Sabra Isn’t Controversial in Captain America: Brave New World. She’s Boring.

Why adapt an Israeli superhero destined for controversy and then just avoid defining her at all?

She looks like the Israeli flag on disco night. Blue cape, white bodysuit. A headband, because it’s 1980. The Incredible Hulk #256 introduces Sabra, “super heroine of the State of Israel,” when the green Goliath rampages through Tel Aviv. Airborne in a costume spangled with six-pointed stars, she fires poisonous “energy quills.” (An editor’s note explains that “Sabra,” a local prickly pear, is slang for “native-born Israeli.”) She accuses Hulk of an alliance with masked Muslim terrorists who blow up a café. The superhumans argue over the body of Sahad, a friendly young pickpocket killed in the explosion.

“Boy died because boy’s people and yours both want to own land!” Hulk yells. “Boy died because you wouldn’t share!”

Sabra, chastened, kneels by the small corpse. “It has taken the Hulk to make her see this dead Arab boy as a human being,” the closing narration reads. “It has taken a monster to awaken her own sense of humanity.”

Forty-five years later, Sabra makes her film debut in Captain America: Brave New World. She has no powers and no costume, unless you count some blue flair on her jacket. She works for America. Nobody calls her Sabra. Unorthodox star Shira Haas plays the reimagined Ruth as a “security adviser” to President Thaddeus Ross. She was born in Israel, we’re told, then trained as a Black Widow. After a couple fight scenes, she spends the climactic set pieces stranded on comm-links.

“None of us have to be defined by our past,” she tells Sam Wilson, New World’s new Cap. She’s nominally talking about her boss, but that line sounds like a plea. The movie does not want Ruth defined by her source material, her nationality, her comics history as a Mossad agent, or the furor around her inclusion that led to protests at this week’s premiere. The movie settles for worst-case-scenario defensiveness, refusing to define her at all.

Why adapt a character destined for controversy if you’re going to remove all her character traits? I suspect nobody at Marvel thought Sabra was controversial when Haas’s casting was announced in 2022. Devastation has followed devastation ever since. The Hamas attacks of October 7 led to Israel’s invasion of the Gaza Strip, while pro-Palestinian protests roiled American campuses. Brave New World’s makers certainly couldn’t imagine that, a week before their release date, the American president would declare plans to “take over” Gaza.

You sense rewrites, reshoots, retreat. Vulture’s Chris Lee reported how negative reactions to the rage-monster commander-in-chief led to cut scenes. Harrison Ford still has plenty of screen time, though, while Haas seems buried in a quick shift from vague antagonist to vague ally. No one could mistake her character for propaganda. No one will even remember her.

I feel semi-confident declaring Sabra was nobody’s favorite comics character. She only ever appeared occasionally as an anti-hero or Israel’s representative to the latest global-superhuman crossover. Any zealots seeking patriotic appeal would need to grapple with her default arc: a walking moral quagmire. Her first Hulk misadventure, written by Bill Mantlo and drawn by Sal Buscema, established her as an overreactive hard-liner. Later appearances often contrasted her with a jaunty Marvel icon’s moderating influence and an Islamic counterpart who exists to prove Not All Muslims Are Bad.

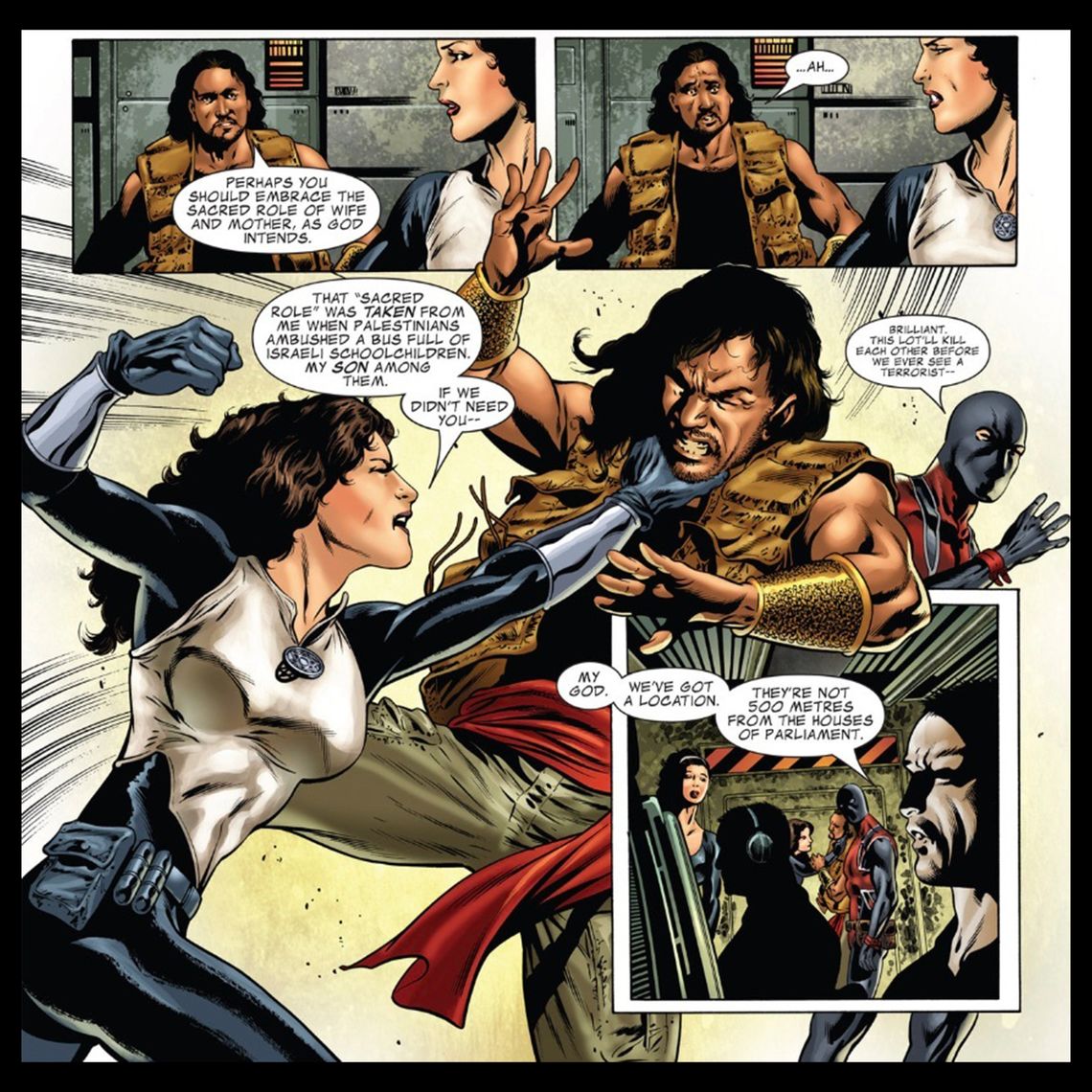

A month after first battling Sabra, Hulk meets the Arabian Knight, a desert chieftain with a sacred scimitar. Note the differing levels of cultural curiosity. Sabra has the Israeli national colors and her local moniker. (Her name and concept were conceived by Belinda Glass, wife of Marvel editor Mark Gruenwald.) The Arabian Knight has a flying carpet and a turban, as if a stripper service sent you Beefcake Prince of Persia. In his first adventure, he stops two ancient Egyptian demons from attacking Israel, but he was less diplomatic when meeting Sabra in 1982’s Contest of Champions, unwilling to “fight alongside a Jewess!” The political opponents form an uneasy alliance, a dynamic replayed in a 2006 miniseries where Sabra and another Arabian Knight help save London.

In between, a 1991 Incredible Hulk two-parter finds Hulk back in Israel to prevent the murder of a visiting European boy prophesied to grow into “the next Hitler.” Sabra again mistakes the monster for a foe. “I’m small and you’re huge,” she says, “But so is Israel small, and we stand up against our enemies!”

“Terrific,” Hulk says, “I’m not fighting a woman. I’m fighting the Zionist recruiting board.”

The young boy of prophecy gets trampled into a brain-dead coma. At which point we discover that the actual “next Hitler” is apparently his friend, a young Israeli girl whose father is a member of the Knesset. The writer of the issue was Peter David, a prolific genre storyteller whose own father fled the Nazis and who would later take to his website to compare the first Trump administration to Hitler. David mixes Sabra’s self-righteousness with something edgier. “Violence against women here,” she says, “it’s becoming commonplace. Frustrated soldiers are beating their wives because they had to stay their hand against Iraq. Our anger eats away even at ourselves.”

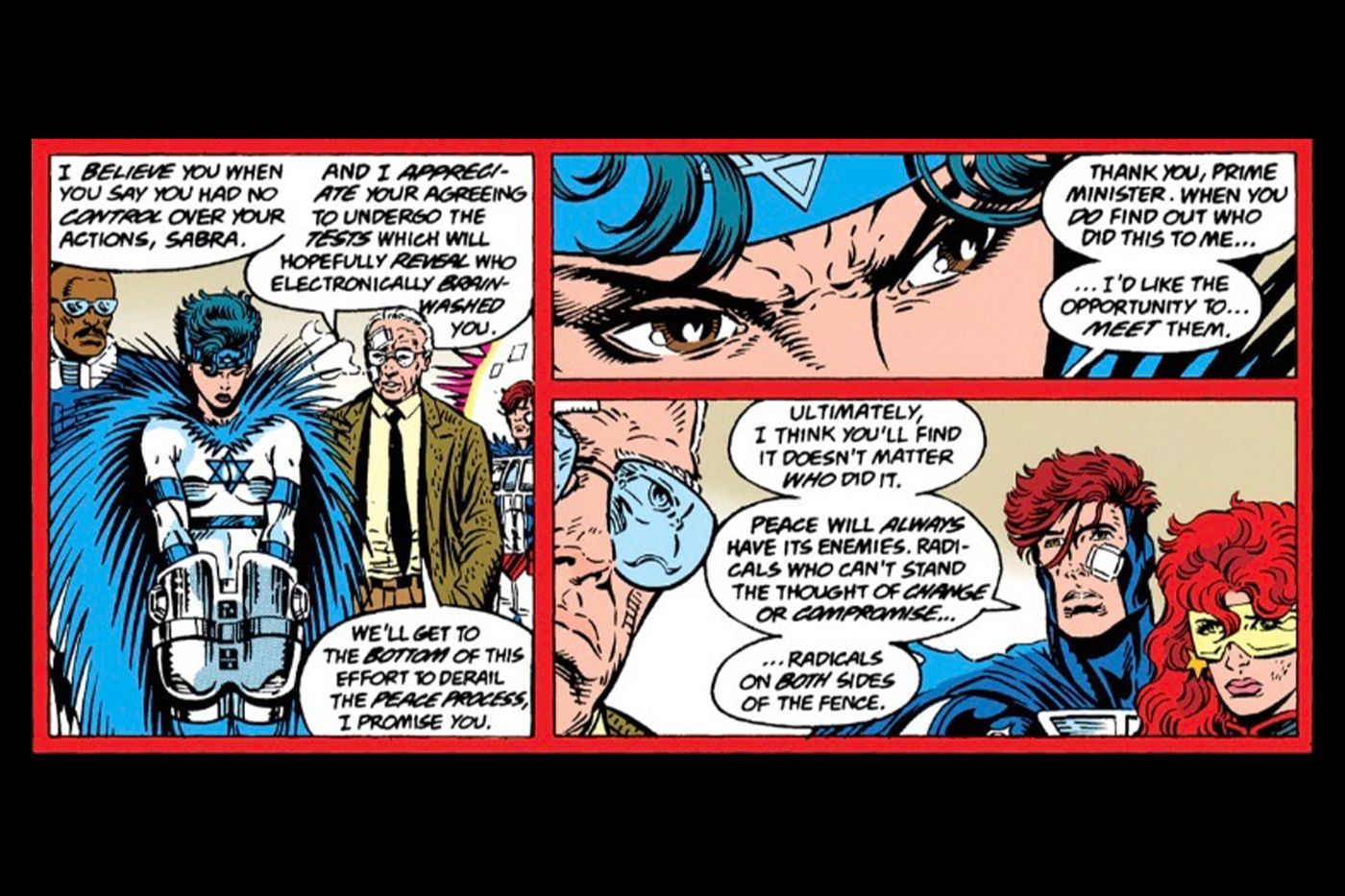

The girl in that story is “Izzy Rabin’s daughter,” presumably a reference to Yitzhak Rabin. He’s a central character in 1995’s New Warriors #58, attending a New York peace summit with Sabra as his bodyguard. By now, she has a blunt murdered-son backstory: “The Arabs killed him on his school bus.” Already vengeful, she’s mind-controlled into an assassination attempt on the prime minister (which mirrors a Brave New World subplot about hypnotized gunmen in the White House, though the movie’s Ruth never gets brainwashed). Local superhero Firestar theorizes Sabra could be “one of those radical Israelis who’s actually opposed to the peace talks.” It’s an upsetting story made entirely eerie when you recall Rabin was assassinated months later by a radical Israeli opposed to peace talks.

I’m not seeking secret genius in these ridiculous stories, and not even mentioning how pornish the illustrations get in the ’90s, with Sabra one of many superwomen drawn leggy and busty in the Image style. I understand anyone who thinks her tales are fundamentally broken, at best prone to a cheap fence-sitting and a distaste for any extremes. When Sabra learns an insta-lesson — five minutes with the Hulk awakens her humanity! — you sense the perspective of milquetoast American liberalism, a bit of why-can’t-we-get-along kumbaya. However sincere the writers’ humanist intentions, Sabra always gets more narrative prominence than the Muslim characters. Eventually, she was revealed as a mutant, one of Marvel’s many symbolic outcasts, a cheap way to ameliorate her very particular fraught geopolitical status. The character’s history is silly, tone-deaf, and rife with stereotypes.

Brave New World makes her something worse: Boring. On the page, Sabra was motivated by national pride. Onscreen, she has no motivation, quickly becoming an inessential secondary sidekick. (There’s a reason Bilge Ebiri doesn’t mention her at all in his lacerating review.) Making her a helpful ex-Widow is the ultimate cop-out, replacing complex real-world connections with generic globo-spy fantasy.

The Sabra situation mainly highlights the sharp contrast between the woolly frontiers of Marvel Comics and the frictionless corporate oversight of Marvel Studios. Do you prefer controversial incoherence or bland repetition, disagreeable politics or the sixth Black Widow clone? In this chaotic moment for America, the Middle East, and Earth, it’s notable how Brave New World resonates even less than some of Sabra’s ludicrous sagas of yesteryear. And in the comics, she never seems to stop anyone.

“Is whole world crazy?” a big green man says in the wreckage of Tel Aviv. “Is there nowhere Hulk can go to find peace?!” Yes, it is; no, there isn’t.