing business in Mesa, a sprawling town outside Phoenix. Their earlier trips to the park were nice but not particularly memorable, Diana says — they went on a few rides, ate the churros, enjoyed the flag retreat. But with Stuart — “Stumanu” to his parents —the place transformed. Pushing him in his stroller down Main Street, under the blooming olive trees, the new parents felt calm. The air smelled of burnt sugar and popcorn butter, a train whistled in the distance, and their son was quiet. (Disneyland pipes scents onto its streets through so-called Smellitizers in the hopes of evoking this exact feeling.) As Stuart grew, they, like many millions of Americans, made Disneyland their special family tradition. “That’s how it gets you,” Diana says. “Stuart lost his first tooth at Disneyland. He went to the bathroom by himself for the first time at Disneyland. He fell asleep in the stroller for the first time in his life at Disneyland.” By the time Stuart was a toddler, the couple were traveling to Anaheim so often they figured it made sense to buy annual passes. For only $200 a year — it’s since multiplied —the family would be able to visit the park 365 days a year and get comped parking. Plus they’d receive a subscription to Disney News magazine. Best of all, they began receiving the occasional invitation to member-only events. In 2001, they were invited to a preview of California Adventure, a new park-within-the-park — 72 sprawling acres of Pixar-and-Marvel-themed rides and characters. Scott broke his shoulder earlier that day, but the family decided to make the trip anyway. “We weren’t missing the grand opening,” he says. By the time Stuart was 12, he’d been to Disneyland 115 times. He had experienced the 199-foot vertical drop on the Tower of Terror, ridden on California Screamin’, a roller coaster that soared over a giant lit-up Mickey head, and celebrated the park’s 50th anniversary, the so-called Happiest Homecoming on Earth.

The passes were nice. But as the years went by, they began to wonder about Club 33. Everyone who spends enough time at Disneyland does; it’s the ultimate bucket-list item for anyone who cares deeply about Disneyland. Diana had heard from friends that the wait list could take decades; getting in seemed as likely as finding a golden ticket. Still, she figured — why not just try? In the fall of 2002, Diana called member services and asked to be put on the list. Then, she says, “we waited.”

Walt Disney decided to build his own private club after visiting the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. The idea was to create his version of the suites he saw there, where Disney investors could entertain clients and bring their families. Like everything else at the park, it was designed with his obsessive attention to detail, with help from Mary Poppins’s set decorator Emile Kuri. Disney imported a reproduction of a Victorian-era French elevator to carry guests between floors. An animatronic vulture perched in the dining room was designed to chat with guests while they ate. (Microphones were hidden in lamp fixtures; an actor was hired to sit in a sound room, listen in, and chatter back.) The walls were hung with hand-painted animation sheets from the original Fantasia; a drawing room held Lillian Disney’s exotic butterfly collection. The dining room overlooked New Orleans Square, a replica of 19th-century New Orleans, so guests could look out over the throngs of visitors below while they ate. And the entire place was hidden behind a door painted in “Go-Away Green” — a proprietary-to-Disney color that is supposed to make it more difficult to spot.

Members would receive other perks too: They would have unlimited access to the park and free parking, speed through lines, and could rent out the club for events. “Club 33 is Disneyland’s new ‘center for VIP guest relations,’” read the original pamphlet. “With its opening, many of Disneyland’s traditional red carpet services for Very Important People — including guests of the United States Department of State and the clients and key executives of companies represented in Disneyland — will revolve around this distinguished address: 33 Royal Street, New Orleans Square.”

The club was six months from opening when, in 1967, Walt Disney died of lung cancer. But in the decades after it opened, the club, and its perks, has stayed mostly the same, the ultimate distillation of Disney’s motto, “Yesterday, Tomorrow, and Fantasy.” Little has been renovated, or moved, or changed. The membership stayed small, and the interminable wait list quickly became mythological, as much Disney lore as the secret elevator in the Haunted Mansion. At one point, “a spot wouldn’t open up for 18 to 20 years,” a current member says. Others estimate five or ten. An online inquiry submission form only says someone “may” be in touch if “an opportunity presents itself.”

Once in, members are given a list of governing rules. While drinking is permitted, members are never to become visibly intoxicated. Members are strictly prohibited from reselling official Club 33 merchandise, though many choose to ignore this. (Club 33 sweatshirts, mugs, and Minnie ears go for hundreds, sometimes thousands, of dollars on eBay.) Members are never to solicit celebrity autographs. (Tom Hanks is a member; so is John Stamos. It’s been rumored that Katy Perry and Taylor Swift’s feud started in the dining room.) Though photography is technically allowed, any social-media post considered to be “in poor taste” by management can result in a formal warning. In fact, failure to comply with any of these rules can result in a formal warning. And management has free rein to cancel any membership, for any reason, at any time. Then, of course, there’s the tacit understanding among members that they shouldn’t talk much about what goes on at Club 33. The intrigue is part of the appeal. Members wear 33 pins on their shirts or 33 studs in their ears as signifiers; others choose an Instagram handle that ends in the number. Articles written about the place rarely quote actual members. “It’s like Fight Club,” one told me. The sense of mystery has led to speculation. On forums, some Disneygoers wonder if the club is a cabal. (Disney declined to participate in the reporting of this story.)

By June 2012, Diana had given up hope on ever getting in. Stuart, already a young adult, had lost interest in anything related to the park. But then, out of nowhere, there it was: a small envelope sealed with a gothic “Club 33.” Her hands shook on the drive home from her P.O. box. She knew enough to know what this meant. Disney with no hassle, forever. Proximity to celebrities. Status. She couldn’t wait to tell Scott. “I said, ‘We got the invitation.’ And he’s like, ‘No way.’” The initiation fee was $40,000, plus another $12,000 annually. “I didn’t want to tell Scott the price because it wasn’t what he was expecting,” she says. But she hurried through the application anyway, afraid all the spots would be taken before she was able to finish. “Diana’s long-term intent was that when we get old, Stuart likes it,” Scott says. “We hoped the membership would live on forever.”

That fall, the Andersons attended their first members-only events: a tour of a new attraction, Cars Land, and Oktoberfest at Downtown Disney. There were Irish step dancers, lobster rolls, and limited-edition merch. Over beers, they chatted happily with other members about Disneyland news — rumors of plans to drain the Rivers of America and the return of the long-closed “Fantasmic!” show. Afterward, they stayed the night in a sprawling room at a hotel in the park. Scott was impressed. “It’s a different world,” he says. “I was like, Now I get it. Now I’m grasping why people would want to be a member.” Still, he was a little miffed when he learned from a new friend that he hadn’t received the same discount others had on their hotel room. Once they got back home, Scott called membership services. A manager named Diana Evans looked into the situation, apologized, and offered them a refund to reflect the discounted rate.

A guest felt heard in a place like this. Seen. The Andersons loved the little touches: how the bread and butter was always warm when it arrived at the table in the main dining room, how the floral arrangements always matched the season, that managers made a point to greet them by name. Minor celebrities, like The Office star Kate Flannery, joined them for drinks. “Even if I was alone, I never was alone,” Diana says. “Every time we would come over, everyone that we knew would come out of the woodwork and come sit with us.” By that summer, they were going to Disneyland nearly every weekend. They’d have lunch at the club, then take a ride on the Toy Story Midway Mania or bring friends for a VIP tour of the Haunted Mansion.

Not long after they joined, the club closed for renovations. This concerned the Andersons. Would the new, expanded dining room be as intimate as the original? As true to Walt’s vision? If Disney were alive, would he have demolished the Trophy Room to update the kitchen? They bided their time at the 1901 Lounge, a less-exclusive sister club on the opposite side of the park. Still, when Club 33 opened back up less than a year later, they were impressed. The doors were repainted a lacquered robin’s-egg blue. Cherished antiques like a club-footed console featured in Mary Poppins remained, thankfully, prominently on display. They especially liked the new Le Salon Nouveau, a drop-in lounge created to complement the formal dining room. But soon they found other problems. In late 2012, Scott learned, while talking to a fellow member, that platinum membership to the club — the level below his executive membership — came with essentially the same perks. He called management and convinced the club to cut him a check for $15,000. Later, they toggled back to executive for free. All of this, the Andersons would later learn from court documents, worried Evans, the manager who had helped Scott with the hotel discount soon after first joined. “If we permit the Andersons to transition back too easily, they (Scott) will boast like a peacock,” she warned her colleagues on December 31, 2014. “They both chatter to other members so much.”

In the summer of 2014, the Andersons went out for dinner with their friends at the club, Ted Crowley and his wife, Jennifer. Both couples had been members for about three years, and both lived in the Phoenix area. Ted worked in the same office as the Andersons’ financial broker. But one night, during a late dinner, Diana says, things took a turn and Crowley touched her inappropriately. After that, Scott made it his mission to get Ted kicked out of the club. In the meantime, he and Diana refused to visit if they knew the Crowleys would be around. On June 2, 2015, Scott emailed the club’s manager, James Willoughby, a subtle reminder: “Love the direction the club is heading,” he wrote. “Only negative here is [with] a few non-compliant members. Usual suspects I’m afraid.” Later, he RSVP’d to a wine dinner only after learning that Crowley would not be attending, “as he was the only reason that I did not put in in the first place.” Scott wrote again to Willoughby to say he overheard an employee, just back from maternity leave, complain that Crowley said he “loved hugging you and it’s not because of your big breasts.” Three days later, he followed up once more: “I am sure that Disney does not take sexual harassment lightly, so trying to understand the process here,” he wrote, signing the letter “Left Wondering.” (Ted Crowley didn’t respond to request for comment.)

For the next year, the couples managed to avoid each other, with other members running interference to ensure the Andersons and the Crowleys were never in the club at the same time. “It was odd if they were both in the lounge,” a current member says. “It was the Hatfield versus the McCoys.” But the Crowleys remained members, and in July 2016, Willoughby left his job as lead manager of the club. In an email to his replacement, Luke Stedman, he warned of the ongoing Anderson situation: Diana and Scott “seem to have nervous dispositions and are perhaps delusional thinking we spend time in our day trying to find ways to pinpoint member issues.” When he heard that Stedman would soon be starting, Scott sent an email of his own, introducing himself. “Hello Luke,” he wrote. “I am sure moving over to Club 33, that you are going to be very busy. My wife and I are going to be in the parks today through Wednesday. If you have any opportunity at all we would love to introduce ourselves and meet you in person. Please let me know if this is a possibility. Thank you and congratulations on the move.”

The meeting didn’t go as Scott hoped. “It was like one in the afternoon,” Scott says. “We were having a glass of wine. And he comes in, he sits down, and his approach was like, ‘So what’s the problem, what’s this about?’ We’re looking at each other just like, What the fuck? We’re just here to say, ‘Hi, this is who we are.’” The relationship devolved from there. A few months later, Scott wrote to Stedman that Ted “continues to flaunt [sic] the rules … and somehow continues to maintain his membership when others have been banished for less.” As a onetime assistant to disgraced former U.S. House Speaker Dennis Hastert, Stedman had some experience handling conflict. He asked his staff, “Anyone have some backstory?” Evans responded promptly. The two arranged a call.

If the club maintained its essence after the renovation, Stedman ushered in changes. According to Club 33 administrator Bonnye Lear, who died in 2024 after being thrown from a golf cart racing through Critter Country, the warning policy had been vague under former managers. One current member told me that drinking, which had always been tolerated, if not encouraged, came under enhanced scrutiny when Stedman took over. “We’re normal people. We don’t drink a lot,” this member told me. “I have one or two cocktails,” but with Stedman in charge, “I’d be like, Am I going to get in trouble for something?” The Andersons, meanwhile, were convinced Stedman hated them. They began to believe that the managers viewed members as mere visitors; that they were wielding their power recklessly over those they perceived as enemies of the club.

Another manager, Allicia Reynoso, also seemed newly frosty under Stedman’s rule. Scott became paranoid that she was resentful of Diana: “She hated the fact that my wife, who was there 80 times in a year, is able to have this life of luxury and hang out.” Within months, Stedman started closing the club earlier. “The biggest benefit we ever had was the fact that we could stay in the lounge until the park closed and walk out of this empty park,” Scott says. He tried talking to Stedman about this; the conversation grew heated. “That’s a huge fucking benefit,” Scott remembers saying to him over the phone. “And Luke says, ‘Hours aren’t benefits!’”

Soon after, Diana was written up for using inappropriate language during lunch. “Mrs. Anderson asked if ‘that little shit’ Mike” — the bartender — “was cutting her off,” server Alastair Baird wrote of the incident, during which Diana also reportedly spilled a drink. He added, “She asked me to sneak her a bottle so she could pour for herself under the table, and I reminded her that she tried that last year at an event and that Allicia was aware of that.” In Diana’s version, any colorful language was said in jest. Still, the club issued her a warning and a 30-day suspension. In a lengthy email to management, Diana vowed to take “Herculean action” to remedy the situation. “She has the right attitude,” Stedman wrote to his team. “We also now have a warning on record.”

But the managers only grew more irritated with the Andersons. In late March 2017, Diana organized a Saturday “kiosk krawl,” with stops at restaurants across the park. Two days before the event, Diana emailed 1901 manager José Barragån to remind him that “the Kiosk Gang is planning to meet up at 1901 at 1 p.m.” Barragån forwarded the message to another manager, James Towning, who put the hospitality teams at both clubs on high alert. “This is not an excuse to overserve or allow poor behavior,” he warned. “This ought to be fun,” another manager wrote with obvious sarcasm.

Within days, a member named Steve Cifelli had complained to Evans about “offensive social media posts” from the event, which she shared with the management team in an email titled “Weekend Activities.” Stedman, who copied in top Club 33 brass, asked to see the posts. Though Cifelli would later testify that he hadn’t snitched, the very next day, he emailed himself a series of screenshots from the Club’s members-only Facebook group. The images showed two female guests drinking spilled red wine off the Disneyland sidewalk with straws, a guest pretending to hitch a ride on a motorized wheelchair with the caption “too drunk to Uber,” Scott drinking a Corona Light with the caption “Good night Kiosk Krawl,” a male guest “asleep” in a stroller while a small girl in face-paint stands to the side with the caption “She wasn’t using it, so why not?”

On the Sunday before Labor Day 2017, the Andersons had been avoiding Club 33 on purpose. They felt like the waiters were watching them. So instead, they spent the day at 1901. (Club 33 members are automatically given 1901 membership.) During a Fantasy Football draft with friends, they ordered two bottles of Sangiovese, several beers, beef tacos, and two pulled pork sandwiches. At 9:31 p.m., the tab was reopened to accommodate one more bottle of medium-bodied red. Then, all of a sudden, Scott says, he didn’t feel well. He recognized the symptoms immediately. A vestibular migraine coming on — and fast. The first one had taken hold 30 years earlier, on the drive to his old Pinetop-Lakeside cabin. The condition was triggered by a lot of things: altitude, junk food, rides that send you in loops, barometric-pressure changes, the taurine in Red Bull, and red wine. “I started popping my ears and belching. It’s just what occurs before I get going into migraine mode. I was like, ‘I got to get out of here,’ told Diana my head was bothering me, and I was going to go back to the hotel. I excused myself and I left.”

He’d barely left the club when he realized he could go no further. “My head started exploding and I sat down on a bench and I’m like, Fuck. Now I’m screwed. Then I was just waiting. Diana was going to tab out, but the way Diana tabs out is she’s shooting the shit with somebody. She’s there until close and forced out. I was like, Shit, is she coming? She can help me get in the fucking car and go back to the hotel. Then the security guards come up and found me sitting on the bench.”

After Officer Rodriguez dialed Torel, the Club 33 member, he placed one more call — to Reynoso. “He calls her cell-phone number, says, ‘Hey, I’ve got a Club 33 member here, and it’s Scott Anderson.’ It’s like the world just lit up for Allicia,” Scott says. An hour later, Reynoso requested the security report. At 1:22 a.m., she forwarded it to Stedman, who responded, “What we need to secure is a statement from the security manager. Really needs detail in the statement,” he wrote back. “Can you get that for me?”

Back in Arizona, they received a letter in the mail telling them they were officially banned from the club — signed by Luke Stedman. “Please mail your Club 33 Membership Cards to us at your earliest convenience,” it read. “We knew we were being targeted,” Diana says. “It was extremely obvious we were being targeted.” On December 4, 2017, the Andersons filed in Orange County Superior Court for breach of contract, defamation, and a full reinstatement of their Club 33 privileges.

The case dragged on for over seven years — through six judge reassignments, a pandemic, and a successful summary-judgment appeal by the Andersons, who argued that Disney was being permitted “to terminate a membership for any reason at all — good, bad, or indifferent,” which allowed the case to go to trial. Finally, on August 5, 2024, the Andersons were able to present their case before a judge. And from the outset, it didn’t go their way. The judge rejected Scott’s idea to have jurors simulate the walk from 1901 to the Grand Californian to prove it couldn’t be done drunk. It took a jury only 45 minutes to reject the claim that the Andersons had been improperly ousted. “Orange County is fucking Disney’s neighborhood,” Scott says — everyone has a connection to Disneyland. They appealed the ruling in December.

Since being exiled from Club 33, many of the members with whom the Andersons were close no longer answer their calls. Instead, they’re spending more time at another Los Angeles members-only club, the Magic Castle. That club — meant for magic enthusiasts — is bigger than Club 33. It has five bars, a library, and a couple thousand members. It’s not that hard to get in. A performer at a 9-year-old’s birthday I recently attended offered me free guest passes in exchange for a five-star Yelp review. Still, there are some touches that a Club 33 member might appreciate — in the music room, a piano is played by an invisible “Irma,” the Castle’s resident “ghost,” who takes musical requests. There are Houdini seances. There are cocktails.

On a recent Friday, Diana and I met there for an early lunch. When I arrived, the director of club experiences, Ben Roman, was handing her magnets with updated staff phone numbers. “She knows everyone,” says her friend, who works as a tour guide for another big entertainment conglomerate. Diana took a couple extra magnets to put in her purse. The place looks a little tired, and there are no rides, but that’s okay. She showed me how to tell when you’ve stepped outside the original “house” of the Magic Castle. It’s a detail about the size of the wooden planks, something only a true members’ member like her could appreciate. She joked with the waiter about the bartender Chris or, as she likes to call him, “Stunt Janeen,” because he’s nowhere as fast as the club’s director of food and beverage, Janeen Puente. The waiter nodded and laughed graciously. Diana ordered another glass of white wine, which she drank slowly with ice cubes. Toward the end of lunch, Diana asked the real Janeen to give me her assessment of the Andersons as members. With a little needling she admitted, “They are lovely members.” Diana asked, “Were we ever obnoxious, drunk, loud, abusive?” No, responded Janeen. “The staff love them.”

Additional reporting by Lydia Horne