What the Hell Was Bartmania?

Thirty-five years ago, The Simpsons’s breakout underachiever became a controversy, and Matt Groening is still proud of it, man.

In 1990, Matt Groening arrived at his two-bedroom cottage in Venice, California, to discover the words “HOME OF BART” spray-painted across it in proud, unmissable letters. Groening’s first thought was, “How do they know I live here?” Which was followed quickly by the realization: “They didn’t.” And that was an indication of how popular his new show had become, “that my house could be targeted at random.”

“At least,” the Simpsons creator adds, speaking from his Santa Monica office in tones never far from jocularity, “I choose to think it was random.”

Random or not, the words were clearly a reference to Groening’s back-talking, trouble-making, prank-calling, cherry-bomb-detonating, and, yes, graffiti-tagging cartoon creation, who was at the time fast becoming a cultural icon. Thirty-five years ago today, in the Christmas special “Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire,” the world would meet Bart Simpson chanting “Jingle bells, Batman smells” at his school’s Christmas pageant and lying about his age in order to acquire two-thirds of a tattoo. But the first real shock of the episode, and hint of things to come, occurs when Bart greets a department-store Santa with his soon-to-be catchphrase, an insouciantly smart-assed declaration that promptly reverberated around the world: “I’m Bart Simpson. Who the hell are you?”

No one had seen anything like Bart on television before — not in a cartoon, not on a prime-time show, not in a family sitcom. In his conception of the character, Groening says he tapped into the frustrations he’d felt as a kid in the classroom, finding a belated outlet for the mischievous energy he’d mostly suppressed. The whole writing team were “Lisas who wanted to be Bart,” show writer Mike Reiss tells me. “We knew this was our breakout character. None of us were cool kids like him, but we could all relate to the iconoclasm.”

What Reiss, Groening, and the rest of the Simpsons crew couldn’t have anticipated was the extent to which everyone would proceed to have a collective cow. A mere few weeks into 1990, The Simpsons were everywhere: on the covers of TV Guide, Entertainment Weekly, Newsweek, and Rolling Stone (which profiled the family as if they were real), on Entertainment Tonight and The Larry King Show, and with your Burger King meal. That distinctive shade of yellow — a hue devised for maximum eye-catching impact — appeared on everything from bean bags to beach towels, T-shirts to talking toothbrushes, yo-yos to yarmulkes.

The Simpson-family scion was particularly inescapable: floating over parades in the streets of New York, singing on MTV, endorsing Butterfingers. In one Orlando high school, Bart ran for class president, and it was news when a 24-year-old Bexar County businessman named Bart Simpson said he was thinking about running for the District 115 House seat. (“I do have a name that people would recognize,” he said.) When the Simpson family presented at the Emmys, Bart repeatedly stole the spotlight, claiming an Outstanding Lead Actor nomination for “Bart Simpson for The Bart Simpson Show!”

At the time, it did indeed seem that modern life had been taken over by The Bart Simpson Show. A marketing rep from Amurol Products, who put out three Bart Simpson bubble gums that year, put it succinctly: “There is Bartmania out there.”

Bart was a national obsession, a flash point in the broader cultural conversations of the day about changing family dynamics, educational standards, and the evolving television landscape. For many, the Bartmania phenomenon was a garish horror show, the character himself an emblem of moral decay and a threat to society. A decade before The Sopranos, more than one publication dubbed Bart Simpson an “antihero.”

“I’ve never gotten so much angry mail,” executive producer Sam Simon told the Los Angeles Times in 1990. Speaking to me more recently, Reiss recalled a chastening encounter with an old classmate. “He comes up to me and says, ‘How can you put that garbage on TV? I’ve got kids to raise, man.’ And that really shocked me. I was really mortified.”

Today, Groening, still an executive producer on the show, talks about Bart and Bartmania in the manner of an indulgent parent, amused by the antics of his miscreant offspring. “To me, the greatest achievement of all is to have a large portion of your audience be completely offended by something,” he says between chuckles, “then another portion absolutely loving it.”

***

Bart as we know him, in his first act of impertinence, arrived slightly later than the other members of the Simpson family. In 1987, while waiting outside James L. Brooks’s office to pitch a cartoon for The Tracey Ullman Show, Groening hastily doodled a crude-looking family, naming the characters after his own father, mother, and sisters: Homer, Marge, Lisa, and Maggie. The boy was originally named after himself, “but I thought that was too egotistical. And that it might make it less likely for James L. Brooks’s production company, Gracie Films, to go for it if they thought it was autobiographical.” He decided on a name that was less soft, more spiky — a name that, in the voice of an angry parent, might take on the phonemic quality of a dog’s bark: Bart.

At first, Bart was unrecognizable as his future self, sporting an ill-defined cumulus cloud of hair. It was only later, when Klasky Csupo animation studio got the job by offering to animate the cartoon in color, that Groening realized he had to delineate where Bart’s hair ended. He came up with a much more striking silhouette: a jagged sawtooth look that suggested Johnny Rotten but could also be read as a hi-top fade. Even later, when the serration was softened by animation director David Silverman, there was an attitude in the look. Voice actor Nancy Cartwright, intending to audition for the part of Lisa, was more taken by the character description for Lisa’s older brother: “devious, underachieving, school-hating, irreverent, clever.” (Later, with her first pregnancy coinciding with the development of the series, Cartwright would plead with her unborn child: “Please don’t be Bart! Please don’t be Bart!”)

Groening suggests another word to describe Bart: bored. “I think he was like a lot of kids. He’s bored by school and, as a result, he acts out.” By his own account, Groening spent much of his childhood in Portland, Oregon, desperately keeping boredom at bay. On the first day of first grade, he took up doodling surreptitiously in the classroom. His whole drawing style — bulgy eyes, pronounced overbite — evolved from what he could do without looking at the page, while trying to seem as though he was paying attention in class. He was often found out anyway, with teachers confiscating, even ripping up, piles of his drawings.

The adult world looked joyless and brutish. Groening felt anticipatory nostalgia for childhood even as he was living it. “As a kid I decided I was never going to give up being a kid. The other kids were going to go on to become professional adults with briefcases. But I knew that I was doomed to making funny stories and drawing cartoons for the rest of my life, whether or not it was successful.”

Meanwhile, Groening had a love-hate relationship with television, watching it obsessively while always wishing it were better. He remembers being excited by the promise of the live-action Dennis the Menace television show, whose animated opening sequence depicted Dennis as a troublemaking tornado in the style of Looney Tunes’s Tasmanian Devil. But the character, in Groening’s view, turned out to be a wimp. Groening yearned to someday see a show where the tornado didn’t stop.

***

Coming out of a decade when cartoons had been explicitly, cynically manufactured to promote toys, the merchandising bonanza of The Simpsons, fueled by genuine popular demand, had the pervasive intensity of a biblical plague. In 1990, the show made $750 million through sales of merchandise and other products. At the height of Bartmania, as many as 1 million Bart Simpson shirts were selling a day. “As soon as it comes in, it sells off the shelves,” a JCPenney spokesperson told the New York Times.

Groening, who fielded upward of a hundred proposals a day from aspiring licensees in the first year of the show, was delighted with the improbably vast amount of Simpsons stuff out there. “He was in heaven playing the Simpsons pinball machine,” recalls Craig Bartlett, who married Lisa Groening and later created the animated series Hey Arnold! Groening says he decorated an entire guest room in his home exclusively with Simpsons-themed merchandise, cheerfully noting, “People would always only stay one night.”

Groening wasn’t the only one for whom the overwhelming demand for Simpsons merchandise presented an attractive and lucrative opportunity. Within weeks of the show’s premiere, off-brand Bart Simpson shirts sprang up for sale on sidewalk stands across the country: Teenage Mutant Ninja Simpson (“Kowabunga, dude!”), Air Simpson (“You can’t touch this!”), Rasta Bart (“Don’t have a cow, mon!”), Bart Simpson Public Enemy ("Fight the power!”), Punk Bart ("Anarchy in the USA!”), Skater Bart ("Eat my shorts!”), Bart Simpson Terminator ("Hasta la vista, man!”), Hip-Hop Bart ("Yo, homeboy!”), Gangsta Bart ("Don’t snitch, man!”), and more. Many of the shirts spoke to what one reporter called the “Afro-Americanization of Bart Simpson,” whom record-label president Bill Stephney characterized as “probably a lot more rebellious than a lot of the rappers today.”

“Even though he had a big piece of the merchandise, he still was really amused,” says Bartlett of Groening’s response to the burgeoning knockoff scene. “He took me down to the Venice boardwalk to buy ‘Simpsons go kinky reggae’ T-shirts. They were five dollars.” Groening was glad of the approval of television reviewers, but it was a source of joy that Bart resonated with these enterprising bootleggers. “My goal was to find a crossover Nelson Mandela, Bart Simpson T-shirt,” says Groening. (Mandela was released from prison earlier that year.) “And sure enough, it happened.”

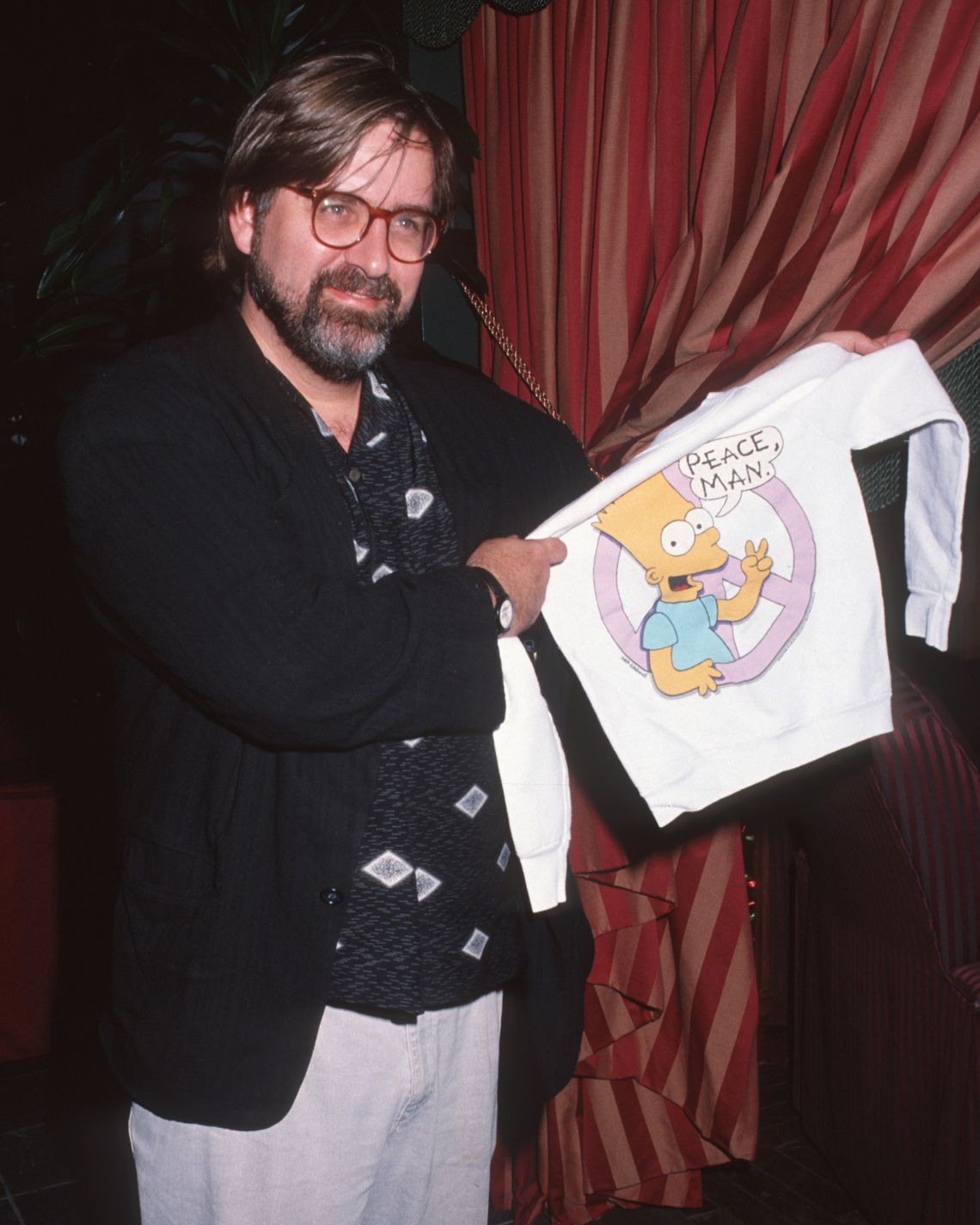

And yet, the most controversial Bart-related clothing turned out to be officially licensed. In April 1990, principal Bill Krumnow of Lutz Elementary School in Ballville Township, Ohio, banned students from wearing a shirt featuring Bart — poised to fire a loaded slingshot right at you, like a juvenile-delinquent Uncle Sam — bearing the label “Underachiever” along with Bart’s assured declaration: “and proud of it, man.”

Seemingly overnight, the “underachiever” shirt became the locus for the media-stoked controversy then swirling around the show. More school bans followed across the country; JCPenney stopped stocking the shirt in kids’ sizes. “To be proud of being an incompetent is a contradiction of what we stand for,” Krumnow told the Toledo Blade newspaper. “We feel like the Bart Simpson show does a lot of things that do not help students self-esteem,” principal Lonnie Watts of Taylor Mill Elementary School chimed in, “such as saying it’s okay to be stupid.”

While his fellow producers winced at the furor, Groening was pleased to have touched a nerve. “It’s always fun to tweak authority. And yeah, the fact that those T-shirts were banned at schools made me laugh.”

To Groening, the slogan “was about education. No child calls him or herself an ‘underachiever.’” Bart was reclaiming “underachiever,” a word first recorded in 1953 in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology, in a 100 percent cotton protest against the kind of education system that would dismissively label children with the term. “Perhaps I was called an underachiever myself,” says Groening. “And so the proper response is to say, ‘I am proud of it, then.’”

****

As Fox started airing reruns after the conclusion of season one in May 1990, the backlash and debate around the show only seemed to intensify. Barbara Bush called it “the dumbest thing I [have] ever seen.” Two Catholic nuns put out their own T-shirts featuring saints in the hopes they would “balance out Bart.” Touring a drug-rehabilitation center, former secretary of Education turned drug czar William Bennett expressed his disapproval after spotting a Bart Simpson poster on the wall: “You guys aren’t watching The Simpsons are you? That’s not going to help you any.”

The battle lines were drawn when Fox announced that in its second season, The Simpsons would move from 8 p.m. ET on Sunday night to 8 p.m. Thursday, going head to head with consistent ratings leader The Cosby Show on NBC. Naturally, the media hyped the event as Bart versus Bill, a showdown between one show’s wholesome family values and the other’s brash, boorish cynicism — the aspirational ’80s facing off against the anarchic ’90s. “TV should be moving in a direction from the Huxtables forward, not backward,” Cosby said when goaded for comment. “The mean-spirited and cruel think this [kind of programming] is ‘the edge,’ and their excuse is, ‘That’s the way people are today.’ But why should we be entertained by that?”

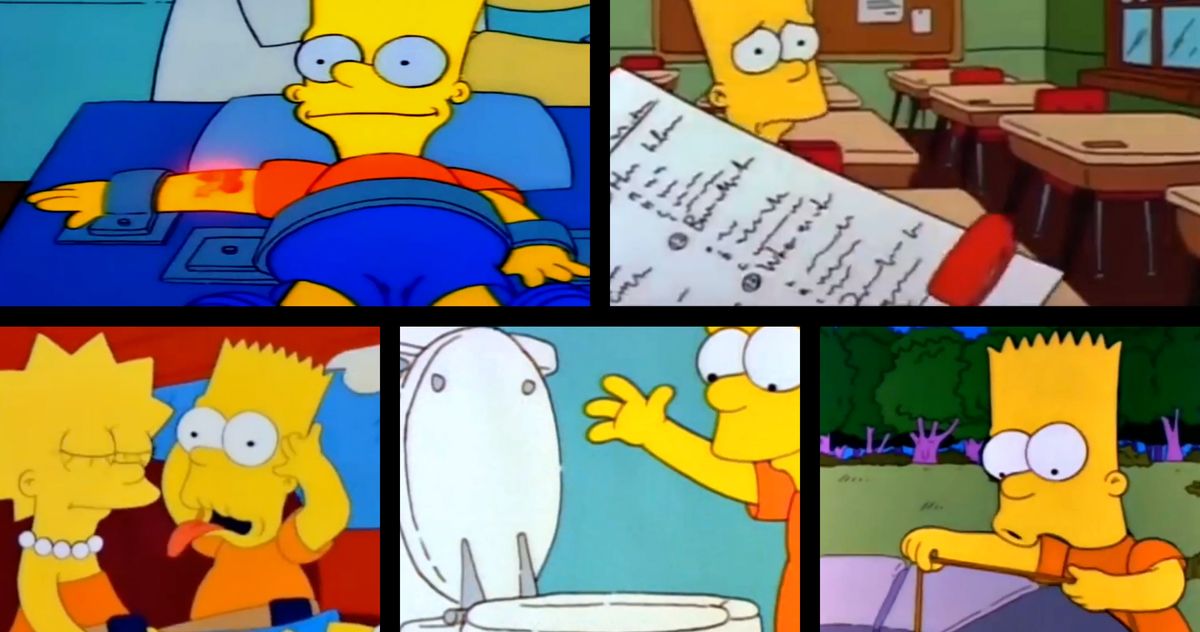

Some might have guessed that The Simpsons, for its October 1990 season-two premiere, would have launched into the battle all gags blazing, leaning harder into its edginess. Instead, viewers were treated to the most bighearted and affecting episode yet. In “Bart Gets an F,” Bart faces the prospect of repeating the fourth grade. He studies hard, earnestly prays for a miracle (which is promptly delivered), and breaks down, defeated, when he flunks again.

In one of the tenderest moments in the show to date, Bart falls asleep with his head in between the pages of a school book, having valiantly tried but failed to pull off a late-night cramming session. “The little tiger tries so hard. Why does he keep failing?” wonders Marge. “Just a little dim I guess,” Homer says, with real affection, hoisting his son off to bed. In short, he’s an underachiever — but doing his best.

But though the episode features the briefest of nods to the T-shirt controversy (“Bart is an underachiever,” a child psychologist tells Homer and Marge. “And yet he seems to be — how should I put this? — proud of it”), it wasn’t, its creators said, a reaction to it, or a conscious effort at rehabilitating Bart’s image. “It just seemed like a good idea for an episode,” animation director David Silverman says on the episode’s DVD commentary. Showrunner Al Jean agreed: “We never do anything for a reason.”

Nevertheless, viewers saw a softer, sweeter side of season one’s unapologetic hellion in “Bart Gets an F,” which Nielsen Media Research estimated was watched by 33.6 million people, making it the highest rated episode of the show to this day. When naming Bart its “Entertainer of the Year” for 1990, Entertainment Weekly pointed out how vividly, deeply human the character had become: “Bart has proved to be a rebel who’s also a good kid, a terror who’s easily terrorized, and a flake who astonishes us, and himself, with serious displays of fortitude.”

Still, people would go on being offended — or pretending to be offended. “I remember overhearing three mothers talking about this new show called The Simpsons that they didn’t want their kids to watch,” Nancy Cartwright told me. “I spoke up. I told them I honestly didn’t mind that they had their own opinions. I also asked if they ever watched the show all the way through. None of them had.”

As the ’90s progressed, The Simpsons’s less rosy, more complicated view of family rang truer than The Cosby Show. Even Bill Cosby would later admit to having developed a soft spot for Bart, sympathetically speculating that the kid was having a hard time at school “because he has a learning difference.” According to Groening, the co-existence of chaos with genuine familial bonds like those seen in “Bart Gets an F” is the key to the show’s appeal and longevity. “How do you deal with a group of people that you’re living with and love with all your heart but who drive you out of your mind? I think people can relate to that.”

***

Bartmania burned on, for a time. In 1991, “Do the Bartman” spent 11 weeks on Billboard’s “Hot 100 Airplay” chart, four Bart-centric video games were released, and Fox was forced to put a stop to the sale of bootleg “Nazi Bart” shirts. Bart Simpson’s Guide to Life and Bartman comics would soon be crammed into Bart Simpson backpacks. In 1993, the name “Bart Simpson” was still shorthand for miscreancy: a human-relations specialist in White Plains, New York, cited a rise in “irrelevant, confrontational, rebellious” behavior among secondary-school students, calling it the “Bart Simpson syndrome.”

But by then, the show’s center of gravity had shifted from Bart to Homer. “We did all the stories we could think of with Bart in season one and two,” said Reiss. “Whatever he is, he’s just a 10-year-old boy. He doesn’t live that full and rich a life.”

“The thing about Homer is there are more consequences to him messing up,” admits Groening. “Bart flunking a class is not quite as consequential as Homer causing a nuclear meltdown at work.”

Reiss realized that Bartmania was receding during one of his annual visits to the L.A. County Fair. “For a couple of years, every carnival attraction, the prize was a stuffed Bart Simpson. Then, around year three or four of the show, suddenly that was not the go-to prize. Then a few years after that, I suddenly see, oh, it’s Stewie and Brian from Family Guy.”

By 1994, The Simpsons had evolved out of its family sitcom foundations and more fully embraced its cartoon zaniness — basically, “Bart Gets an F” became “Bart Gets an Elephant.” Bart’s mischief was less likely to register as an influence on kids as the show around him became more unmoored from reality.

As the decade wore on, Fox executives fantasizing about another Bartmania-style phenomenon suggested that the writers introduce a new character who was “more Bart than Bart.” The Simpsons naturally responded with satire, introducing a sunglasses-wearing dog named Poochie to The Itchy & Scratchy Show. “It was our satirical comment on the idea of introducing a character to a sitcom late in its run in order to goose the ratings a little bit,” says Groening. “It was one of our best episodes. What’s funny is that we were being satirical and ironic and cynical and jaded, and people still come up to me and go, ‘I love Poochie! Bring back Poochie!’”

But there was no bringing back Bartmania. The show had already paved the way for other shows to push the boundaries of what was acceptable ever further, not just in animation (Beavis and Butt-head, South Park, Family Guy) but all over television: the shallow, self-centered protagonists of Seinfeld, the freak-show spectacle of The Jerry Springer Show, the skewering cynicism of The Daily Show. In a few short years, Bart’s antics felt as essentially innocent as those of Dennis the Menace had to Groening in the ’60s.

“The culture got so much more coarse,” says Groening. “They were sweeter times,” agrees Reiss, adding with audible satisfaction, “And I can’t help but think, Well, we were part of that coarsening.”

Today, the Bart Simpson “underachiever” shirt — shocking provocation and proof of the decline of civilization circa 1990 — is proudly enshrined in the Smithsonian collection.

“O C’mon All Ye Faithful,” a new double-episode holiday special, is now streaming on Disney+ in honor of the 35th anniversary of “Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire.”