Is Landman Funny?

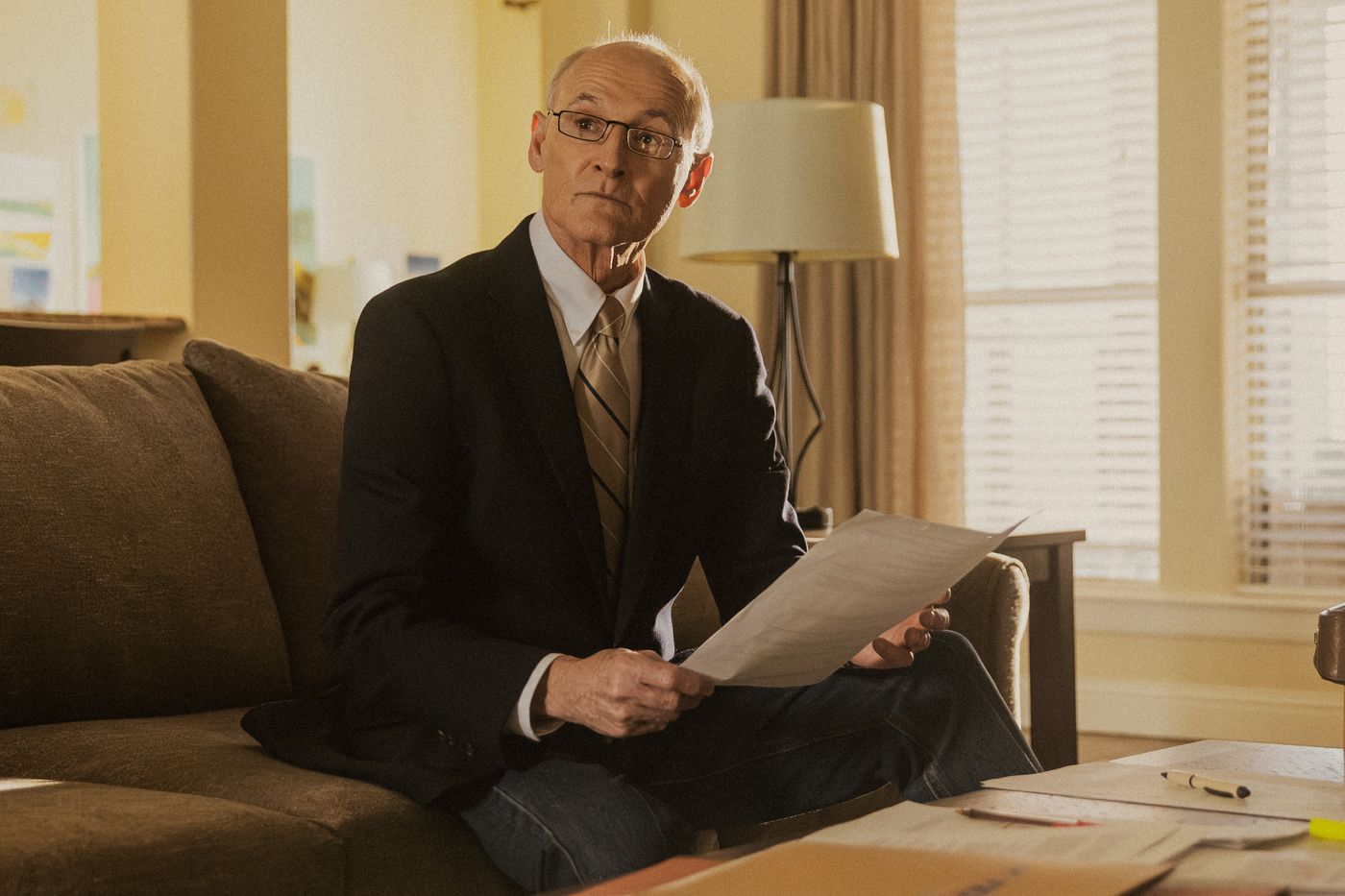

Taylor Sheridan’s latest may not have actual jokes, but it does have a perpetually cranky Billy Bob Thornton, and that might be enough.

Taylor Sheridan’s ever-sprawling TV dominance has inspired a number of questions. Which western-genre clichés will he tackle next? What’s the deal with this season of Yellowstone’s obsession with John Dutton’s death? Is there a reason he had to write himself into Lioness — and make his character shirtless? So many questions! And now, an important one for Vulture critics Roxana Hadadi and Nicholas Quah to ponder: Is his newest series, the Friday Night Lights–esque Landman, based on the podcast Boomtown and starring a perpetually cranky Billy Bob Thornton, funny? Is it meant to be funny? What is a joke to Taylor Sheridan, anyway?

Nicholas Quah: In many ways, Landman is the chillest entry in the Sheridan-verse, which is typically packed with violence, melancholia, and dudely grouchiness. There’s still plenty of all that in this show, but it’s also seemingly the guy’s take on a lighter dramedy. Or something more family-oriented, I think. Halfway through this season, I admit I’m still unsure. Roxana, what’s your read on what Sheridan is trying to do with Landman?

Roxana Hadadi: It’s weird! It’s weird because half of this show is Sheridan doing his typical “let me defend the forgotten American” thing, so oil-company fixer Tommy, played by Thornton, is constantly breaking into speeches about how important oil is to our economy and how silly it is to think we can replace it. And if you don’t believe it from BB, maybe you will from Jon Hamm, who shows up every so often as M-Tex head honcho Monty to look hot and give “Don Draper but evil” speeches.

Some of that stuff is meant to be funny, I think, for an audience who comes to Landman already aligned with its men-are-smart, oil-is-good worldview. They’re not jokes so much as scenarios that invite a derisive jeer or scornful laugh. Like in the premiere, when Tommy — whom the show has already established as a good old boy who’s more resourceful and pragmatic than the cartel members who hold him hostage and then let him go when he explains how they can make more money by working together — listens to a radio report about oil prices. He condescendingly talks back to the female reporter during her segment, which conveniently has pauses built in so he can do this, rejecting her reporting and calling her “honey” as he scoffs at her observations. He’s ultimately impressed when, at the end of the segment, she shares an opinion that aligns with his, but that’s not because she wowed him, it’s because she said what he wanted to hear. The scene invites viewers to join Tommy in rolling their eyes at the idea that a journalist — a woman journalist, no less — would have any idea what she’s talking about, and I find sardonic humor in how baldly sexist this setup is in asserting Tommy’s superiority.

That’s basically the same approach Sheridan’s using for the other half of this show, which is about Tommy’s domestic dramas: He has a “teen” daughter, Ainsley (Michelle Randolph, the actress playing her, is very clearly 27 years old), who decides she wants to live with him in a house he rents with two other M-Tex employees, and an ex-wife, Angela (Ali Larter, giving it her all as a cool mom), who is still obsessed with him and wants to get back together. Ainsley tells Tommy that her arrangement with her hotshot quarterback boyfriend is that “As long as he never comes in me, he can come anywhere on me.” Angela takes her clothes off in the middle of a country club’s restaurant to show Tommy her banging body and remind him what he’s been missing. Neither of these women acts like a real person, and the family stuff involving them boils down to “Bitches be crazy” … and, well, some of it makes me laugh despite myself, not just for how nonsensical it all is, but also for how it allows Thornton to reply with Bad Santa–like deadpan. His general vibe on this show is exhausted and sarcastic, and that approach won me over, even as the content of his exhaustion and sarcasm is pretty gross. Nick, are you laughing intentionally, or against your will?

NQ: I don’t think I laugh out loud at the show so much as feel vaguely amused. Sure, yes, comedy is a subjective thing, but Landman has mostly struck me as being funny in the theoretical sense. I can see discrete scenes, lines, and situations written with the overt intention of drawing a chuckle: When Tommy ends up dining with his daughter, ex-wife, and the much younger lawyer he may or may not end up having a thing with, you can broadly see the shape of a humorously awkward situation. Or take any number of Tommy’s retorts, like a little moment in the third episode when he chafes at being told not to smoke on the patio of Monty’s country club, which is outdoors. (This draws from a Sheridan go-to of having characters complain about policies that seem inane to Sheridan personally: In the very first episode of Yellowstone, Beth Dutton has a similar gripe about not being allowed to smoke in a hotel bar that’s full of burning fireplaces. Civilization and its discontents, you know?) But these scenes don’t build to punch lines that actually punch, and they rarely follow through on comic situations in a way that draws out a discernible laugh.

But I don’t want to sit around and litigate individual comedic ideas. What’s interesting here is less what I think is funny and more what Sheridan generally thinks is funny. Roxana, help me unpack the guy’s humor, starting with Nathan, Tommy’s sad, unfortunate lawyer colleague who also happens to be his roommate. He seems to be the most obvious comedic vessel.

RH: Colm Feore, from my beloved Chronicles of Riddick! Yes, he’s the series’ resident cuck and Sheridan’s clearest attempt at humor, and that humor is: Look at how difficult it is to be a gentleman these days in the face of women and their antics.

Ainsley and Nathan’s interactions are fascinating because she’s supposed to be a high-school senior who walks half-naked around this house she, for some reason, wants to share with three older men. Nathan is scandalized by this while the show is titillated. (The camera lingers on Ainsley’s butt a lot.) That dynamic renews when Angela moves in, too, and the women do highly sexualized workouts while Nathan is trying to work. The joke here is that Nathan is a frazzled dweeb (rather than being as cool as a cowboy played by Sheridan who challenges women to strip poker), but the real point is that women just can’t stay out of the way of men’s business — and that’s such a silly, Sheridan-esque take that I am once again sardonically laughing. This is why open-concept layouts are bad! Especially when your co-worker’s ex-wife is telling you, unsolicited, about how she has to keep her peach plump!

Both at home and at work, the series just keeps relying on this soft misogyny for awkward situations where the audience is meant to laugh at female characters’ immaturity or unearned boastfulness. The only exception I can think of is in a scene where Tommy’s lawyer Rebecca tears into opposing counsel for infantilizing her — but then we learn that she was lying about her father’s tragic military backstory to score points in the fight, so we’re still returning to a baseline of “don’t trust women.”

NQ: Sheridan’s sense of humor is fairly simple to begin with. This isn’t a knock: A broad laugh is a broad laugh. But what’s tough to digest is how so much of that simplicity is tied to the whole misogyny thing — and it is misogyny, no doubt about it. In addition to being some weird expression of daddy-daughter shit that Sheridan is clearly obsessed with, Ainsley is such a difficult character to defend as a creation: an excessively sexualized teenage daughter, played by an obviously older woman, who’s perpetually scantily clad around older men. It’s just icky. (Meanwhile, Demi Moore, who’s having quite the year with The Substance, is just floating around as Monty’s wife, doing absolutely nothing other than swimming, going to fancy dinners, and telling her husband he’s had too much coffee.)

Exacerbating all this is the fact that Landman, not unlike the rest of the Sheridan-verse, is all over the place in terms of tone and emphasis such that you can never really get a clear sense of what Sheridan is trying to do with any particular choice. What does he actually think about the mythology of boomtowns? Is it bullshit? Noble? Idealized? It’s all muddled, which is par for the course with Sheridan; his writing hasn’t been thematically sharp since Hell or High Water.

One thing’s for sure, though: Sheridan loves to complain about stuff. Aggrievement is his essential fuel, the oil that produces all his products. Take the whole scene with Monty on the golf course, where he’s setting up a swing and delivers a big monologue about not letting other golfers play through because they’ll gum things up. I’m sure it’s supposed to show Monty’s big-boy nature, but it also just seems like Sheridan the writer getting something off his chest about the last time someone played through his own time on a green. That, I find kinda funny.

RH: I love Monty complaining. Jon Hamm telling someone they suck to their face is my happy place. But you’re right that Sheridan’s pattern in Landman is to give his male characters these exposition dumps that seemingly align with his own opinions, and because of the show’s oil-industry milieu, that means Tommy and Monty are often defending their business practices. I’m thinking of when Tommy tears into Rebecca, the lawyer he asked Monty to hire to defend M-Tex from a potential liability lawsuit, because she dares suggest that alternative energy is the future. After a solid three or so minutes of Tommy telling Rebecca that oil is in an array of consumer products that will never disappear from the marketplace, the scene ends with one of those odd tonal pivots you mentioned: Tommy walks away from their conversation and leaves Rebecca alone in the overgrown scrubby field, where she’s threatened by a rattlesnake. This woman we’ve been told is an extremely capable lawyer simply melts down and begs Tommy for his help, and then is shocked and whiny when Tommy kills the snake to protect her from it.

I think this is meant to be a jab at bleeding-heart liberals, or something? If I weren’t so charmed by Thornton’s wiseass line delivery and general presence on this show, I’d be pretty irritated. And to be fair, I was pretty irritated when Tommy asked Angela if she was on her period in this week’s episode. (Unless you’re What We Do in the Shadows using that question to demonstrate a vampire’s cluelessness about his wife’s undead anatomy, leave that shtick in the ’90s.) But I must admit he’s giving this dubious material an appealingly sarcastic edge that another Sheridan joint like, say, Lioness lacks. Is Billy Bob dryly complaining about his popped hemorrhoids at a family dinner enough to keep you watching, Nick?

NQ: You know, I think it might be. I’m enjoying the competency and tonal steadiness that Thornton brings to this show, which illustrates another recurring thread across the Sheridan-verse: The entries that land best are the ones with the right actors transcending the material they’re given. Landman really benefits from Thornton being a pleasure to watch bop around, look sweaty, rant about the state of America, and generally express a state of existential exhaustion.

To loop back to the original question driving this conversation: I’d like to submit that the funniest thing Sheridan ever wrote is the entirety of Beth Dutton as a character. Everything about her is hilarious to me: how she speaks, how she looks, how she goes about doing things. But all that funniness is inadvertent — I don’t believe Sheridan intended her to be Yellowstone’s Queen Camp Supreme — and I think Thornton’s work on Landman is another instance in which the right actor transcends the script. So maybe that’s a good shorthand for Sheridan and comedy. When he’s trying to be funny, it usually lands with a thud. When his threadbare scripts give capable actors room to find their own pockets of comedy, you can occasionally bump into the sublime.

Related