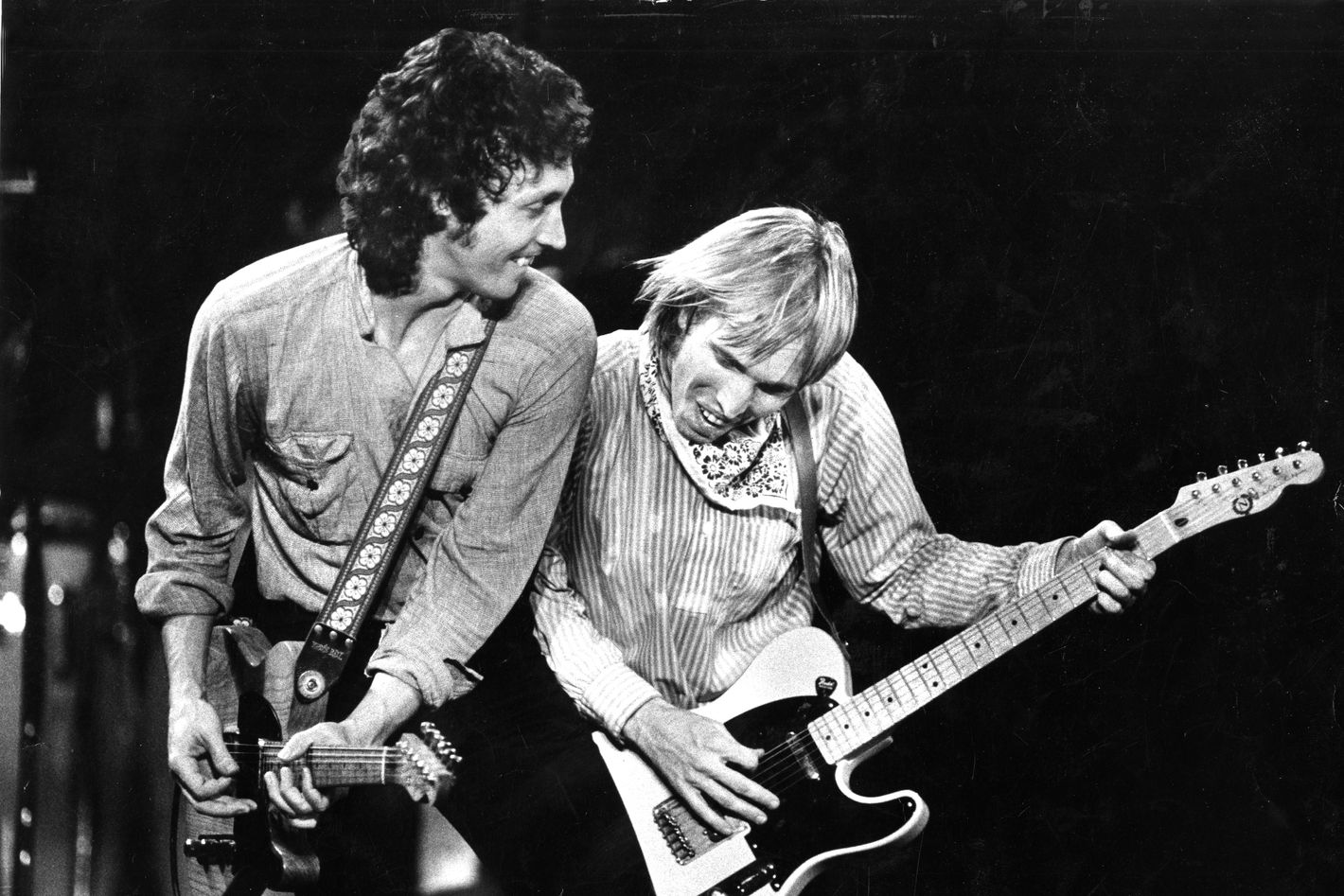

Mike Campbell Doesn’t Know How He Got So Lucky

The Heartbreaker on his unspoken bond with Tom Petty, “sideman syndrome,” and Bob Dylan being jealous of “The Boys of Summer.”

Mike Campbell is a phenomenal guitar player whose prolificacy could bring many of his peers to shame. But what I took away most from Heartbreaker, his new memoir, was how much of a mediator he was. Some of the book’s most endearing stories are when Campbell, closely associated with Tom Petty, worked alongside and elevated the careers of legends such as Bob Dylan, George Harrison, and Don Henley — all of whom benefited from his improvisational playing style and seemingly never-ending supply of songs.

Heartbreaker begins with Campbell climbing out of poverty in Gainesville, Florida, thanks to his guitar skills. (“I played like my life depended on it,” he writes on more than one occasion.) He met Petty while in college; Campbell believed in him enough to become a proud dropout. After several false starts, the duo — along with Benmont Tench, Stan Lynch, and Ron Blair — formed the Heartbreakers in 1976, and their country-unifying, dream-running sound eventually propelled them to stardom. Even now, at 75 years old, Campbell still can’t believe his luck. “Very few people get all those blessings that came to me,” he recently told me over coffee at the Carlyle hotel. “Without getting too philosophical, there’s some kind of magic destiny out there for certain people who are in the right place at the right time, and I was one of those people. It’s kind of scary.”

You famously have the opposite of whatever writer’s block is. So what took so long to translate that into a memoir?

I wasn’t ever planning on doing one. I was going about my business and Jaan Uhelszki, a friend who started Creem, approached me with a ghostwriter. She said, “You should write a rock book.” I wasn’t really that interested in it. Besides, I don’t like nostalgia. I don’t look back at old memories. Sometimes it makes me sad. But she talked me into it, and I enjoyed the process.

How did you arrive at that stance on nostalgia?

Bob Dylan once said something that resonated with me: “Nostalgia is death.” I know what he means. You get stuck in the past. If I’m looking back, I fear I’m missing out on what I could be doing now.

A lot of reporting about the book has focused on the heaviness of your and Tom’s relationship, but what I took away most is the image-making you did for yourself and other artists. When did you realize you had this magic touch of earning the trust of artists who aren’t known for being too trusting?

I’m shy and I’ve mostly worked inside my own little group. But one day Jimmy Iovine guided my name to Don Henley, so I spoke to Don and he wanted a song that would define his solo career. I thought, I’ll try to conjure that up for you, whatever that means. There was magic in the air with “The Boys of Summer.” But why? I don’t know. There’s nothing special about me. There are a million guitar players and songwriters who are all really good. I’ve just been in the right place at the right time.

There’s a passage about opening for Kiss in the Heartbreakers’ early days, where Gene Simmons gives you useful advice about the rules of rock and roll. Geddy Lee wrote about a similar experience in his memoir, so there’s clearly a Kiss trickle-down effect.

For that tour, we were nobodies. Our gigs leading up to that were playing in sawdust places on the floor — it was awful. We arrived at the venue and the band came in wearing their robes like heroes. Gene is standing in the hallway and I didn’t think he would even talk to me, nonetheless give me a lecture. I said, “What are you guys doing here?” We were in a very small town somewhere in the South on a weekday. Not exactly a place you would expect to see Kiss. He looked at me and said, “Listen, kid,” and went right into it. He told me all about honoring the markets. He was like a professor.

I loved reading about Bob Dylan’s reaction to “The Boys of Summer” and how its sheer greatness made him say, “I wouldn’t mind having a big hit, too.” Did this reaction surprise you?

Yes, but everything Bob says surprises me. He’s an enigma wrapped in a puzzle. I was at a session one day and he told me, “Wow, ‘The Boys of Summer’ is a big hit. Did you use the drum machine on that? Do you still have it?” I said, “Yeah.” And he went, “Could you bring it down tomorrow? I’d like to have a hit, too.” In his mind, I’m the same guy who did it, so it would work for him.

So you actually tried to get him that hit. Why didn’t it work?

He didn’t play along with the drum machine and got frustrated. I don’t know how he didn’t comprehend that. He was playing freestyle. After a few minutes Bob and the engineer look over at me, and Bob goes, “That doesn’t sound right.” He looked at me like it’s my fault. I said, “Well, Bob, when you turn the machine on, you have to follow it so the record is on beat with that.” And he responds, “You mean it won’t follow me? Well, what good is it?” He was dead serious. I thought that was the most illuminating thing about Bob. He had Jim Keltner, Ringo Starr, Levon Helm, and all of these great people in the studio and still felt he needed the drum machine. It’s a thin line between child and genius. I love the guy.

You describe the tour the Heartbreakers underwent with Bob as a transformative experience. What fulfilled you from this particular tour that you were unable to get from other periods of time on the road?

It was liberating, because we learned a lot of songs and it was a totally different work ethic than the Heartbreakers. The Heartbreakers honed into showbiz. You get a set list, there’s an arc, you whip the audience into a frenzy and engage them — the whole thing. Bob doesn’t do any of that. He can do what he wants to do and the audience can boo, clap, leave, or smile. The Heartbreakers would never. It takes a lot of courage to perform that way, but it keeps you on your toes and I like that about Bob. It was also good for Tom to sit back and not have to carry that whole weight of the tour.

You wrote that your proudest moment as a guitarist is a solo you didn’t play on, the Traveling Wilburys’ “Handle With Care,” because you convinced George Harrison to do it instead — even after you recorded your part. Tell me what you consider your second-proudest moment.

Coming up with the guitar parts of “The Boys of Summer.” I was proud that the song happened in stages and the guitar parts didn’t all come together at one moment. I still love it when I hear it on the radio. But it’s not as good as the solo I didn’t play.

Is there anyone you were hoping would call you to pillage your song shelves who never did?

Bob once came over to my house because he wanted to write a song. The first thing he said was, “Do you have any lyrics?” I’m not joking. It was hilarious. I had never written a lyric in my life. That was a big deal, even if the song never worked out. I would like to have worked with John Lennon or Paul McCartney. Oh, Keith Richards. But they don’t need me. Who’s left who would be inspiring to me? I’m not into the younger kids as much. It would be old people. If Carole King called me, I would jump through the window. If Justin Bieber called me, I’d probably say, “I don’t think I’m right for you.” I’m not waiting on any call. I’m busy. Don’t call me.

What has your relationship been with the term “sideman syndrome?”

My perception of it hasn’t changed over the years. To me, a sideman is the guy in the band who’s literally on the side. He doesn’t sing — he sits back and plays. Their job is to support the star. Even though I’m in the Heartbreakers, I wasn’t the main guy. Tom used to call me the co-captain, but the rest of the band never felt like sidemen. We were partners in a band. It’s a different mentality. That’s one reason Tom kept the band together for so long. I’m the same now. There’s no sidemen in my band, we’re all together. I might be doing most of the work, I might make a little bit more because I’m working harder, but you guys aren’t my sidemen, you’re my partners.

You write how, time after time, Tom heard things in you that you couldn’t hear in yourself. What were some of those things?

He and I were dudes. We didn’t talk about feelings or have “what I think about you” conversations. There was no other way other than, “I like that guitar part. That was a great gig.” He trusted me that if he brought a sketch of something, I would sit down with him and make it better than he could have done on his own, and vice versa. Listen, it’s a powerful thing to trust. It’s a big thing with musicians. He must have seen a talent and a musical canvas that I could bring to his writing. Tom wrote a lot of simple songs. My musical awareness is very wide. I know classical music, different chord moves, and stuff that’s a little more complicated. He may not have known all of that. So I think he appreciated that I had a musical palette that was wider than his.

What did you hear in Tom that he couldn’t for himself?

He appreciated that I respected his privacy when we were off the road. We would go to our homes, our wives, be apart and not talk for six months, then he would call me on the phone and we would talk for hours. We didn’t have to socialize during off-hours, and he liked that I wasn’t in his space all the time. I never asked him, “Hey, what do you really think of me?” But I know he liked me.

Was there ever a fear that the trust was broken?

We might be a little pissy with each other over something stupid, like a snare sound, but nothing was ever like, Oh man, I can’t work with this guy. There was a time when I decided to show him some songs I was trying to learn and sing as a solo artist. That was a little delicate. He was truthful in his own backhanded way and said they were terrible. He called me the next day and said, “I’m sorry. I was on the wrong pills.” What I liked about Tom is he was straight. He didn’t sugarcoat stuff. I kind of winced for a second, but then I thought about it later and I’m glad I didn’t put that record out at that time. It wasn’t good enough.

A glaring omission in this memoir is that you don’t elaborate when your taste for fine headwear began. Care to clear that up?

When my hair started to look bad. I liked the idea of: Did you put on your coat? Did you put on your shoes? Did you put on your hat? It’s your identity. It makes you feel in the zone. Then people would come up and tell me, “That’s a great hat.” So I started collecting them. Sometimes I’ll think, I look pretty good today. I’ll go without the hat. Then my wife will go, “Get the hat. Everybody expects to see you wearing the hat, it’s your thing now.” I’ve recently been working with Linda Perry, another artist who favors a lot of headwear. We’ve almost got an entire album of material without even intending to make one. So she asked me, “What are we going to call the album?” And I said, “How about The Hats?”

Related