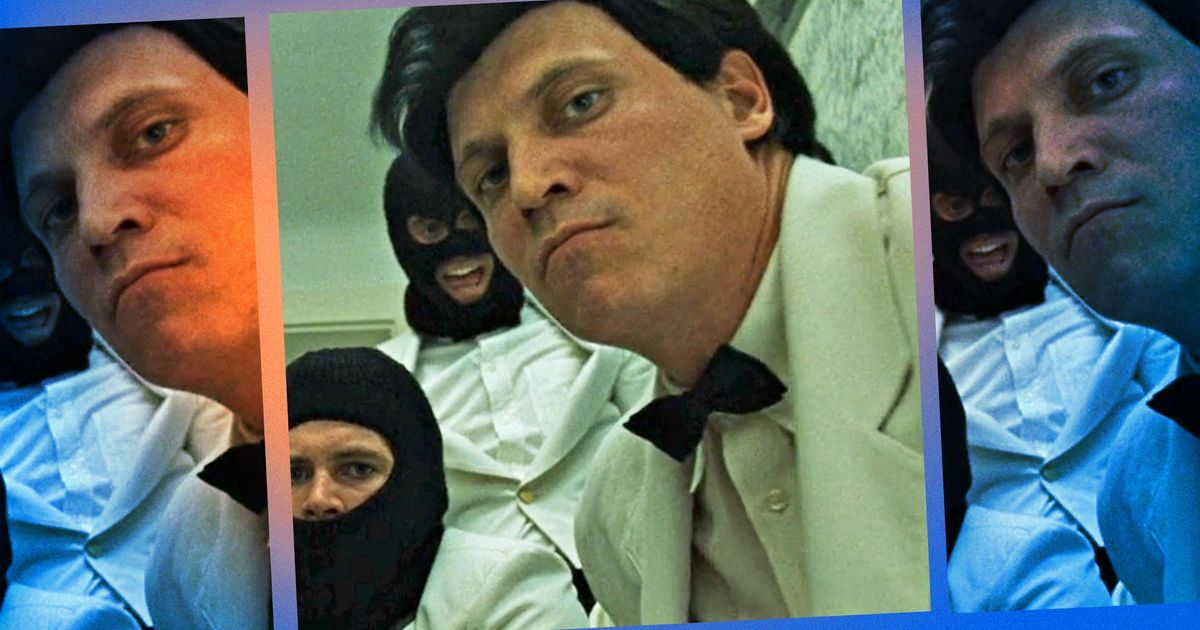

Holt McCallany Answers Every Question We Have About Fight Club

On working with the man he calls “Meat” (last name Loaf), the catharsis of terrorizing a priest, and his decades-old beef with Rosie O’Donnell.

Holt McCallany can talk for a long time about filmmaker David Fincher, with whom he’s worked three times. On the beloved crime-thriller series Mindhunter, which was unexpectedly canceled by Netflix after its second season. On Alien 3, the prison-planet sequel that was Fincher’s directorial debut and so plagued with interference from 20th Century Fox that Fincher wouldn’t talk about the movie for years. And on Fight Club, the cult classic that has been misinterpreted in bad faith since it came out 25 years ago. McCallany can mimic Fincher’s tone and jokingly recites his advice from years on set together. And he can just as vividly recall a grudge he’s harbored since the movie’s release.

“I remember sitting in a dentist’s office, and the TV happened to be The Rosie O’Donnell Show. She’s talking about Fight Club and she says, ‘Whatever you do, don’t see Fight Club. It’s demented, it’s depraved. I don’t think I’ve ever hated a movie more.’ I’m thinking, Gee, Rosie. Do we go on TV and bad-mouth your show? Is this really necessary, this kind of abuse?” McCallany says. “It angered me. I won’t pretend otherwise, because we were very proud of the film, we had worked very hard on the film, and we were very loyal to David.”

In Fincher’s adaptation of Chuck Palahniuk’s novel, McCallany plays the Mechanic, a devoted follower of anarchist philosopher Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) whose unflinching glare and menacing physicality are always in service of Durden’s anti-consumerist ideas. McCallany exudes such certainty of self that once you notice the Mechanic cheering in the background of fight scenes, doing chores in the Narrator (Edward Norton) and Durden’s dilapidated mansion, or threatening to “take” a police commissioner’s testicles with a knife, you’ll keep looking for him, wondering what those wild eyes and set jaw are getting up to. The Mechanic tightened McCallany’s relationship with Fincher (who had previously wanted him for a small role in Se7en), and his melancholy-yet-adamant delivery of the film’s iconic mantra — “His name was Robert Paulson” — indicated how fully he could inhabit heavies with a heart.

When I say Fight Club, what’s the first thing you think about?

Very rarely in an actor’s career is it clear and apparent, while you’re shooting something, that you’re a part of something really memorable. You’re making a classic, and you know it. I’m talking about once or twice in a career. I did feel that way also on Mindhunter, when I got into some of those long interrogation sequences with some of the serial killers, who were brilliantly cast and were all excellent actors. I knew this was not your average cop show. And with Fight Club, Jared Leto used to walk around and go, “We are the Fight Club elite.” To give Jared his due, I remember when we were shooting, he was trying to think of a name for his band, and he would say, “What do you think of 30 Seconds to Mars?” We’d go, “Hmm. 30 Seconds to Mars. That could work,” but we were all a little skeptical. And let me say, he did it. I’ve listened to some of the music. Some of it is really good. He’s got a lot of fans. He had a very clear vision of what he wanted to do as a musician, and he did that at the same time as continuing to grow as an actor and eventually becoming an Academy Award winner. So a little hat tip to Jared Leto. Sorry we doubted you, bro.

Where were you in your career when Fight Club happened? Were there specific kinds of roles that you were looking for, or avoiding, at that time?

When I was growing up, one of my very, very favorite writers was the late Norman Mailer, who used to say, “You can only present yourself to the American public as one of two things. You will either be some kind of a warrior or some kind of a lover. Every character that you ever play will be, at its essence, some variation on one of these two themes.” I had been, clearly, someone who played the warriors in our society, and I was comfortable with that. That’s certainly the kind of character that I played in Fight Club. But if you ask me what kind of a character did I really want to play, it would be a warrior who’s motivated by his love for something. That could be the love of a woman, but it could also be the love of a particular idea. It could be the love of a particular cause. It could be the love of country. It could be a desire to get to a particular place for a particular reason. It could be that kind of longing. He’s a warrior and he has to overcome obstacles in order to achieve it, but it comes from this place of love. In the case of Fight Club, it was a warrior who is in love with this idea that Tyler Durden is presenting to us, and with this cause, and with this movement, and with its inherent logic and validity. I’m willing to go out and fight for it in any way that I’m asked to.

You worked with David Fincher previously on Alien 3. Did you audition for Fight Club, or did David offer it to you?

I don’t remember reading. I do remember a meeting that took place in David’s office — or it might have been in the office of Laray Mayfield, his extraordinarily gifted casting director, who has been with David for many, many years — and him offering me the part. I had read and loved the book, and I had worked for David. He wanted me for a role in Se7en that I was unable to play, the part that John C. McGinley eventually played, a helicopter pilot at the end. The way David shoots that, you can’t even really make out who it is. But I wanted to be in Se7en. I had tremendous loyalty to David. On Alien 3, I had some hesitation about signing on, because in the original script, it’s only one scene and the character rapes Sigourney Weaver. I was living with a girlfriend at the time who said, “You’re going to go to London for five months and shave your head bald to play one scene where you rape somebody? I don’t think so.” And I was like, “Yeah, maybe you’re right. I really like the director and it’s part of this big franchise.” And she goes, “I don’t want you gone for that long. And just one scene as a rapist? You play bad guys all the time.”

I called the casting director, Billy Hopkins, and I said “Billy, it’s hard for me, but I think I’m going to decline.” And he said, “David Fincher is going to want to speak to you. Can he call you at home tonight?” David called me and he’s like, “What do you mean you don’t want to do the movie, dude?” And I was like, “Well, no, David, it’s not that. It’s just that he’s only got one scene, and it’s a rape scene.” He goes, “Dude, dude. You’re going to be in lots of scenes. I’ve got lots of ideas for your character. Yes, I do need the rape scene, but that is by no means your only scene in the movie. You’re going to be all over the movie. Trust me, I want your character to participate in a lot of different ways.” And I said, “Okay. Then I’m in.” And true to his word, he did exactly that. In David’s version, he really did allow the convicts to express themselves. And then the studio took the film away from him in the editing process, and any scene that didn’t feature Sigourney Weaver suddenly hit the floor. And nothing against Sigourney. I’m a fan. She was a big, big star, and I was Schedule F, the lowest amount of money that you can pay an actor according to SAG. There’s a tremendous disparity, and then I have to rape her, which I was nervous about, you know? But she was very gracious. She came to me before and said, “Holt, whatever you think you would do, whether it’s grab me or slap me, I want you to know that that’s okay. I want this to feel real.” That helped to allay some of the fears I had about going too far — going too far with anyone, but especially with the star of the movie, who’s the highest-paid actress in Hollywood. You don’t want to overstep. But she’s a consummate actress. She’s a very generous person and considerate of her fellow performers, and probably could sense that I was nervous about it. And I was very grateful to her.

So David says he wants you to be in Fight Club. The characters don’t really have backstories in this. Did you imagine more about the Mechanic than what we see?

Sure. In a story like this, you have to create a character history. The Mechanic is a more prominent character in the book than he is in the film. But nevertheless, it’s still important to make those kinds of determinations, even if they’re only for yourself, even if they’re never going to be articulated in the film. As long as you know it and you commit to it, it’ll play. The audience will subconsciously pick up on that. I used to type those things up. I used to print them out. I don’t have it in front of me. But I decided that he was divorced and lived alone and drank too much and was tremendously dissatisfied with his life on multiple levels.

What was the atmosphere like on set?

There was a certain ambience. There was a certain camaraderie. There’s forty guys in the film — space monkeys. We’re there all the time and we really bonded. There were actors that I developed close friendships with, like my friend Meat Loaf. Or my friend Eion Bailey, who has a prominent role in the film; he was just a young guy at that time. We were all young. But we knew that we were a part of something that none of the other studios was making. I didn’t predict how controversial the film would be upon its release. I remember sitting in a dentist’s office, and the TV happened to be The Rosie O’Donnell Show. She’s talking about Fight Club and she says, “Whatever you do, don’t see Fight Club. It’s demented, it’s depraved. I don’t think I’ve ever hated a movie more.” I’m thinking, Gee, Rosie. Do we go on TV and bad-mouth your show? Is this really necessary, this kind of abuse? It angered me. I won’t pretend otherwise, because we were very proud of the film, we had worked very hard on the film, and we were very loyal to David.

It was very easy for me to connect with the idea that I’m going to get in a fight with a priest, because I’d been fighting with priests throughout the entirety of my youth.

Brad and Edward are very good in the movie, as is Helena Bonham Carter. I thought it was Meat Loaf’s best work, and he wasn’t always valued by the music industry in the way he deserved to be valued, having made the third-biggest-selling rock-and-roll album of all time. He was often treated like a joke by certain people in the music industry, and we actors did not treat him that way, and I think he appreciated that very much. Right up until his death, I would get occasional phone calls from Meat. We called him Meat, because “Meat Loaf” is not one word. His first name is Meat, and his last name is Loaf. He’s Meat Loaf. Anyway, I didn’t appreciate Rosie’s remarks and I didn’t agree with them, and I didn’t understand why she felt that she had to be so pejorative of our work. A lot of people really didn’t like the film. But you can’t control how audiences are going to respond to a piece of material. And frankly, over the course of time, the truth will out, and the film has become an iconic film and a cult masterpiece. I still get 15-year-old boys stopping me in airports, saying “‘His name is Robert Paulson.’ You’re that dude. Say it one time, man. ‘His name is Robert Paulson.’” It had a profound impact on a lot of people.

You have a scene where, after Tyler challenges all Fight Club members to start a fight with a stranger, you start a fight with a priest. You’re soaking the priest and his Bible with a hose and chasing him down the street. It’s probably the funniest scene in the film. What do you remember about it?

I was educated by priests my entire boyhood. I started with the Christian brothers in Ireland when I was only 5 years old. Later, my parents divorced and I was sent to live with my maternal grandparents in Nebraska, where I was a student at Creighton Prep, which was an all-male Jesuit school. I got expelled from that school. I got sent to Newbridge College, which was Dominican priests in Kildare, which is kind of halfway between Dublin and Cork, in the middle of nowhere. I was regularly beaten, because I was a wise ass, and because you can’t get away with that in Ireland. Certainly not in the ’70s. They’d just [mimes backhand], you know what I mean?

I had run away to California with dreams of becoming a film actor, and my parents tracked me down and they sent me to Newbridge College, where my father had been a student 40 years earlier. I had long hair, and they cut all my hair off and they put me in the college blazer and the college tie. My first day at school, I was standing in what they call the refectory, or what we would call the cafeteria. You’re never allowed to talk, except at lunchtime. I’m standing in line and they slopped some food on my tray. It was just absolutely disgusting. There was a priest standing next to me, Father Conway, big, tall guy, Dublin guy. And I said, “I know this isn’t what you guys eat in the rectory.” True enough, the priests do have a different kitchen in their residence, and it’s a different menu, and it’s far superior to what we had. But you’re not supposed to make reference to that, and this is day one! He cracked me with an open hand, hard, and I flew ass over teakettle, crashing down, and my food was all over the floor. I was trying to decide, Am I going to go for it? I was a precocious kid, and I was tall. And I see 400 boys going [putting their hands up in a “stop” motion], and he looked at me and he said, “Now you’ll clean that up, and you’ll go to your cubicle, and you’ll learn to keep a civil tongue in your head.” I never forgot that. “You’ll learn to keep a civil tongue in your head.” That was day one. And it was all downhill from there. So, you know, beating up a priest …

I’ll tell you a story. Twenty years later, I get a job playing an Irish gangster from Cork on an American television show called Heroes. The Cork accent is [slips into accent] way up there. It almost has kind of a Caribbean lilt to it. Even some other people in Ireland can’t understand a real thick working-class Cork accent. I flew to Cork, and Jack Wolfe, an actor friend of mine who was from Cork, was showing me around. I would go to these rough pubs along the waterfront, and I had a tape recorder and a little microphone and my script, and I would walk up to guys and say, “Do you mind saying a few of these lines into this microphone?” My friend was absolutely convinced that we were gonna get our teeth knocked out. I got all this stuff: the real Cork accent, all my lines. We’re driving back from Cork to Dublin, and I see a sign that says Newbridge. And I was like, “Oh my God, that’s where my school is, Newbridge College. Pull the car over. We’re going to go look for Father Conway.”

My intention was not to beat the shit out of Conway, because he would have been a very old man at that time. My intention was just to give him a little bit of a scare. I’d say, “Hey, Father. My name is Holt. Do you remember what you did to me? Look at me closely. Tell me you remember.” Just so he has that one moment in his life where he’s not quite sure what’s going to happen next. Just so I see that fear in his eyes, and then I’ll leave it there. I’m walking around the halls, and everything seems small, because now I’m a full-grown man. At the time, it was like this ominous prison for boys, and now it just seems like this quaint little place on the banks of the River Liffey. I see a priest. I say, “Excuse me, Father. I’m an old friend of Father Conway’s. I’d love to have a chat with him.” He says, “Father Conway died a couple of years ago. He died young. We miss him very much.” I said, “Oh, I see. Well, my condolences.” I never got my revenge. But on Fight Club, it was very easy for me to connect with the idea that I’m going to get in a fight with a priest, because I’d been fighting with priests throughout the entirety of my youth, and I was always on the losing end of it. And we were actually instructed by Tyler to lose the fight, but it seemed to me that I could still get a couple of licks in before I lose.

So, “cathartic” is the way to describe that.

Yeah, that’s the word I’m looking for.

You’ve mentioned what I think is the most enduring moment of the movie, the “His name was Robert Paulson” scene. The Mechanic says, “I understand. In death, a member of Project Mayhem has a name.” Most of the male members of the cast are in this scene. People still quote it to you. What do you remember about filming it?

Every actor wants to be in a great film that will stand the test of time, and if you’re lucky enough to be in that position, then what you hope for is that you’ll have a really memorable moment. I was fortunate enough to have both. I’m in Fight Club, and I have that scene people still remember after all of these years. I really liked Meat, and we had spent a lot of time together. Because the personal relationship exists, there’s a more personal kind of feeling attached to playing the sense of loss. Not that you can’t create that as an actor, but when you don’t have to because you already feel that way, it’s even easier. It’s a powerful scene, it’s a scene that involves all the actors. And it was meaningful to me because I realized while shooting it that this was a scene that was really gonna speak to audiences and really be memorable and really be my moment to shine just for an instant.

Right up until his death, I would get occasional phone calls from Meat. We called him Meat, because ‘Meat Loaf is not one word. His first name is Meat, and his last name is Loaf.

The film is primarily a two-hander with a girl: It’s Brad, it’s Edward, and then Helena’s very important contribution. And then Meat Loaf and Jared Leto and myself and Eion Bailey, we’re there, but we’re more peripheral characters. But not at that moment. At that moment, the Mechanic is a very important character in the story. David staged the scene in a way that you see the Mechanic understands, or believes he understands, what’s going on, and it’s a chance for us to show the collective madness of the group. It was a very proud moment for me as an actor. I remember going to the wrap party and the editor coming up to me and saying, “You’re great in this film, man. You don’t have a lot, but what you have is really good.” I was very grateful for those words, and I was very grateful to David for giving me the opportunity and for remembering me after all those years had passed since Alien 3. And then, of course, he remembered me again, and he brought me back for Mindhunter. As a consequence of that, I’ve been associated with being one of his preferred guys, and I don’t think there’s any higher compliment that an actor can have in this town.

When I was rewatching the actual fight scenes, I kept looking for where you were in the crowd, and you’re always reacting in some way. How much freedom did you have during the fight scenes to come up with what the Mechanic would be doing?

You do in rehearsal what you think is right. You make certain choices. And if David is seeing something in the frame that’s distracting him or he thinks might be pulling focus away, oh, he’ll tell you. But until I get the note, I’m gonna assume that he’s comfortable with what I’m doing. You gotta stay active and you gotta stay busy when you’re in frame. Even my character in Mindhunter — he’s a chain smoker, he eats a lot of bad food, he drinks a little more than he should. You find business. There was a scene in Alien 3 where we’re all preparing for Ripley’s arrival, and David was shouting at me, “Find stuff to do, Holt.” You can’t just be sitting there in frame scratching your head. Find some business.

When you look back on Fight Club and your second time working with David, what did you learn about yourself as an actor?

That I believed that I had everything it took to compete on the top level of American actors. I had tremendous admiration for both Brad and Edward. They were both movie stars. They’re both very talented. Having spent that much time in their proximity, I thought, These guys are among the very best that we have, and if I can hold my own here, then I belong. Then I was right. When I was 14 years old and I took a Greyhound bus to Los Angeles because I wanted to be a film actor, there were no guarantees that it was ever going to work out. But now there are. I’m on set with the best director of his generation and with two of the finest actors of their generation, and I feel right at home. I feel like I’ve got everything it takes to continue on and to work with men of this caliber for the next 40 years. That’s what I took away from it: that my instincts were right, and that I could be a successful actor in Hollywood. It’s always hard to feel like a success in this town.

The last thing I want to ask you is in the car-crash scene, when the Mechanic is asked what he wishes he had done before he dies, his answer is build a house. I’m curious what your answer would be to that.

My own father was kind of a gypsy. He was a producer. He lived in London for a time, he lived in Chicago, he lived in his native country of Dublin, he lived in Cape Town, South Africa. He was always jumping around, but he never really had a fixed residence. So “build a house” had more personal significance to me, because what it was really saying was, to have that place that is my principal and permanent residence, to which I always intend to return. This is my place that I built, that I own. That’s something that my father never thought was important, but it was important to me. Ricky wants to paint a self-portrait — I don’t need a self-portrait. I want a house that will always be there, no matter which way the wind blows, no matter what the weather is, no matter what life’s ups and downs have in store for me. I have a refuge. An actor isn’t always elated with the scripted dialogue. On this occasion, I was very happy that that was my line.