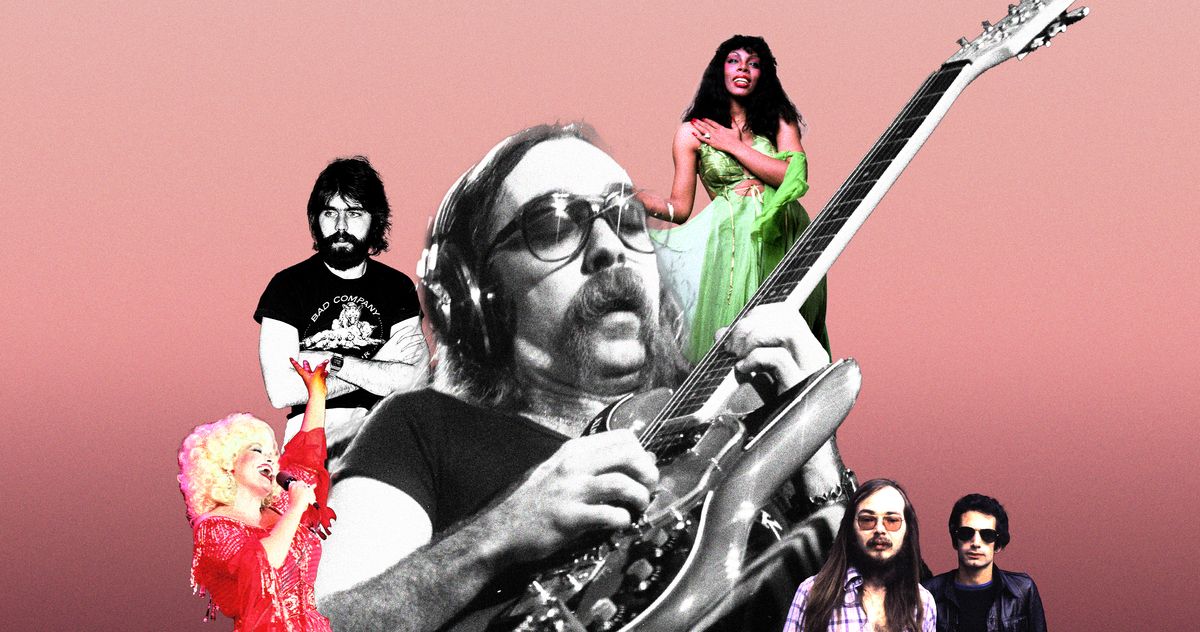

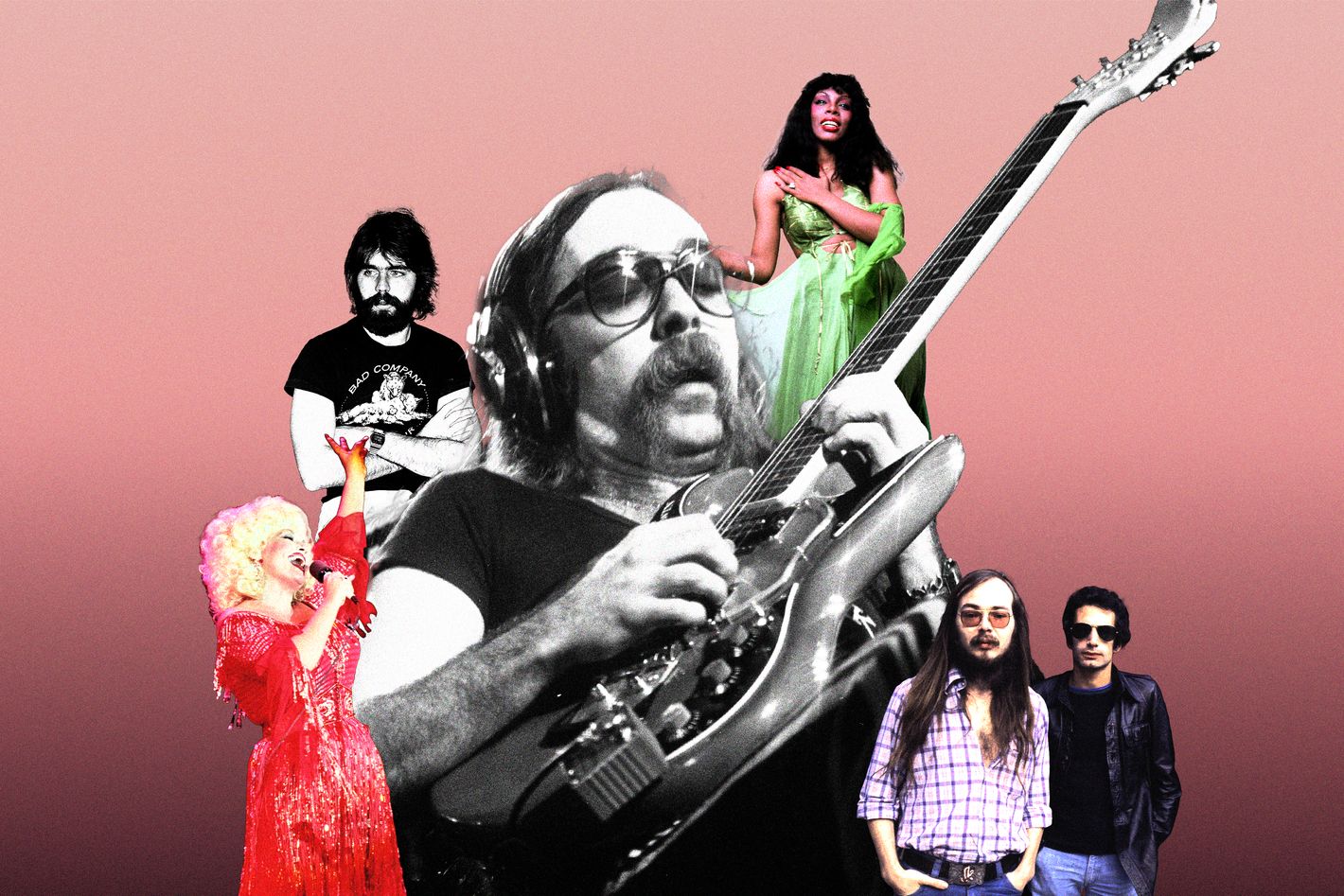

Jeff ‘Skunk’ Baxter Is the EMT of Guitarists

The Dan and Doobies member reveals his best throw-downs in the studio.

If we were to write a list called “Skunks, Ranked,” Jeff “Skunk” Baxter would triumph over his opponent, Pepé Le Pew, every single time. (Sorry Pepé, but you’re not a featured player on Pretzel Logic.) The guitarist, already a deity among Steely Dan and Doobie Brothers fans for formative stints with both bands, considers his life as a studio musician similar to to a craftsman who has the tools to construct whatever is needed. “You’re basically standing by and waiting for a call,” he explains. “It’s kind of like a combination of an EMT, a carpenter, and a number of other things to ultimately satisfy the artist. You park your ego at the door and get the job done.”

And Baxter always gets the job done. In addition to his work with the Dan and Doobies, he has marked his territory alongside the era’s top musicians, working with everyone from Rod Stewart to Glen Campbell to Cher. (He also, somehow, found the time to become a missile-defense expert, notching decades of consulting experience with the Pentagon and the Department of Defense.) Baxter’s recent record, Speed of Heat, was released back in 2022, and he embarked on this month’s Rock Legends Cruise. Before he set sail, Baxter — whose “Skunk” nickname origin is still rooted in mystery — looked back on what he considers to be his most rewarding sessions. “I take great pride and joy in helping other people fulfill their musical dreams,” he recalls with a smile. “It’s a great feeling.”

Steely Dan, “My Old School” (1973)

I was working in a shop repairing guitars, because I wasn’t making a whole lot of money at the time. I knew Steely Dan was going to do this song and I was just finishing building a Stratocaster. No dressings on it. It weighed about, I don’t know, ten pounds. It was a very heavy instrument. You know those things they put in front of the cars to keep them from rolling? The little cement things? I got the Stratocaster clamped down between two of those, put it in the back of the car, and drove it to the session. We didn’t do many takes, which was unusual, because a lot of times Donald Fagen and Walter Becker wanted to do it over and over and over and over. And there was no real direction, which was also unusual. At the time, Steely Dan was really more of a “band” and everyone contributed from their area of expertise. I just went for it and everybody seemed to like it.

Steely Dan, “East St. Louis Toodle-Oo” (1974)

The Steely Dan song I enjoyed recording the most was “East St. Louis Toodle-Oo,” which was a cover of a Duke Ellington song. We were all massive Duke Ellington fans. It was either Walter or Donald who said, “Let’s each pick one of the instruments from the original and substitute it with something else.” For example, Walter substituted the trumpet part with a wah-wah guitar. So I thought, “I’ll work with that trombone part.” The trombone has a slide so you can slide between notes. I had the idea to try it on pedal steel. Why the hell not? I worked on it for a good amount of time, and it was fun getting through that tunnel from one end to the other and playing that beautiful solo. I wanted the challenge and I was really satisfied.

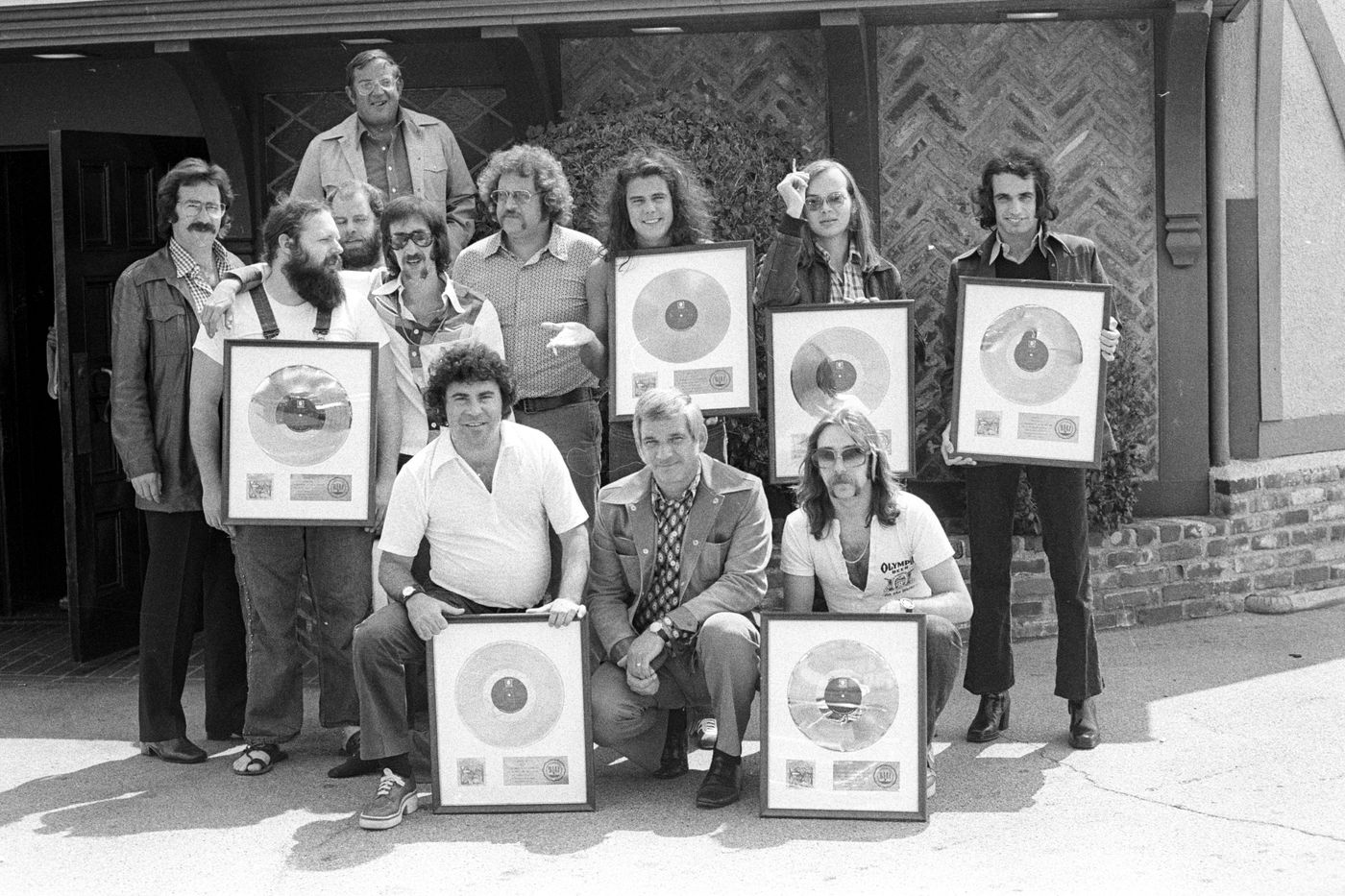

The Doobie Brothers, Livin’ on the Fault Line (1977)

I think Livin’ on the Fault Line was the best Doobie Brothers album. It was an exploratory record. It was stretching out everywhere. And while we were doing it, I thought, I’m a studio rat. Why don’t I suggest to the band that they work as a rhythm section for other artists? Just like Steve Lukather was doing with Toto. They all said, “Yeah, that’s a great idea.” So we started doing sessions for other people, such as Leo Sayer, Carly Simon, and Hoyt Axton.

There was something to me about this experience that was very constructive. A producer doesn’t care what band you’re in or how cool your shoes are. You show up at nine in the morning and you play it right or you’re fired. Those were the rules we would live by in the studio. I thought getting the guys in the Doobie Brothers into this concept would be a good thing. And they rose to the occasion beautifully. We had an excellent rhythm section. Not only were we great musicians, but because the band had played so much together, it was a great dynamic they brought that very few people did. Having had that experience paved the way for the massive success of the Minute by Minute album.

Donna Summer, “Hot Stuff” and “Bad Girls” (1979)

I got a call from Giorgio Moroder. He said, “I have this artist named Donna Summer.” I said, “Okay, what kind of music is it?” And he said, “Disco.” I’d done a million disco sessions. Some were interesting and some were less than interesting. So I told him, “I don’t know about this.” He said, “Listen, you can play whatever you want. I’m not going to write anything out.” How could I say no to a pitch like that?

But I realized, after I hung up the phone, that I was moving between houses and all my gear was still in a truck coming back from a tour. I didn’t have a single guitar. So I stopped off at Guitar Center in Hollywood. I used to go all the way to the backroom, find a guitar, smash it against the wall, and go to the manager and say, “Hey, this guitar is a mess. You need to sell it to me for parts.” He knew what was going on. He didn’t care. We were friends. So I walked in the store and said, “I need a guitar.” He laughed at me and said, “See that box out in the middle of the floor that says, ‘Buy me, $25’? It’s yours.” I pulled out this Burns Bison Jr. It had five regular tuning pegs and somebody replaced one of them with a Gibson tuning peg. It was kind of a mutt. I picked it up, plugged it in, and I went, “This is great.” I grabbed the guitar, literally no case, threw it in the back of the truck, stopped off to buy a six-pack of Bud Light, and then showed up at the studio. I still have that guitar, by the way.

The first thing they said was, “We have two songs for you right now.” They played me “Hot Stuff” and I thought it sounded great. I plugged into an amp, turned everything up to ten, said “roll tape,” and we did it in one take. I went back the next day with a prototype of the Roland Guitar Synthesizer. Those guys were all electronics freaks. They went crazy. They said, “We have to use this on something.” So I responded, “What do you want to do?” And then they played me “Bad Girls.” I knew I had to do a guitar synthesizer solo on “Bad Girls.” As far as I know, it’s the first recorded instance of ever using a guitar synth on a record. Donna was an absolutely wonderful human being and very engaged throughout the whole experience.

Dolly Parton, “9 to 5” (1980)

“9 to 5” was a bouncy and fun mixture of a lot of different feelings about music poured into one track, much of it based on everybody’s respect and love for Dolly Parton. They didn’t tell me what to play. They gave me the chords, but they were relying on the rhythm section to interpret what it could become. I had a lot of fun because I thought, I’m going to mix a little bit of Cajun with a little bit of chicken picking. I was sort of stirring the pot. Working for Dolly was an absolute joy. When we ran over the track, she was out in the studio singing, which I appreciated because if you don’t know where the vocal is going to fall, it’s a little more difficult to be sure what you’re playing is what the song needs. It wasn’t like you show up at the studio, cut the track, go home, and three days later the artist comes in and sings on the track. She was actively involved in everything — which she often doesn’t get enough credit for — and it made a big difference.

On being paid not to play

Gary Katz was, famously, the producer for Steely Dan. It opened up a lot of opportunities for him to produce other acts. He called me one evening and said, “I’ve just finished this album with a very talented singer” — I won’t name who it is — “and I need you to come in and listen to everything and tell me what it needs.” So I went in a couple of days later and everything was all set up. I probably hauled in 20 guitars and six different amplifiers — all the stuff you bring because you never know what they’re going to ask for. So Gary said, “Sit down and have a listen.” I listened to the record top to bottom. I turned to him and said, “It doesn’t need anything. It’s just perfect.” And Gary turned to me and said, “That’s why I pay you triple scale.” There’s something to be said for what you don’t play.

More From The 'In Session' Series