OK Go Are Still on the Treadmill

They were the first musicians to bet big on YouTube. But their approach continues to raise questions about what it means to be a band.

On January 16, OK Go premiered a new song, which is to say they premiered a new video. Made up of 64 individual clips, loaded onto 64 iPhones, “A Stone Only Rolls Downhill” created a sort of choreographed mosaic of the band’s members, dressed in colorful monochromes, lip-syncing to the first single off their first album in over a decade. While a few news outlets acknowledged the music, the vast majority of headlines unsurprisingly focused on the stunt itself. Rolling Stone: “OK Go + 64 Phones = New Video.” Fast Company: “OK Go’s new music video is 64 phones of pure joy.” Stereogum: “OK Go Unveil Latest Music Video Stunt 20 Years After Breakthrough Viral Video.”

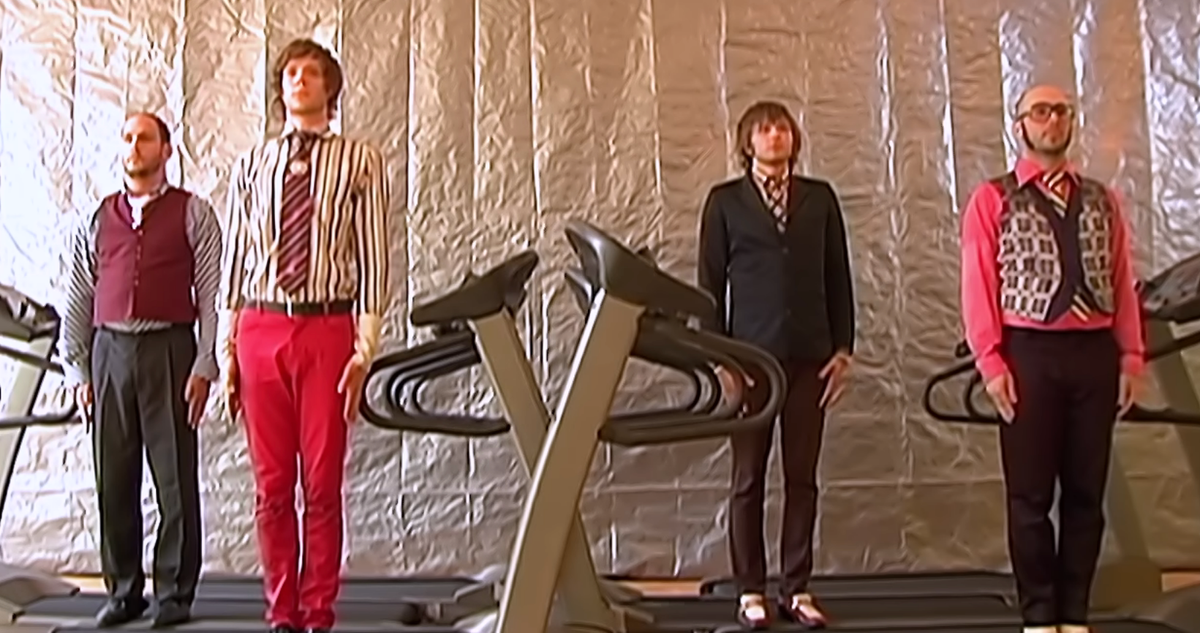

OK Go’s reputation for offbeat clips was built in the 2000s, when the group became synonymous with the first generation of YouTube. By the time they posted 2006’s “Here It Goes Again” — famous for its tightly choreographed treadmill dance — videos were already going viral online, like “Lazy Sunday.” What was new was making work specifically for YouTube itself. OK Go’s video would garner a then-impressive million views in 24 hours and become the most-played clip on both VH1 and MTV. At the start of the year, OK Go were an obscure rock band; a month after “Here It Goes Again” dropped, they were performing their treadmill routine on the VMAs.

In truth, the band was always better at filming quirky stunts than writing songs, with their first few albums of indie-glam power-pop poorly received. (Pitchfork’s 2.2 review of 2005’s Oh No: “OK Go decide to impersonate post-Pinkerton, post-catchy, fun-by-numbers Weezer, resulting in an Ivy Leaguer Sugar Ray sound.”) The videos they made consistently went viral at a time when many creators and corporations were desperately trying and failing to do so. “If Nirvana ushered in the grunge generation, it seemed like OK Go ushered in playing videos on the Internet,” director Samuel Bayer (“Smells Like Teen Spirit,” “No Rain”) once told New York. The head of marketing at Apple later called OK Go “the first post-internet band.” But really the internet allowed OK Go to be a post-music band. They went on to become what now would be considered content creators: artists geared toward sharing art on digital platforms, where the work and promotion of the work is intertwined.

From the start, OK Go had a desire to goof around, but they first had to get over the need to be taken seriously as musicians. Before YouTube existed, Ira Glass invited them to perform at a few live productions of This American Life in 2000, where he asked lead singer Damian Kulash to explain the band’s mission. “Do you see yourselves as being earnest or clever?” Kulash later told the Chicago Reader that he felt stuck by the question: “Clever is the last thing you want to describe yourself as — this annoying, quirky thing — and earnest has this connotation of drippy faux sincerity.” But Kulash eventually chose earnestness: “I wrote a lot of songs that I wanted to actually believe in … I didn’t want them to be ironic or distanced. I wanted to write songs that would be uncomfortable in an indie-rock club, songs that would require a stadium.” Earnestness for OK Go was initially just to be a classic band fully committed to expressing themselves through song, not cleverly poking fun at the self-seriousness of professionally making music.

Those ambitions came through with their debut single, “Get Over It,” which garnered the group a deal with a major label. As was the trend, OK Go’s music was horny, straightforward, garage-y rock, and the videos that went along with it were similarly paint-by-numbers. Any of the clips created to promote their self-titled debut could have been made by any other similar artist. If you didn’t know it, you’d think you were watching Jet.

However, by the next album cycle, they started taking a turn toward the fun, gimmicky approach they would become known for. For “A Million Ways,” the first single off their sophomore album, the label had them film a big-budget video for the song. But Kulash preferred a scrappier version they’d shot instead, where they did a cute choreographed dance in a random backyard. But the label wouldn’t release it, allegedly calling it “gay” and “career suicide.” So Kulash leaked the clip to fans, who uploaded it to the internet in a pre-YouTube window when videos went viral by being downloaded off other websites and file-sharing platforms. It was harder to quantify things back then, but, after a year, both views and downloads were in the millions. Talking to NPR, Kulash said, “This video accidentally captured how excited we are to do this stuff. We don’t take ourselves too seriously, but we take what we do really seriously.” In response, All Things Considered host Robert Siegel, acknowledging a similar dichotomy to his colleague Glass, said they struck “the perfect balance of the earnest and the ironic.” Kulash agreed.

Yet by 2010, the band began to change. After garnering attention with “A Million Ways” and “Here It Goes Again,” OK Go released the video for “This Too Shall Pass,” shifting their approach from earnest to clever. It was one thing to do a funny dance; it was another to employ 30 people to precisely engineer a whimsical Rube Goldberg machine. In turn, viewers were significantly more intrigued by how they made the fantastical contraption than the song that ostensibly inspired it. “We see [the videos] as endpoints, not ancillary promotional material,” Kulash told Mother Jones at the time.

From that point on, OK Go made videos that merely included songs they’d written. Saying they were better known for the videos than the music therein was a criticism they were seemingly fine with. In a 2018 episode of The Simpsons, an OK Go shoot goes wrong and the band members, each flying in the air on their own drone, come crashing to the ground. “Oh no, now people have to judge us for our music,” says Kulash, who voiced himself. Tim Nordwind, the band’s bass player, adds, “We’re doomed.”

Solidifying this dynamic was the fact that, after “Here It Goes Again,” those millions of views never translated to record sales. A week after the release of the “This Too Shall Pass” video, it had over 8 millions views on YouTube, but the album it appeared on, which had already been out for two months, hadn’t even sold 25,000 copies. A week later, the band announced it was leaving EMI, due to those poor sales and the label’s policy at the time, which made it impossible to embed its artists’ work on sites. As a result, OK Go found themselves in a position that would become common for content creators today: If you are not going to make money the traditional industry route, your options are either a patronage model or moving into sponsored content. OK Go did both; their last album, 2014’s Hungry Ghosts, was funded using a Kickstarter-type service called PledgeMusic. Meanwhile, State Farm sponsored “This Too Shall Pass”; Morton Salt sponsored the video for “The One Moment” (in which 4.2 seconds of explosions is slowed down to reveal a full production); and their video for “Upside Down & Inside Out,” filmed on a reduced zero-gravity aircraft, was bankrolled by Russia’s S7 Airlines. These companies were not sponsoring OK Go’s music, they were sponsoring their video-making, paying for OK Go to be clever, not earnest.

“A Stone Only Rolls Downhill” is as clever as any of their past work. It takes the commonplace idea of watching someone dance on a smart phone and ingeniously fractures the performance across multiple screens, resulting in something kooky and trippy. But tonally they are taking a different approach beyond that standard cleverness. They are still having fun with the idea of being a band, but they are no longer winking to the audience through charmingly clumsy execution. Maybe because the choreography is less madcap than we’ve come to expect from the guys, the overall feeling of the video becomes poignant and nostalgic, if not quaint. Seeing them do their funny little thing for the first time in more than ten years is reminiscent of a simpler time. Content creation isn’t like it was in OK Go’s prime; popularity on social video platforms now demand regularity. “This Too Shall Pass” took six months to make, where today audiences and apps are expecting daily releases, regardless of effort or quality. With success so determined by gaming algorithms, posting on TikTok and Instagram Reels and YouTube demands cynicism. In retrospect, OK Go’s clever videos feel, well, earnest.

Related