The Studio Laughs to Keep From Crying

Beneath the broad farce of this Hollywood satire lies wistful nostalgia for an industry in decline.

Showbiz satire The Studio pulls off an anatomical feat, shoving its head so far up its own ass that it comes out the other side resembling something genuine and heartfelt. This is by design. There isn’t exactly a shortage of TV shows sending up the insipidness of Hollywood, from The Other Two to Barry to last year’s Armando Iannucci–produced The Franchise, but what distinguishes Apple TV+’s new half-hour comedy is its choice to marry farce with a palpable warmth toward the world it lampoons. There’s a real honesty to the resulting mixture: Yes, Hollywood is a silly, destructive business that deserves ridicule in so many ways, and yet there’s something about it that continues to inspire our deep, abiding love.

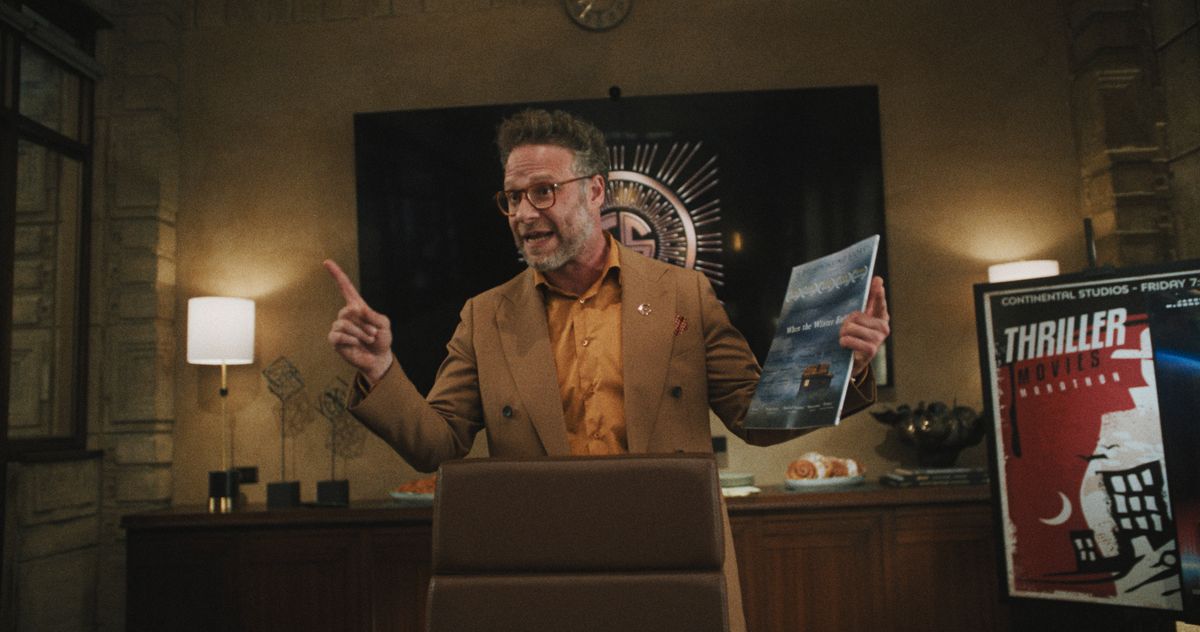

Personifying this contradiction is Seth Rogen’s Matt Remick, a sweaty film executive who at the outset of the series is suddenly elevated to the head of the titular Continental Studios. Remick fashions himself as a lover of cinéma powered by a belief that art and commerce can coexist to create great work: We hear him utter romanticizing platitudes about the movie business, we see him unwind after a long and disastrous day by watching Goodfellas, we watch him advocate for the idea that commercial proceeds can fund the true creative swings. Which is to say, of course, that Remick is the fool whose dreams will be stomped on throughout The Studio.

“I’ve heard you’re really into artsy-fartsy filmmaking bullshit,” says Continental’s mustachioed CEO, played by Bryan Cranston. “Rather than being obsessed with making this studio as much money as possible.” So it is that Remick spends the season toiling in professional and existential misery as he navigates the indignities of managing a major modern movie studio, like being tasked to build out a Kool-Aid film franchise to rival Barbie or defending the artistic integrity of a new Spike Jonze film featuring diarrheal zombies. And because Remick is also an insecure sad sack who desperately covets recognition, his personal inadequacies prevent him from doing anything particularly well. Averse to conflict, he labors to pass off the more difficult tasks — backstabbing Martin Scorsese or telling Anthony Mackie that the ending of his movie is bad — to his confederates, including Sal Saperstein (Ike Barinholtz), his caddish second-in-command; Quinn (Chase Sui Wonders), a young creative executive; Maya (an inexplicable Kathryn Hahn), a marketing chief desperately cosplaying youth-cool; and Patty (Catherine O’Hara), the mentor he usurped. It’s never a question whether Remick will realize his dream of marshaling the studio’s resources to champion art — he won’t — but there’s grim pleasure in watching the man rail against the cold hard truth that he’s nothing more than a bean counter.

The Studio hails from the Entourage and Silicon Valley school of insidery satire, meaning it can verge on being a little too knowing. The series bursts with cameos big and small: Aside from Scorsese and Mackie, you’ll also find Olivia Wilde, Ron Howard, and Charlize Theron, among others, all cast as themselves in ways that play around with their public personas to some extent. Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos pops up, too, making a fascinating appearance in streaming-enemy territory, as does the Hollywood insider Matt Belloni, whose presence underlines The Studio’s adeptness at conveying the feeling of Tinseltown as a weird, insular club.

But just as you might turn away from the showbiz chumminess of it all, The Studio keeps you hooked with two things. The first is a sheer sense of technical audacity. This is a sitcom at heart, so each episode yields a different problem for its crew to work through. But in some cases, the show explodes the scenario with a dazzling filmmaking conceit, as in the second installment, which features a visit to a Sarah Polley movie set on the evening her team is scheduled to pull off an ambitious one-take scene … and which itself turns out to be an episode-length oner. The fourth episode, in which Remick deals with a missing reel of film on the set of a neo-noir, is itself a loving homage to the genre. Sure, these gambits can sound too cute by half on paper, but The Studio pulls them off with such gusto you can’t help but be charmed. Also helpful is the show’s other winning quality: an enthusiastic embrace of its own stupidity. The Studio doesn’t lead with wry, ironic cleverness. Indeed, it’s happy to be a broad comedy with a broad protagonist that commits to the silliness of its universe, burrowing so deep into its comedic setups that it usually finds new laughs to extract.

A tempo of chaotic escalation recurs throughout The Studio with its particular humor hinging on the double-down. This is exemplified in a mid-season episode that sees Remick and an oncologist played by Rebecca Hall attending a medical charity gala, where the comedic tension arises from contrasting the vapidity of Remick’s job against the more overtly valuable work of medicine. Being a Hollywood romantic (and deeply insecure), Remick can’t help himself when his fellow gala attendees condescend to him. So he commits, again and again, to arguing for the societal value of the entertainment business, a notion that’s theoretically true but also laughable in the face of, you know, cancer research. As Remick clings to his miserable self-importance, there’s a circular effect: His insistence is at first broadly funny, then cringe-inducing, then, as he continues to advocate and escalate, rote and annoying — only to finally become funny again. It’s reminiscent of the old “Kristen Schaal is a horse” bit, in which repetition becomes the primary engine of loopy humor, and at some point, your brain begins to submit to the commitment on display.

The Studio’s comedic default is to simulate the conditions of a heart attack induced by stress, disaster, and embarrassment, which it augments with a directorial eye that keeps both the characters and the camera perpetually in motion. Rogen does impressive work juggling multiple duties; in addition to starring, producing, and writing, he co-directs all episodes with frequent collaborator Evan Goldberg. (They share creator credit with Peter Huyck, Alex Gregory, and Frida Perez.) Notably, they favor a visual style evocative of the New Hollywood films from the mid-’60s to early ’80s that Remick worships. You can potentially discern a thematic idea in this aesthetic choice, given how that era coincided with the decline of the Golden Age studio system, itself precipitated by the rise of, well, television. There’s a kind of implicit prayer in this that the withering of today’s Hollywood system is a presage for something better, giving the entire production a painful, nostalgic quality that tugs at your chest even as what unfolds before you is remarkably dumb.

This wistful sensibility also peeks through whenever The Studio takes a beat to soak in the beauty of Los Angeles, as it does at the end of the pilot, when Remick and Patty hang out in the yard of her gorgeous manse in the Hills. That image is a little haunting today, given the city’s recent wildfire carnage, but that emergent feeling adds to the haunted mood pervading The Studio. As much as the series carries itself as a farce populated by dolts, it also conveys a sadness that its subject’s best years are likely behind it. “I’m like 30 years too late to this fucking industry,” Quinn, the young exec, bemoans early in the series. One episode late in the season, which features the Continental crew at the Golden Globes, has a quick gag in which Remick is confronted by influencers on the red carpet, prompting him to wonder, “Fuck is happening to this town?” These sentiments are delivered as jokes, but they nevertheless carry a tinge of true heartache. It’s trite to describe The Studio as a love letter to Hollywood; that would be far too clichéd for a show this self-aware. Rather, in its warm embrace of an industry in decline, what The Studio actually resembles is a postcard from the end of an empire.