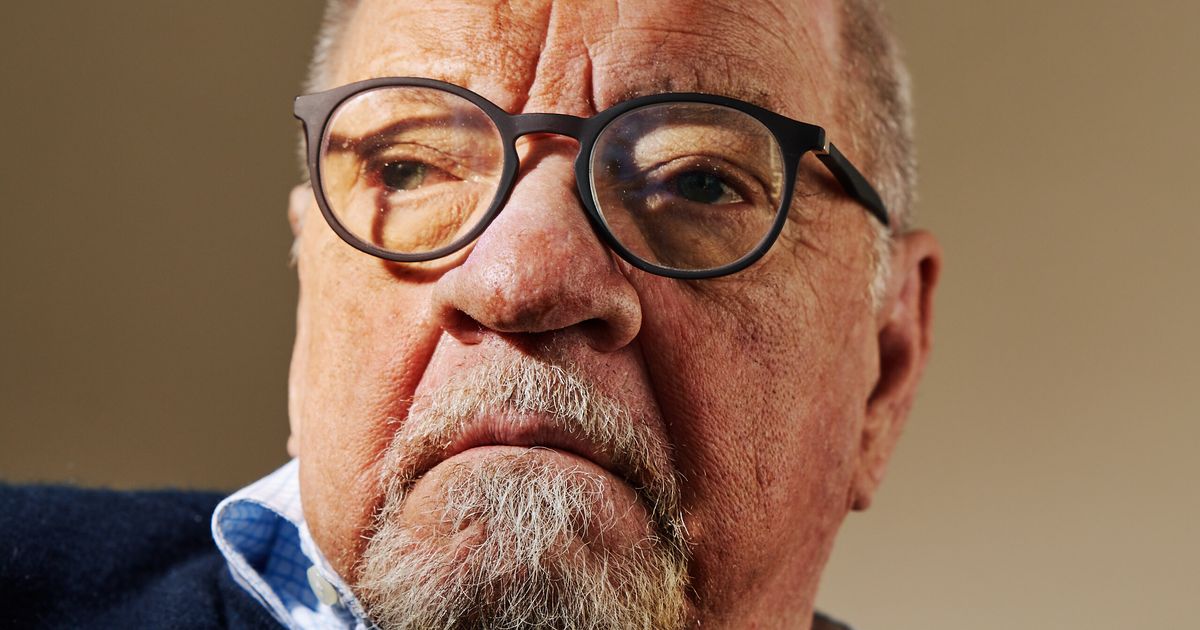

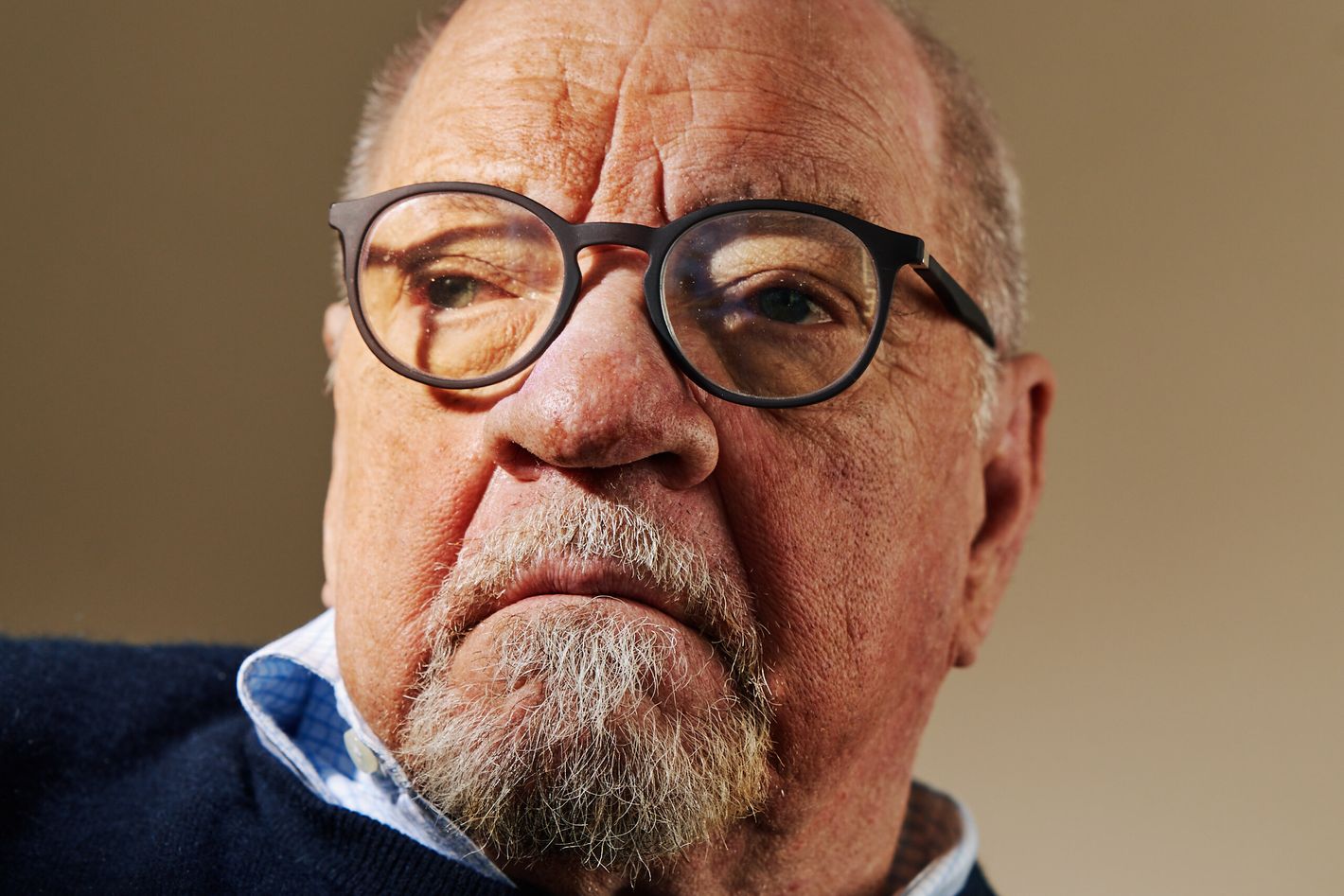

Paul Schrader Thought He Was Dying. So He Made a Movie About It.

“I actually thought when I was making it, Okay, this is the last one. It’s a good last one.”

A couple of years ago, Paul Schrader was convinced he was dying. He had just finished his 2022 film Master Gardener and was suffering from a variety of ailments that convinced him the end was near. He did get better, but that experience, combined with the death of his friend, the author Russell Banks, convinced the director to make his latest, Oh, Canada, an adaptation of Banks’s penultimate novel, Foregone. The film, structured around a final, confessional interview given by a dying documentarian (played by Richard Gere) about his life and career, has a funereal mood but a lively cadence. It’s a nonlinear dream loom about death and guilt and lies and disappointment — classic Schraderian themes — but it’s also light on its feet stylistically.

That’s sort of what talking to Schrader can be like. He loves discussing serious, existential subjects, but he always seems to do it with a chuckle. We meet in one of the well-appointed restaurants of Coterie Hudson Yards, the high-end senior living facility Schrader moved into in 2023 (both to make his life easier and to be closer to his wife, the actress Mary Beth Hurt, who is in a memory unit elsewhere in the same building). The day before, part of the complex caught fire — which Schrader, of course, posted about on Facebook — and during our conversation the phone rings a couple of times from well-wishers checking in to make sure he’s okay. For Oh, Canada’s opening, he even hosted a screening of the film for some of his fellow residents. (Coterie has a screening room that might put some Manhattan venues to shame. On the day of our interview, Schrader smiles and points to a schedule showing that, after the watercolor workshop and the mahjong club, they’ll be screening Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia.) Through it all, Schrader continues to work at a furious pace. As he discusses his reunion with Gere (whom he directed in 1980’s American Gigolo, one of the actor’s iconic roles), the challenges of making Oh, Canada, and all the ways that the film industry has changed, he can’t help but talk about the projects he’s working on now.

How did you wind up reuniting with Richard Gere for Oh, Canada?

I had decided to do a film for the book after the author, Russell Banks, got sick. Any number of actors could knock this out of the park, but you’ve seen them do it. Anthony Hopkins or Ed Harris, Tommy Lee Jones, Jonathan Pryce, you can close your eyes and see exactly the movie you’re going to get. I raise independent money on these films, so in order to get distribution, I have to sell them at the film festivals. You need a hook, to catch people’s attention. I was thinking, Richard’s never played old. That’s an interesting concept. I think people would be interested in that, and it would be good for him, too. So I asked him the three questions I ask every time I send a script: “(1) Are you available this year? (2) Will I get an answer in a week? (3) Do you understand my financial parameters?” And if I don’t get three yeses, I don’t send a script. I contacted De Niro, and he said, “I’ll say yes to the first two but not the third.” So I never sent him a script. You can waste a lot of time sending scripts to actors who are never going to do it. Once, we were at the Indie Spirit Awards, where Ethan Hawke was getting something — and Richard asked me, “How did you get him to do so little?” And after he agreed to do Oh, Canada, I reminded him of that conversation. I said, “You’re going to find out now.” Particularly well-known actors, they get a set of mannerisms and they fall into them, and most directors encourage that. I knew all of Richard’s mannerisms, down to his shoulders, with his neck and his cheeks, his hips, his feet.

You probably helped create some of those mannerisms with American Gigolo.

Yeah. And so just the code language, whenever I saw him do his mannerisms, I’d always say, “Richard, take it inside.” Meaning I don’t want to see what you’re expressing, don’t try to show it on your surface. He very quickly understood that was the instruction. You would have to do that maybe once a day, maybe every other day.

He’s always been such a physical actor.

Yeah, the walk, the strut, the swagger …

But now, you’ve put him on a deathbed, which must’ve been a challenge for him.

It was a good challenge. And he welcomed it, because people were getting a hermetic idea of what a Richard Gere role was. The buzz factor had gone down. So him playing aged and infirm — there’s going to be a buzz. In fact, it was harder to make him look 80 than it was to make him look 40! That had to do with the color of his skin. Tan as a mailman! He said to me, “I’m always the reddest person onscreen.” Once I realized that, you take the red out of his face, then you can make him look unhealthy.

He hasn’t really stopped working, but it felt like I hadn’t seen him in anything in a while.

I think he had resisted doing longform. I remember one day on the set, he said to me, “This is really fun. I forgot how much I liked it.” And I realized that he hadn’t been working that much. Soon afterward, he accepted a ten-episode thing.

This is a problem many actors run into after a certain age. For example, until he reunited with Scorsese, it felt like De Niro had become kind of a punch line — because people joked about how he was always making trashy movies and comedies and stuff like that. But after a certain age, the great roles really start to dry up. Yet you have to keep working.

Also you had to deal with the devil. The devil was named Mike Ovitz. Mike had a scheme. He would find something that an actor or a client liked. Marty was good at preservations. And somebody else was paintings. With Bobby, it was real estate. Ovitz would encourage them, give them hints, give them very good suggestions, and they would go for it but then they needed money. What do you do when you need money? You work for it. “Oh my God, I just got the film for you. It’s not a great film, but it’s a great paycheck.” That’s how Mike would trap these guys into doing it. He tried to sign me, but I didn’t go for it.

How would he have trapped you, do you think?

I don’t know where he would’ve found my point of weakness. I had a meeting with him and then something like three days later, he invited me to sit with him at a Lakers game. And I said to his office, “I just met with him. I don’t want to be with him again.” They said, “Mike is asking you to sit with him at a Lakers game.” “Yeah, no, but I don’t feel like it.” That was the end of that.

I enjoyed how you used Phosphorescent’s songs in Oh, Canada. It reminded me of the way you used the Michael Been songs in Light Sleeper.

The song cycle. For that, you need four or five songs written and performed by the same artist that form an additional narrative arc. You have your plot arc, your voice-over arc, your dialogue arc and then you have your music arc. Originally, I proposed it to Bruce Springsteen. He said, “That’s an interesting idea. Why don’t you send me the script?” Then I hung up the phone and I thought, Wait a second. I want an anti-anthem of the Canadian national anthem in the film. Bruce cannot do an anti-anthem. Even if he does “Happy Birthday,” it will be an anthem. I got back in touch with him, and I said, “I think it’s a bad idea to ask you to do an anti-anthem.” So then I thought of Phosphorescent, who I’ve liked for quite a while and saw a few years ago.

Having Bruce Springsteen of all people singing “O Canada” would’ve been pretty cool, though.

But it would’ve been an anthem. And what you have now at the end is this dirge and this wavering voice. It would’ve been cool, but I don’t think it would’ve been right for the film.

When you showed Oh, Canada at the New York Film Festival, you got climate protesters.

Oh, yeah. A very brief interruption.

At the time of First Reformed, you yourself were very eloquent and urgent about climate collapse.

And the issue has not ameliorated or gone away. I’m fond of this Al Franken quote, where he’s talking about the new horses of the apocalypse — climate change, thermonuclear war, global viruses, AI. And he said, “My fellow baby boomers will understand me when I say we got the last helicopter out of Saigon.” I think it does feel like we got whisked away. There’s an article in the front of the Times yesterday about the decrease in grandchildren. And my kids don’t have children. I don’t know if they believe in the future. I believe in the future. I don’t know if they do, and I don’t know if they have reason to.

Oh, Canada reminded me a little bit of Bertolucci’s The Conformist in the way that it jumps back and forth and goes deep within flashbacks, so that you’re almost lost in this maze. I know that’s an important film for you.

The Conformist for me is a lodestone. You’ll find something from The Conformist in everything I do because I think it’s a foundational film. But that idea of the flexible time frame, it’s getting very common. Last night, I was watching Lincoln Lawyer — the episodic, not the Matthew McConaughey one. There’s season three. You’re going to bring somebody to testify, and they bring them up to the stand, and they cut to the very first time that something happened in the past, and in the middle of something that’s happened in the past, you hear the lawyer ask a question and then it jumps again. It’s just lingua franca now.

My new approach then became to investors: "I’ll put you on a red carpet — Venice, Berlin, or Cannes — and I will not make you rich, but I think I’ll make you whole.”

That’s a bit of a departure for you, at least in your recent work. Generally, your movies tend to be fairly linear.

Yeah, I call them monoscopic. This is stereoscopic. It’s a mosaic of the book, mosaic structure, like Mishima. But when you do a complicated style, you have to try to make it simpler. So I have this situation, his last day, then I have his trip from Virginia to Canada, then I have other things that happened and then I have a little section about his son and each of them is in a different film ratio and color format. That’s to make it easier to watch. You can do that now in a film that’s digital, but you couldn’t do it with Mishima. When you have a 35-mm. print, you set the curtain, you’re stuck in your aspect ratio, whatever it is. Now, you can go wherever you want. You could do like Xavier Dolan did in Mommy, where you go from 1.33 aspect ratio to wide screen in the middle of a shot. Really, there are no rules anymore.

But the rules were never that ironclad, were they? You were in that first AFI Film Directing class, along with David Lynch and Terrence Malick and all these other people who became major names. You guys broke a ton of rules.

Well, that’s because of the fundamental shift in the industry. With studio control, they would decide your career for you. When Billy Wilder’s career was over, they phased him out. You knew your career was over when the phone didn’t ring. Now, your career is over when people don’t answer your phone, because you’re the one who’s making the call, not them. And if you can still put together a project at the age of 80, you can make it. But the change in the studios came around the summer of ’69 with Paint Your Wagon and Hello, Dolly!, two big, big 20th Century Fox films. They both were tepid, while Easy Rider, a nothing film, exploded. Well, the handwriting couldn’t be bigger on the wall. So there was a period there from about 1970 to ’79 where the studio executives were floundering. They knew that the old wheels weren’t working, but they didn’t understand how the new wheels worked. You could go in there and pitch them and they would be very receptive. I remember Francis Ford Coppola said to me, “You just walk in there and you say to them, ‘I know you only care about making money. I only care about making money. This is our lucky day. Let’s make some money together.’ And they’ll believe you because they want to believe you so much.” You’re telling them a story: “We’re going to do this kind of film. Let’s do The Strawberry Statement.” “Okay.” And I remember when it came to an end. Barry Diller, who had come up through ABC and was heading Paramount, had been very involved in market research at ABC. He brought over his head of market research, who used to be at an office way on the other end of the Paramount lot. Diller took that office and put it right outside his, so you had to go through market research to get to his office. So the message was absolutely clear: “We used to not know what we wanted. We know what we want now.”

Were you able to tell at the time that period was ending? You worked on Raging Bull with Scorsese, which comes out in 1980.

I did Cat People in 1982, and I wanted to do Light of Day. At that time, it was called Born in the USA with Bruce Springsteen. I couldn’t get Bruce into it, but I realized the atmosphere, the temperature in the room was going down, and I had this fantasy about going to Japan. So I thought, “Well, it’s maybe a good time to go down.” Mary Beth was pregnant, and Tom Luddy said, “Come to Japan while she’s pregnant. It’ll force everything into action because they’re dragging their feet here. If she comes over and she can’t go back, things will start to happen.” So we went over; my daughter was born there. I did Mishima.

I remember, when I made Light Sleeper, I showed it to Mike Medavoy, who used to be one of the machers. I forget what company he was with at the time. And Mike called me and said, “Oh, this is a really great film. I really loved it. But you understand, we don’t make this anymore.” That simple. We don’t make this film anymore. It was that cold.

Around then, you started doing more independent films. But you did sometimes go back into the studio fold.

Well, I got suckered into the Exorcist thing, because John Frankenheimer died, and he was originally scheduled to direct. I shouldn’t have done it, but it was a “go” film, everything, but it was not people that I should be working with and not people who really respected me. People I very quickly came not to respect myself. And so that was a mistake. And then I had this thing with Dying of the Light, which I raised the money independently for. But I was now raising money not from movie people but from equity people who didn’t watch movies — in fact, didn’t really care for movies that much. And I wanted to reshoot the ending of that. And one of the guys said, “Look, you’ve delivered a Nicolas Cage action film, a prescribed length, five action scenes. We can make 17 percent on our investment. Why should we reshoot anything?” They were right by that logic, because he wasn’t making a movie, he was making an investment.

That’s when I realized that I needed final cut. Before that, you had kind of a de facto final cut. It would get changed: You’d preview the film and sometimes it would get a little better, sometimes it would not get better, but it was still an agreement between the filmmakers in the executive offices and the filmmakers on the set. Well, when there are no longer filmmakers in the executive offices, you’ve got to have final cut, because otherwise you have no protection. You’re not going to talk sense into these people because they’re not interested in sense other than dollars and cents.

So then I switched to final cut, and I used Nic to get me there. I had it of course in The Canyons because we paid for the film, but after that debacle with Dying of the Light, I got the script to Dog Eat Dog, and I said, “I think I can get Nic to do this.” I went to Nic, and I said, “I want to do this with you, but because of our past experience, you have to say that you will only do it with me if I get final cut.” He said, “Okay.” Bingo, I had final cut. And then once you have it, it’s harder for them to take it away from you.

But then you do First Reformed, which inaugurates this period where suddenly your work gains new traction, even and maybe especially with younger audiences.

Well, that’s the final part for you. First Reformed is a script that I had often thought about writing, a religious script. My Winter Light, my Diary of a Country Priest. I never wrote it because I knew I couldn’t sell it. And I knew it would be a stain against my ability to put things together because it would reinforce the prejudice that I’m elitist and not a populist. And I would not have written that script if (1) I didn’t have final cut and (2) if the technology did not permit me. When I started making movies, the average shooting days were 40, 42; now they’re 20. My last film was 17. And you get as much raw material in four weeks as you used to get in eight, just because everything’s faster. Because of that, I could switch and do things that I couldn’t do before. Oh, Canada was relatively easy to put together. A few name actors. And then get that budget way down there. When you write the script, bear in mind the cost of every scene, the value of every scene, so that you can walk in the room with a $4 million budget when they think they’re going to get an $8 million budget. And they probably are; in other hands, it might be an $8 million film. So then you can finance that film because you can make investors whole.

So my new approach then became to investors: “I’m going to make you a film that when you’re at a dinner party and you bring it up, people will be impressed. I’ll put you on a red carpet — Venice, Berlin, or Cannes — and I will not make you rich, but I think I’ll make you whole. You’re making a lot of money right now, making diapers or diaphragms or whatever. Wouldn’t you rather try this?” And those guys, they do like to dress up in the tuxedos, and this is the only chance in their life they get to walk up the steps at Cannes. So that’s their payday. And if they could get made whole, then that’s all they really care about.

You’ve often talked about the way that you create your scripts: “The problem is loneliness, and the metaphor is the taxi cab. The problem is loss of faith, and the metaphor is climate collapse. The problem is midlife crisis, and the metaphor is a drug dealer.” So there’s a problem and then there’s a metaphor.

And then there’s a plot.

But you would always add, “Well, I’m not these people. I’m not a drug dealer. I’m not a gambler.” With Oh, Canada, it’s interesting because I feel like the metaphor is filmmaking, and you are a filmmaker.

The character in Russell’s book wants to be a novelist and ends up as a documentary filmmaker. So that was the distance Russell put between him and the character, which was quite autobiographical. If you read his autobiography, you’ll see a lot of the same incidents. So if I had done this from scratch, I probably would’ve made him a painter, just to get a little bit of distance. But I’ve also never been a documentary filmmaker. If it had been about a screenwriter, I probably would’ve changed it.

Did Russell know he was sick when he wrote the book?

No, he wrote it when he was healthy. And he sent it to me. He called it his Ivan Ilyich. In fact, he had Ivan Ilyich on the desk beside him. So it became my Ivan Ilyich. I would spend a week during the summer with him. Because he used to have a lot of smart guests over there, Paul Groves, William Kennedy, and all of that. About two years ago, I called him up and said, “What’s a good week this year?” And he said, “Not this year. I’ve got cancer, I’m taking chemo.” And I knew he had written this book about the death process. I said, “Well, I should read that.” I was thinking of doing something else, and I said, “This is what I should be doing. I should be doing a movie about dying.” Because you can’t do a dying movie on your deathbed. You have to be pretty healthy to make any movie. It’s not like writing your last poem as you die. So I thought, If you’re going to do a dying movie, you better hurry up. I’d had some health difficulties with COVID, bronchial pneumonia, in and out of the hospital. I actually thought when I was making it, Okay, this is the last one. It’s a good last one. But then I bounced back from that. So now I’m trying to figure out how to make the last, last one. And maybe after that will be the last, last, last one. But when I contacted Russell, he said, “If you do it, please give it the title I had, Oh, Canada.” He had been kept from using that title.

And with that title, the idea of Canada becomes much more prominent in the film.

Yeah, well, it becomes a metaphor for irresponsibility, escape, and death.

We were guilty. We were unsaved. Once you have that in the back of your head, it’s always working its way through.

You mentioned that First Reformed was a film you’d thought about writing for years but were almost afraid to. With certain filmmakers, making the film that they were always running away from almost liberates them and they enter into a renaissance period.

Yeah, because you really have nothing to lose anymore. So much of your career, you’re working on the stepping stone of a project. “How will this film get me to a next film, a bigger film?” But when you hit a certain plateau, you say, “It’s not going to get any better than this. Enjoy this one. If I’m fortunate, I’ll make another one just like it.” And I’m writing another one of those right now. I wrote a very nice scene yesterday.

This one is called The Basics of Philosophy. I tried to find out a new way to do the journal concept, because it’s getting a little too predictable. So this is a philosophy professor who’s already written a textbook, and now he’s writing a book on Spinoza. And the narration, the voice-over, is from his book on Spinoza. I’m in touch with Spinoza scholars. I did the equivalent of a grad-school course on Spinoza in a week. Now, I have to find his diary voice. I think that’ll be more effective than having it be a straight diary. I just asked Spinoza scholars yesterday, “If you were to meet Spinoza today — and he’s really one of the foremost figures of the Enlightenment, of secular pantheism — if you were to meet Spinoza today, knowing 21st-century problems, what would you ask him?”

Getting back to this idea of why your films resonate so much now with today’s viewers. I read an interview in which you talked about a time when you were on the phone with your dad an›d you discovered that he was part of a local group protesting the Last Temptation of Christ. But when you related this story, you also said that you actually had a lot of admiration for him for walking the line, sticking to his beliefs despite the fact that his son had written the movie.

Did I tell you about the shrink-wrapped VHS tapes? Later, I discovered that he’d owned videos of all my films and my brother’s films. Still in their shrink-wrap. “I’ve bought the movies. I never looked at them.”

But I think there’s something there that relates to your work and the things you’re drawn to. And now, with generations that live in public, with social media and everything, everybody I think really relates to this idea of trying to live up to a professed ideal. The struggle to feel like you have a code, or to present yourself as having a code. That’s what Oh, Canada seems to be about, too.

Well, I’ve said this before, the computer gets programmed early. Freud said it was five years. I think it’s more eight or nine years. But anyway, that software gets loaded in. And then your stuff, you’ve got to run it the rest of your life. And my software was full of guilt and predestination, original sin and predestination, and we were guilty. We were unsaved. And anybody can identify with that because it’s true. Once you have that in the back of your head, it’s always working its way through.

And not only are you not living up to your ideals, everybody can see you not living up to your ideals.

In my case, it’s codified, because my mother used to say, “My best works are filthy rags in the sight of the Lord.” Well, that doesn’t leave a lot of room for social improvement.

Oh, Canada is all about this to me, because he has this guilt, this sense that he hasn’t lived up to the image that he’s put forth of himself. But when we find out what it is he feels this guilt over, it doesn’t even feel like that traumatic a thing.

It’s all a lie. It’s all a career lie. I did an interview with Richard this morning. He said in the interview, “When he admits his greatest sin, I’m not sure that he’s telling the truth even then.”

It’s almost like we need guilt. We try to shed ourselves of it, but without guilt, we’re not human.

Our bodies are the fire, and guilt is the coal.

Related